Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre’s relentless campaign to “axe the tax” foreshadows what could be the biggest climate policy reversal ever in the OECD.

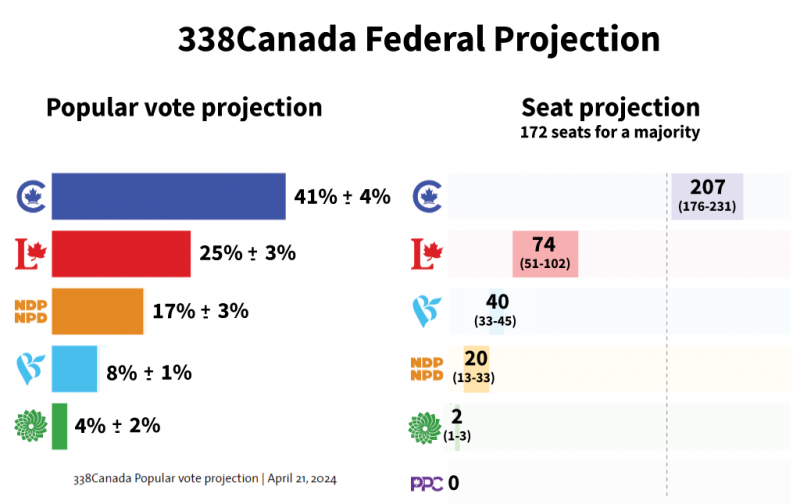

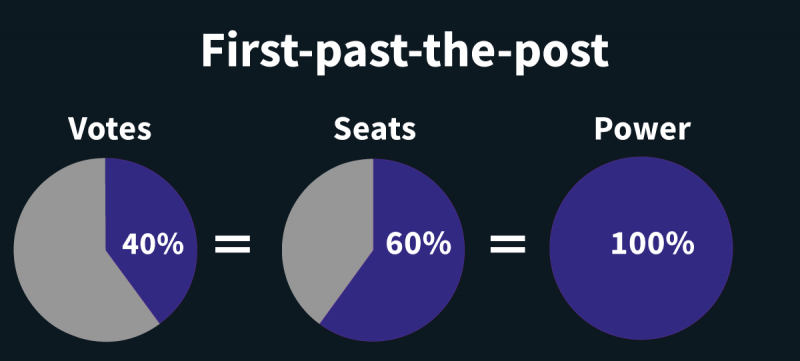

Projections show the Conservatives on track to win a crushing “majority” government with just 40% of the popular vote, thanks to the seat bonus provided by first-past-the-post.

Poilievre has been crystal clear in his ruthless, laser-focused attack: he will use a so-called mandate from a minority of voters in our first-past-the-post system to tear up Canada’s national carbon tax.

After seven years of having a carbon tax in place, businesses, consumers and even energy utilities have planned—and invested—accordingly. The potential impact, both financial and environmental, of reversing this key climate policy is unprecedented in the OECD.

Policy lurch is always expensive, but this particular reversal would cost even more than usual. As protection for their investment in reducing GHGs, some businesses have signed “carbon contracts” with the government, transferring potentially billions of dollars of risk to taxpayers.

Why does the carbon tax matter to meeting Canada’s climate targets?

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a global challenge, where success depends on countries implementing increasingly ambitious measures to “bend the curve.” Failing this, scientists have been brutally clear: the less we do, the more we’ll all suffer later from devastating and irreversible consequences.

Decades of research by (non-partisan) scientists and economists have shown that carbon taxation is one of the most effective (and least costly) tools to bring down emissions and shift economies away from reliance on highly polluting fossil fuels.

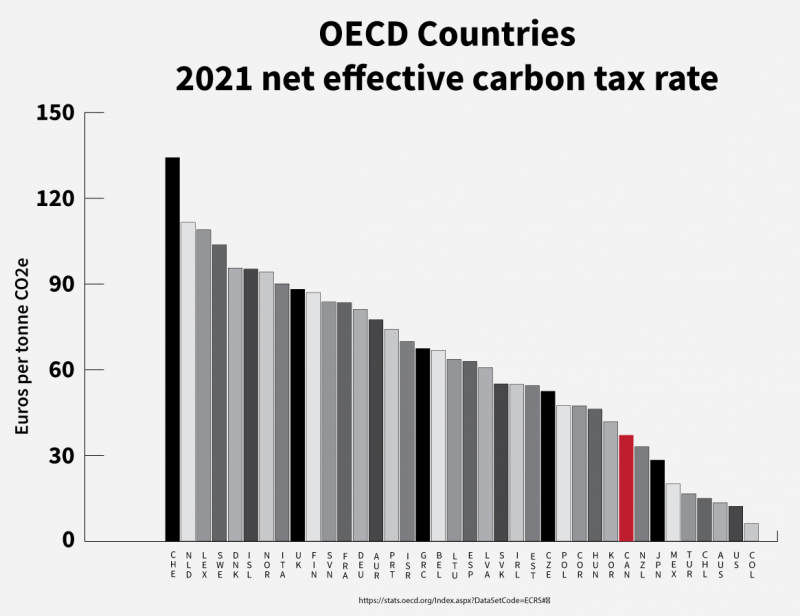

That’s why almost every country in the OECD has made carbon taxation a central part of their climate policy:

While Canada was comparatively late to the party at the federal level, we finally got started in 2018 with a comprehensive federal climate plan to reduce our emissions by 2030, in line with the commitments we made to the international community as part of the 2015 Paris Accord. Despite its flaws, Canada’s current plan represents the first serious effort to make progress, a marked departure from the decades of empty promises and no action.

The carbon tax was projected to account for up to one third of Canada’s emission reductions by 2030.

Let’s be clear: a carbon tax is generally recognized as an effective and efficient mechanism for reducing emissions, but it is only one option among many. Which mechanism to use is indeed a political choice. Other valid options include a partial zero-emission vehicle standard, a low-carbon fuel standard and sector-specific performance standards for industry that set declining percentage emissions intensities. Economists tell us that the alternatives would be more intrusive and would cost taxpayers more, especially in light of the rebates provided to consumers by the federal government.

The removal of the carbon tax would constitute a serious and costly policy lurch, but the greater risk is that Canada would be left with no serious climate plan at all.

At present, none of the politicians calling to scrap the carbon tax have proposed any viable plan to make up the 30% of emissions reductions the carbon tax is projected to deliver.

It’s not just the carbon tax that will be relegated to the dustbin if the government changes hands—other elements of the national climate plan to reduce emissions, including the Clean Fuel regulations, and the transition to electric vehicles are also the chopping block. These changes can be expected to trigger further knock-on effects at other regulatory levels.

If Canada ditches the national carbon tax in 2025, not only will it be extremely difficult for us to meet our international obligations to climate action under the Paris Accord, it will make Canada an outlier among our OECD peers

In fact, it’s not clear if a Conservative government would even keep Canada in the Paris Agreement. Withdrawing from the accord would immediately re-establish our country as an international climate pariah, a reputation we’ve only recently begun to shake.

Top of mind election priorities fluctuate, but a strong majority of Canadians back effective climate action

Policies that directly and immediately impact our personal security will naturally dominate conversations at the door as we head toward an election. Recent polling shows that the rising cost of living is the number one concern of Canadians. The housing crisis, as it continues to escalate and cause immediate pain to many, is another top of mind issue. Healthcare and the economy round out the top four.

In a reversal of previous trends, older Canadians—who are more likely to be financially secure—prioritize climate action more highly than millennials.

But while anxiety about pocketbook issues has knocked climate change down the list of priorities, that doesn’t mean the majority of voters want to see Canada renege on our climate commitments nor erase the progress we’ve made. Inundated by heat waves, wildfires and other extreme weather events, most Canadians know that neglecting serious climate action means putting our long-term well-being and security at risk.

A majority of Canadians are concerned about climate change and remain supportive of strong climate action from the federal government.

If Canadians still care about climate change, why are we heading for a wild swing on climate policy?

Winner-take-all voting is squarely to blame for the depth of the mess

Climate change solutions have always been a bad fit for the short-term, short-sighted nature of electoral politics.

Effective, long-term solutions require thinking well beyond the life of any government. Their implementation does not produce dramatic, immediate improvements for which politicians will be rewarded at the ballot box.

Worse, the politicians in office today will be collecting their pensions, or may not even be alive, when the most devastating consequences of their climate decisions come home to roost.

While these political realities are true in every country, the perverse incentives of winner-take-all voting exacerbate the problem.

Any government could prioritize urgent action on the housing and healthcare crises, while at the same time keeping Canada on track with the plan to meet our international climate commitments. We can walk and chew gum at the same time. That’s what most voters want.

If that’s the case, why has an “axe the tax” (and the climate plan) campaign become a mainstream, powerful force in Canada?

The answer is obvious: Winner-take-all politics rewards politicians for politicizing climate change and turning it into a wedge issue for their own short-term electoral benefit.

Even when the resulting policy swings harm citizens in the long run.

Canada’s recent history is already littered with examples of destructive policy lurch on climate.

In 2002, a Liberal government committed Canada to the Kyoto protocol.

In 2012, a Conservative government made us the first signatory in the world to back out.

Provincially, after Doug Ford’s PCs were elected to a “majority” government with a mere 40% of the vote in 2018, one of the new government’s first actions was to tear up Ontario’s cap and trade system and cancel 758 renewable energy projects.

Australia’s Carbon Tax Policy Lurch: long-term consequences

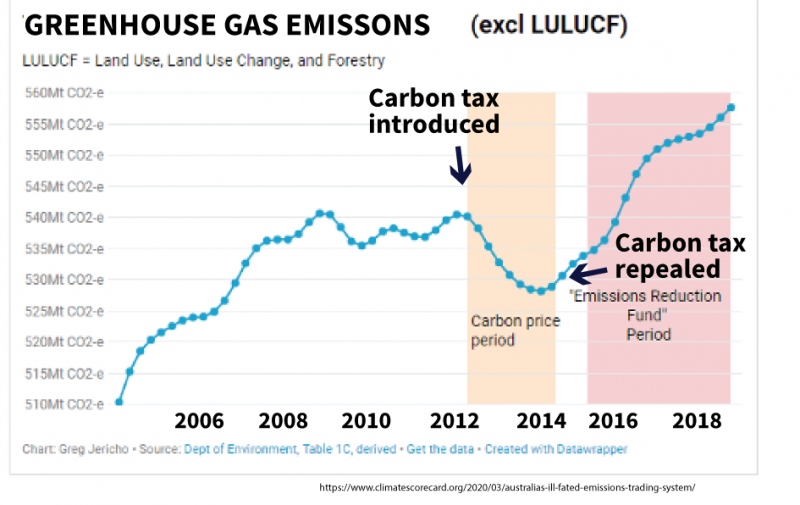

Internationally, the one of the most severe national examples of policy lurch on climate was Australia’s cancellation of their national carbon tax in 2014. Australia is the only OECD country to repeal a national carbon tax—so far.

It’s no coincidence that Australia uses a winner-take-all ranked ballot voting system that replicates (and can even exaggerate) the problems of first-past-the-post, including policy lurch.

Policy lurch was on full display in Australia in 2014 over the issue of a carbon tax. Negotiations for a bipartisan deal to put a price on carbon were scuttled because a faction of MPs (including some hostile to climate action) in the conservative (“Liberal-National”) party were more interested in a wedge issue on which to wage an election battle against the governing Labor Party.

In the end, the carbon tax that had been brought in by the Labor government alone—resulting in the biggest annual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in 24 years—was quickly reversed by the Liberal-National (conservative) government.

The consequences for Australia’s emissions were rapid and drastic, with long-lasting political implications.

Six years after the repeal of the carbon tax, Australia scored a zero on the 2020 Climate Performance Index’s policy scale—dead last.

Even worse, the ability to have a rational political conversation around carbon taxation sustained serious, long-term damage.

As Kane Thorton, CEO of Australia’s Clean Energy Council commented in 2019:

“Even now, in discussion and debate you can still see those scars. Every political leader—across both major parties—has been very substantially impacted by this issue…

“What that means is that what is otherwise a very sensible and accepted approach — putting a price on carbon — is now so difficult that governments either aren’t prepared to go there or it’s done in such a way that there’s such a narrow field of politically palatable options that it’s almost pointless.”

It’s hard to escape the parallels with climate politics in Canada today.

Winner-take-all voting has incentivized the opposition Conservatives to weaponize elements of the climate plan against the unpopular Liberals, turning the most effective climate tools in any government’s toolbox into a polarized debate, fueled by partisanship.

Amidst the growing wave of opposition, provincial Liberal Premiers are pushing the federal Liberal Party to cancel the carbon tax, while Ontario Liberal leader Bonnie Crombie has vowed to never implement a carbon tax in Ontario.

With first-past-the-post, even centrist politicians who pride themselves on “evidence-based policy,” desperate for the votes in swing ridings they need, are foregoing climate leadership in favour of crass political expediency.

Proportional representation: the path to building consensus and protecting climate gains

It’s a fact: Countries with proportional representation act faster, enact stronger policies, and produce better outcomes on climate.

Anyone wondering why might the find part of the answer in a recent article about Norway’s decision to make all vehicles emissions-free by 2025 (emphasis ours):

“Because Norway’s proportional, multi-party system often produces coalition and minority governments, emissions haven’t become politicized, as they have in other countries… The target of making all new cars zero emissions by 2025 was supported by all parties.”

A culture of collaboration between parties, along with some degree of continuity in the parties forming government, can have a profound and lasting impact on climate policy.

In 2020, nine parties in Denmark (including conservatives) cooperated to pass the world’s most ambitious climate legislation. Regardless of which parties form government in future, citizens, investors, and the world can trust that Denmark is committed to tackling climate change over the long haul.

Electoral systems, climate policy, and right-wing populist parties

While shifts in policies and priorities do occur when governments change in countries with proportional representation, the swings are usually much less severe.

In recent years, most of Europe’s governments have shifted to the right. Of the 22 European countries that are rated as free democracies, use proportional representation, and have a parliamentary system, thirteen are now led by right-wing multi-party governments. Another three countries have grand coalitions that include parties on the right of the political spectrum.

Yet instead of experiencing the massive policy reversals on climate that we look doomed to suffer in Canada, many of these same countries continue to top the Climate Change Performance Index year after year, even as governments change hands.

Simply put, policies built with multi-party support are built to last.

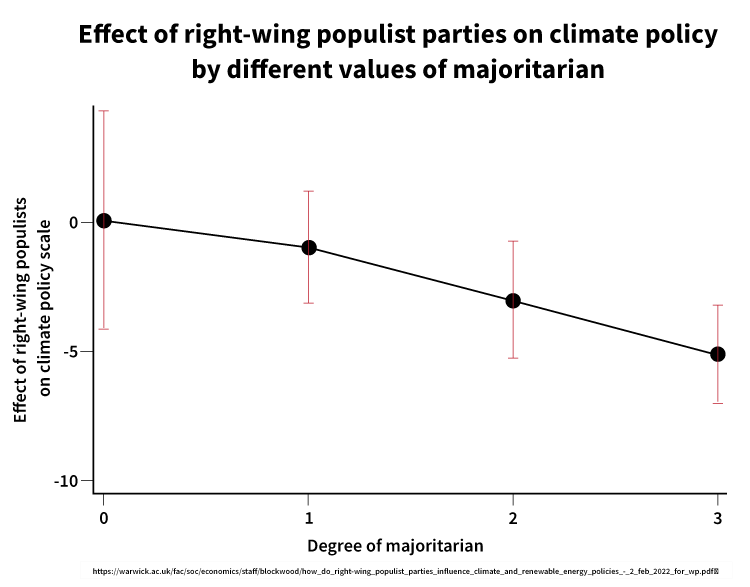

Even when right wing populist parties―who are usually hostile to climate action―are elected, long-term climate plans and targets can endure. Recent research assessing the impact of right-wing populist parties in thirty-one OECD countries shows proportional representation mitigates their impact on climate policy.

It’s in countries with winner-take-all electoral systems, the researchers concluded, that “climate policy can be the most vulnerable to the influence of right wing ‘mainstream’ populists coming to power” and “their negative effect on climate policy is far more pronounced”.

As Donald Trump declared when he announced at a rally that he would tear up the Clean Power Act in 2017:

“Did you see what I did to that? Boom, gone!”

In 2015, a newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the delegates to COP 2015:

“Canada is back, my good friends. We are here to help. To build an agreement that will do our children and grandchildren proud.

If he were being honest, he would have read aloud the fine print: “As long as I keep my promise on electoral reform.”