Canadians from all parts of the political spectrum are deeply concerned by the rise of polarization, extremism, and misinformation in Canada’s democracy.

Even folks who lean to the political right acknowledge that Pierre Poilievre won the Conservative race by making himself the hero of those who oppose vaccines and mandates, believe conspiracy theories, and are angry to the point of rage at Justin Trudeau.

In the words of former BC Premier Christy Clark:

“We’re watching the Conservative Party of Canada make its race for the extremes to play to the very edges of the political divide.”

Danger ahead?

In a nation with first past the post, the direct appeals Pierre Poilievre made to those on the extremes should scare the heck out of us.

A look at our neighbour to the south gives us an idea of what could be coming: a sharply divided nation where “the truth” splits along partisan lines. After all, a good portion of Poilievre’s voting base overlaps with the 16% of Canadians who believe the American election was stolen from Donald Trump.

“Rage-farming” by the political right is an increasingly common practice, yielding results like what Chrystia Freeland experienced in Grande Prairie recently, and leading many MPs to fear for their safety.

Conservative MP and leadership candidate Scott Aitchison recently warned:

“Every day, I get emails from people who are incredibly angry & paranoid. They think we should put Trudeau on trial for crimes against humanity. They claim vaccines are killing millions and compare it to the Holocaust. This is what fear, anger, & misinformation are doing to Canada.”

Our first past the post system has enabled a politician who fuels partisan hatred and panders to those spreading dangerous conspiracy theories to capture the leadership of a big tent party—and he may well be on his way to the Prime Minister’s office.

Under winner-take-all voting, a party with little more than one third of the popular vote can be handed 100% of the power.

Poilievre’s team reports that they signed up about 300,000 new members. He won the Conservative leadership with about the same number of votes. Those individuals are now highly motivated to amplify the messages that appealed to them the most.

Justin Ling’s assessment of Poilievre’s landslide victory in the Conservative leadership race was pointed and illuminating:

Those who maintain that a leader who caters to the extremes could never win a national election are quick to forget how almost every reputable US pollster and media guru in 2016 didn’t see Donald Trump’s victory coming.

Democracy in the United States is on a precipice right now, and no-one knows how to turn back the clock.

Proportional representation: extreme views get fair representation but not disproportionate power

Politicians who cling to first past the post in Canada think that denying some voters fair representation is a viable strategy to stomp out extremism.

The Freedom Convoy and the recent Conservative Party leadership campaign should make it obvious that those with grievances—including those denied fair representation by the voting system―will find a way to be heard. First past the post enables their impact to vastly exceed the size of their following.

When it comes to extremism, winner-take-all voting is like pouring gas on a fire.

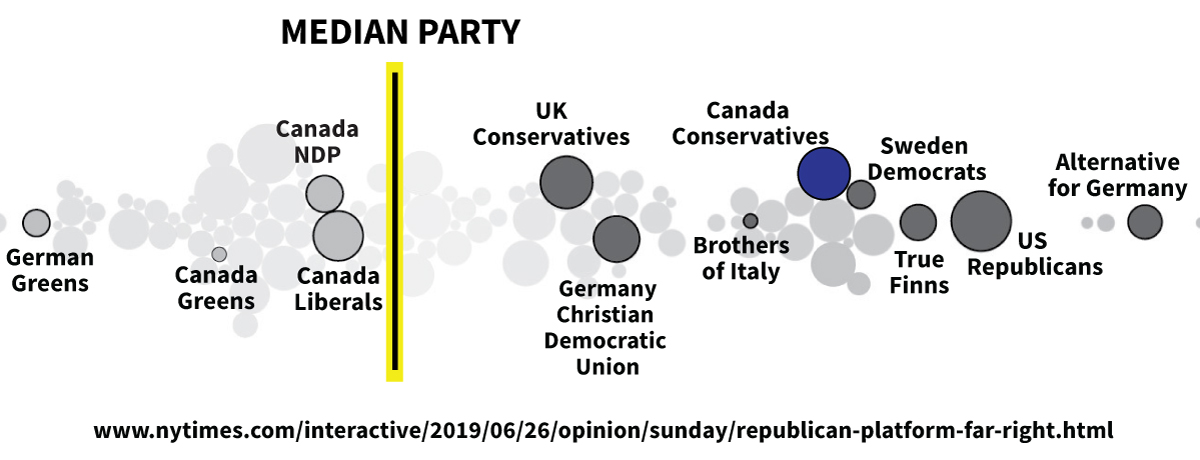

Comparing our Conservative Party to other right wing parties around the world provides some perspective. The Manifesto Project analyzed the 2017 platforms of parties in over 50 countries, placing them on the left/right spectrum. In 2015, Canada’s Conservative Party was in virtually the same spot as the far-right Sweden Democrats:

It’s safe to say that under Pierre Poilievre, Canada’s Conservatives are moving even farther to the right.

In countries with proportional representation, those with views outside the mainstream are more likely to form their own political party. With PR, almost every vote counts.

Unlike in Canada, voters for a party with extreme views will receive representation proportional to their popular support. Almost no-one is shut out.

However, proportional representation ensures that the minority doesn’t receive a majority of the power.

In many cases, if a party’s positions are too extreme, other parties will refuse to work with them.

When small far-right parties seek to transition from protest parties to being junior partners in governing coalitions, they usually have to moderate their brand and policies to be successful. This might involve dropping fringe policy positions, or removing members of their party.

Even as part of a governing coalition, parties that lean to the extremes don’t have the power to implement wildly unpopular ideas.

With proportional representation, a party with extreme views would never be able to govern alone and unilaterally decide policy for the country.

Proportional representation means cooperation and compromise.

Proportional representation: an evidence-based reform to tackle polarization while strengthening democracy

The Economist Intelligence Unit warned earlier this year that Canadian democracy is increasingly vulnerable:

“New survey data show a worrying trend of disaffection among Canada’s citizens with traditional democratic institutions and increased levels of support for non-democratic alternatives, such as rule by experts or the military. …

Canada’s worsening score on the Democracy Index raises questions about whether it might begin to suffer from some of the same afflictions as its US neighbour, such as extremely low levels of public trust in political parties and government institutions.”

It’s time to take off the blinders of Canadian exceptionalism and step up to the challenge of fixing our democracy.

Comparative research on electoral systems has shown that:

- Voters in countries with winner-take-all voting systems perceive their country’s political parties to be further not only from one another, but also from themselves. In other words, winner-take-all systems are more polarized.

Rodden (2018) concludes: “Proportional representation brings a powerful advantage: it can allow the political system to absorb the rise of new issue dimensions, from environmentalism to women’s rights to nativism, without the issue-bundling that facilitates all-encompassing American-style polarization.” - Proportional representation helps reduce feelings of partisan hostility.

Horne, Adams and Gidron (2022) found that people in countries with PR felt warmer towards any parties that had been in a coalition government with their preferred party anytime over the previous 15 years. This warmer feeling remained even if the parties that had been in a coalition together were ideologically far apart. - The language in Parliament is more civil.

Nemoto and Pinto (2019) studied the nature of political discourse in the New Zealand Parliament before and after proportional representation was adopted in 1996. Analyzing 821,442 parliamentary speeches by MPs from 1987 to 2016, they found a marked decrease in anger and hostility in MP’s speeches overall after 1996, most significantly in the tone of ruling party MPs towards smaller parties who might one day be coalition partners with them.

Amidst a sea of democratic decline and the rise of authoritarianism around the world, a 2020 Cambridge University study found that the seven countries that defied the trend all used proportional representation.

As OpenMedia founder Steven Anderson recently wrote:

“We need a real dialogue about how we can come together to turn the tide on the democratic decline we’re facing.

The time is now. If our democratic system isn’t functioning, we’ll be hard-pressed to address urgent issues like climate change, racial and other oppressions, or the cost of living crisis.

Whatever issue or cause you care about most, democratic renewal should be second on your list.”

Actually, it should be first. Everything else could depend on it.