The last Yukon election returned a minority government. An all-party committee to examine electoral reform was part of the Confidence and Supply agreement between the Yukon Liberals and the Yukon NDP. The committee has been meeting since July 2021. In the winter and spring of 2022, the committee heard from experts they invited to testify, and conducted a survey which was promoted with a mailout to all Yukon households. In summer 2022, they are doing public hearings in communities across the Yukon. Click here to find out when there is a hearing in your local community!

They committee is to produce a report with recommendations in September 2022.

You can follow Fair Vote Yukon here. If you live in the Yukon and would like to get involved locally, please fill out the Get Involved form and we’ll get back to you ASAP.

On January 26, 2022, Fair Vote Canada presented to the Yukon’s Special Committee on Electoral Reform. Our presentation focused on process: the problems with referendums and the advantages of citizens’ assemblies.

Find below the video of our presentation to the committee, and our written submission. Our presentation to the committee focused on process. The written submission includes information about proportional representation, PR models used in jurisdictions similar to the Yukon and suggestions for PR models to consider for the Yukon. You can find a PDF of the written submission here.

Submission to the Yukon Special Committee on Electoral Reform

Table of Contents

Referendums: a poor choice for quality decision-making

Citizens’ Assemblies: best practice for representative, informed, deliberative decision-making

Appropriate applications

Mandate & facilitation

Another approach to a citizens’ assembly on electoral reform: citizens and politicians together

The case for proportional representation

Defining the problem

Why proportional representation?

Examples of proportional representation in remote areas and/or regions of low population density

Relevant comparisons for the Yukon: Arctic Council Northern Territories

Comparator countries in report by Keith Archer

Electoral systems used in OECD countries

Made-in-Yukon proportional solutions

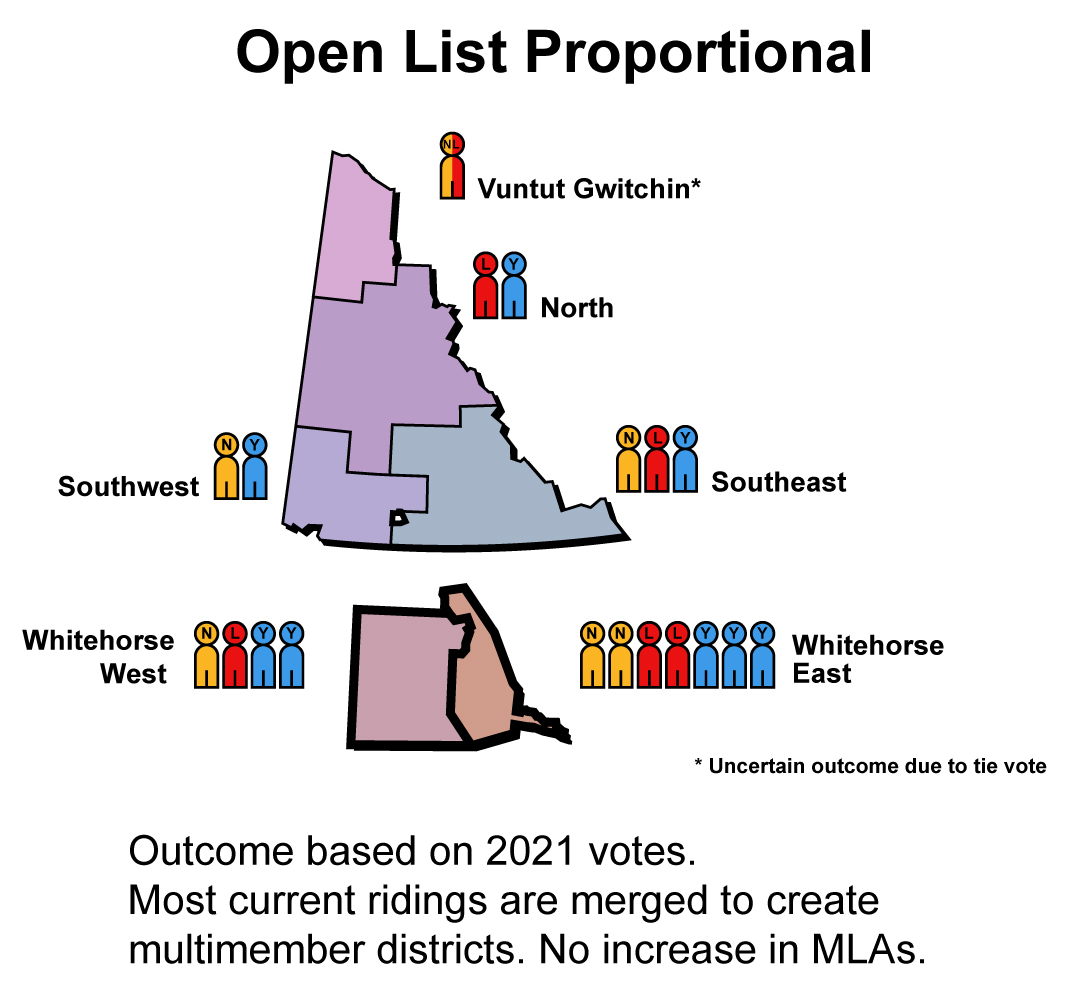

Proposal 1: Open List Proportional in multimember districts (OLPR)

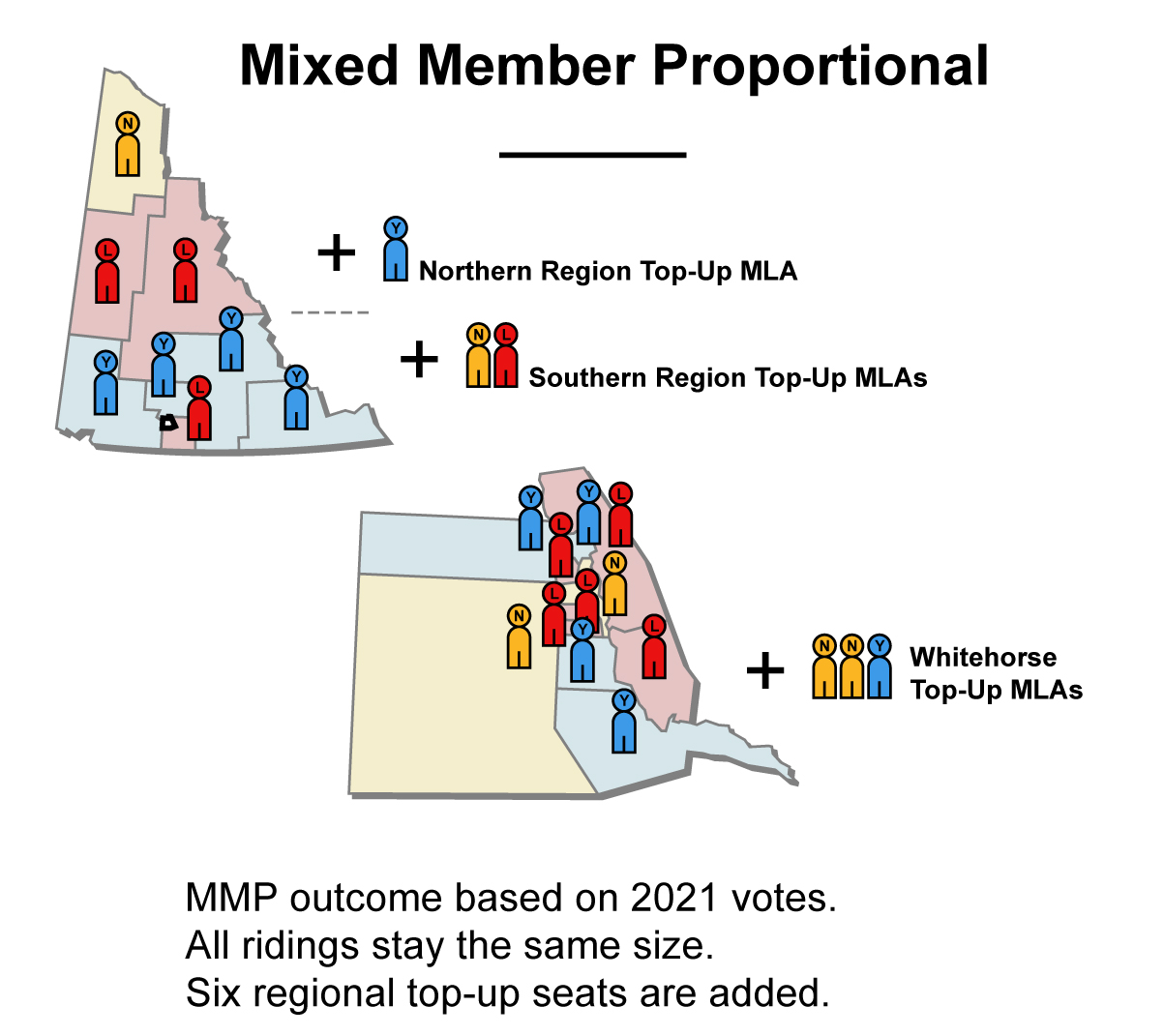

Proposal 2: Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP)

Additional considerations

Yukon-specific benefits of proportional representation

Protection from wipeouts

Substantive representation for minorities and Indigenous People

Special note on Vuntut Gwitchin

Open lists, voter choice and lessening party control

Option to use Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV)

Special considerations on effective number of parties and size of legislature

Legislature size

No expected increase in effective number of parties in the Yukon with PR

Additional suggested experts

General experts on electoral systems and electoral reform

Citizens’ assemblies and referendums

Proportional systems for Yukon

References

Fair Vote Canada (FVC) is a citizens’ campaign for proportional representation. Established as a non-profit in 2001, we have chapters and volunteers across the country, and are funded virtually entirely by donations from individual supporters.

The process matters

What are best practices for informed, deliberative and representative decision-making?

Consulting with citizens before enacting electoral reform is essential.

Given that the electoral system is the mechanism whereby people elect their representatives, gathering input from citizens should be the first step when reform is being considered. The quality, and hence the value, of the input received is determined in great measure by the process used to gather it.

What type of process can produce informed, evidence-based, and truly representative feedback from citizens? What kind of process is centered on a thoughtful consideration of the well-being of all voters and good governance, rather than driven by partisan motivations or misinformation?

Referendums: a poor choice for quality decision-making

Over 80% of OECD countries use proportional representation, and most have adopted PR without recourse to referendums. In fact, only two of 38 OECD countries have brought in proportional representation by referendum: Switzerland in 1918 and New Zealand in 1992.

Canada has a long history of electoral system changes without referendums. This has been the case for the expansion of the franchise to previously excluded populations including women and indigenous peoples, major reforms to election financing and other important features of our electoral system, as well as major changes to the voting system itself in Manitoba, Alberta and BC.

In the ERRE consultations, 67% of the 84 experts who pronounced themselves on referendums recommended against their use on the subject of electoral reform.

There have now been eight electoral referendums in Canada and the UK. These referendums have revealed some key lessons, which are backed up by a considerable body of published research from around the world.

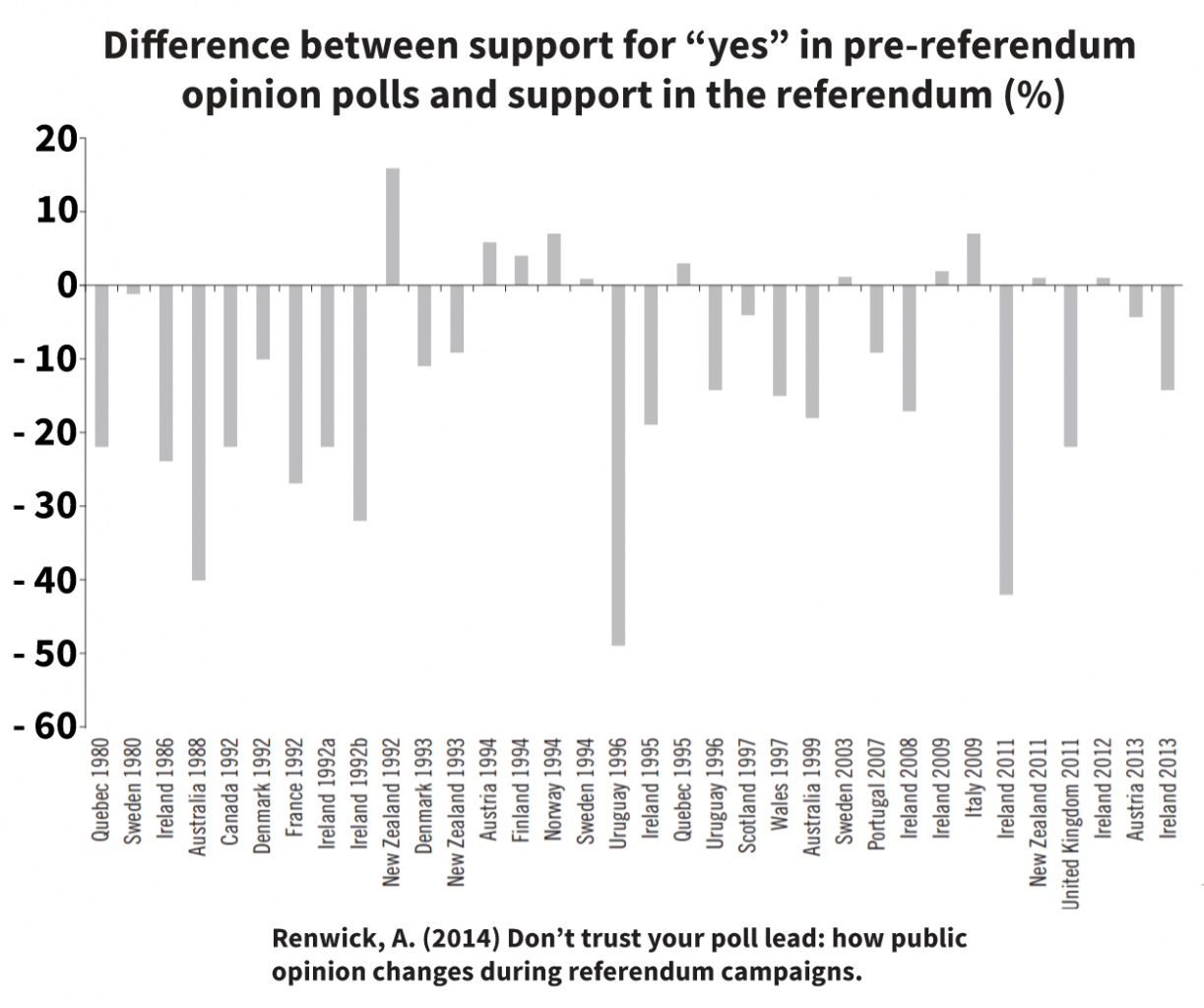

Studies confirm that referendums are not inherently neutral: they are flawed by a consistent and substantial bias towards the status quo.

The side advocating for change, in this case changes to the voting system, must convince voters that life will be better in an imagined future with a new voting system, while the advocates for the status quo can easily capitalize on anxiety, doubt and fear.

Research shows that voter support for change can be expected to drop significantly —often massively—between pre-election polling and voting day.

Grossly misleading or completely inaccurate information disseminated by opponents can have a profound impact on voter decisions, regardless of the availability of official information and fact checkers. In BC, an exit poll showed that huge proportions of “No” voters attributed their decision to vote “No” to various pieces of objectively false information systematically pushed out by opponents. As referendum expert Arthur Lupia states:

“‘No’ campaigns can stay within applicable campaign laws and yet distribute very frightening tales about the consequences of voting ‘Yes’. This is, in fact, the M.O. of ‘No’ campaigns around the world.”

Voters in electoral reform referendums are almost inevitably confused and feel they do not have enough information.

When referendums are held on complex topics, research shows that voters naturally take their cues from opinion leaders. In the case of electoral reform referendums, that usually means party leaders and campaigns motivated by partisanship.

Partisan interests lie at the core of the problem, including:

- the partisan interests of political parties which traditionally benefit from “seat bonuses” under first-past-the-post

- the partisan interests of incumbents who fear losing their seats if the electoral system were to be changed, and

- the partisan preferences of voters themselves.

Referendums exacerbate rather than overcome these challenges, pitting partisan forces against each other with “opponent” and “proponent” groups expected to “duke it out” in a parody of what passes for public education.

In the real world, those calling for referendums on electoral reform are most often those who oppose electoral reform or are ambivalent. This may include political parties and governments whose own caucuses are divided on the issue of electoral reform.

A referendum can be attractive as a neutral-looking political tool for opponents of change, or an escape valve for those who merely wish to be seen as acting on the issue.

Not only will a referendum likely deliver the status quo, but unlike other processes, a referendum can also serve to shut down conversation on electoral reform in a given jurisdiction for decades, since the issue is now perceived as “decided.”

This perception is misleading, however. When asked thoughtful questions even immediately after a referendum, a genuine majority of voters continue to want change and continue to support the core principles of proportional representation.

As Dennis Pilon, one of Canada’s top experts in electoral reform, stated:

Referendum advocates would have us believe that referendums will lead to reasoned debates and decisions on this question, but evidence suggests otherwise. Academic research on the recent provincial use of referendums in voting system reform processes has found chronically low levels of public knowledge and engagement and excessive partisanship in the debate. Choosing a policy consultation approach that evidence suggests will fail is hardly responsible or legitimate. (emphasis added)

For a more detailed look at the factors that drive the vote in electoral reform referendums, please see this presentation given to the Yukon Special Committee on Electoral Reform.

Citizens’ Assemblies: best practice for representative, informed, deliberative decision-making

Citizens’ assemblies are a representative, inclusive, evidence-based way to put citizens’ voices front and centre in complex policy decisions.

Over the past 20 years, the use of citizens’ assemblies and similar processes has grown exponentially around the world. They are used at every level of government to tackle topics ranging from local or provincial/territorial/state level issues to national policy on issues such as climate change.

In October 2021, the PEI legislature voted to conduct a Citizens’ Assembly on Proportional Representation.

Research looking at three full-scale citizens’ assemblies shows that citizens’ assemblies produce consensus recommendations that are relatively free of partisan considerations.

In 2020, the OECD released a report on best practices looking at 289 deliberative citizens’ processes in OECD countries.

Appropriate applications

The experts recommended using deliberative processes for:

- Value-driven dilemmas. Policy issues where there is no clear right and wrong―the goal is to find the common ground.

- Complex problems that require trade offs.

- Long-term issues that go beyond the short-term incentives of electoral cycles. Citizens’ assemblies take political self-interest out of the equation. Participants make decisions based on the public good.

The OECD outlines the benefits to the government and the public of using citizens’ assemblies:

1) Better policy recommendations arise from informed citizen judgments based on quality information and deliberation.

2) Greater legitimacy for hard choices because the recommendations come from the people themselves.

3) Enhanced public trust when citizens see ‘folks just like us’ having an effective role in decision-making.

4) Independence – no “special interests” means a focus on the common good (removing the undue influence of money and power).

5) Diversity of views leads to better policy making.

6) An evidence-based process can help counteract polarization and misinformation.

Mandate & facilitation

To enhance trust and legitimacy, we recommend that a citizens’ assembly on electoral reform for Yukon be given the freedom to examine all options, including keeping the status quo, other winner-take-all systems, and proportional representation.

A successful citizens’ assembly would be fully funded by the government but run by an independent, impartial organization that specializes in deliberative processes. Equitable access would be ensured by covering costs related to travel, lost wages, and childcare.

MassLBP is a private firm which conducts many deliberative processes in Canada, and makes available guides for public agencies wishing to procure such processes or who wish to conduct their own civic lottery. In the case of the Yukon, as part of the random selection process, we strongly recommend that care be taken to include participants from the diversity of Yukon’s First Nations.

Another approach to a citizens’ assembly on electoral reform: citizens and politicians together

Most recommendations for a citizens’ assembly on electoral reform emphasize the importance of the independence of the assembly from political influence. This is understandable, considering that one of the reasons to undertake a citizens’ assembly on this topic—in addition to best practices for meaningful citizen engagement—is to ensure the process is not influenced by politicians who are naturally in conflict of interest when it comes to designing the system that elects them.

A challenge with this approach, however, is that any recommendation for electoral reform that is not subject to an (ill-advised) referendum must go through the legislature. As Ken Carty testified, political leadership is crucial. If politicians don’t buy into what is recommended, no reform will happen.

A novel way to tackle this problem was used in Ireland during their Convention on the Constitution. Established in 2012, the Convention was the precursor to the Irish Citizens’ Assemblies that followed. The Convention followed the deliberative democracy model of citizens’ assemblies. It was tasked with considering a number of possible changes to the Constitution and making recommendations, including on the topic of electoral reform.

Ireland uses Single Transferable Vote. During the Convention, 66 randomly selected, representative Irish citizens, 34 Teachtaí Dála (TDs – the equivalent of MPs), and an independent Chair participated together. They engaged in the work of learning from experts about alternative electoral systems (such as first-past-the-post, MMP, Alternative Vote and List PR), deliberating, consulting in communities, and coming to a consensus recommendation.

In this case, there was an unexpectedly high degree of congruence, with 79% of the participants in favour of keeping the Single Transferable Vote system. They also recommended (86% in favour) that the system be made slightly more proportional, with districts of at least five members (rather than the current 3-5).

The process was, at the time, “uncharted territory” that turned out to be a resounding success. As the Chairman commented in their final report:

“The establishment of the Convention with citizens and politicians was an innovative experiment in deliberative democracy. One interesting outcome was the increased level of mutual respect that developed between citizens and politicians as they worked together.”

The Constitutional Convention paved the way for the Irish Citizens’ Assembly, which in turn set off a domino effect for deliberative democracy around the world.

Although future assemblies in Ireland followed the now well-established model that does not include elected representatives, the experience of the Convention showed how citizens and elected representatives could work together on electoral reform.

The case for proportional representation

Defining the problem

Elections are the heart of a representative democracy. A fundamental test of a healthy democracy is whether what voters say with their ballots is reflected in the legislature. This condition is not satisfied by Yukon’s first-past-the-post system (FPTP).

The winners in each riding are elected by plurality, meaning that the ballots cast for other candidates are not reflected in the composition of the legislature. On April 12 2021, over 9924 voters (52.2%) cast ballots which elected no one—they were unable to make their votes count.

This ratio is typical of first-past-the-post elections across Canada, the US and UK (the only major Western democracies still using this system). The vast majority of modern democracies use more inclusive, proportional voting systems.

Under first-past-the-post, false majorities based on 39-40% of the vote, as Yukon had in 2011 and 2016, are endemic. Since 1978, every election except 2021 has produced a “majority” government elected with less than 50% of the vote.

Yukon’s democratic deficit manifests itself in many other ways as well:

- Voters may feel compelled to vote strategically to block the election of a less desired candidate.

- Shifts from one majority government to another can lead to expensive “policy lurch,” as new governments undo policies enacted by the previous one.

- Majoritarian voting systems create short-term thinking and force parties to focus their policy decisions on four-year electoral cycles. Constant campaigning aimed at winning the next 39% majority sidelines long-term solutions in favour of inaction or quick fixes.

Why proportional representation?

Proportional representation ensures that the composition of the legislature as well as the policies enacted reasonably reflect the values and choices of a voting majority by providing representation in proportion to votes cast.

PR provides positive voter choice and changes the dynamic of government by replacing the combative discourse of winner-take-all systems like first-past-the-post and Alternative Vote (ranked ballot in single-member ridings) with inter-party collaboration and consensus building.

Over 90 countries globally and over 80% of OECD countries use some form of proportional representation. Included in that number are a few jurisdictions which face challenges of geography or small population comparable to Yukon, which we will examine more closely, below.

Comparative research shows that PR countries enjoy stable governments and successful democracies. They tend to outperform winner-take-all countries in terms of environmental outcomes, equality, health and fiscal responsibility; in addition, voters have a more favourable perception of their democratic institutions.

Results from past consultations

Since 1977, 18 separate processes in Canada have studied the same question that Yukon’s Special Committee on Electoral Reform is examining now, including identifying the core values important to voters. All of them concluded that we need to make our electoral system more proportional.

Examples of proportional representation in remote areas and/or regions of low population density

The Yukon’s challenges in designing an electoral system are significant, but not unique. Jurisdictions which have wrestled with similar issues have arrived at different, tailor-made solutions which can inform the discussion in Yukon.

In addition to the values listed above, we believe that questions of geography and density are critically salient to system design.

Our analysis of Arctic Council countries and territories, below, complements the jurisdictions highlighted in Dr. Archer’s report, which confines itself to jurisdictions with similar sized legislatures. Including jurisdictions with similar populations or geography shifts the focus to places which are perhaps more easily comparable to Yukon.

In addition, many of the countries and territories referenced by Dr. Archer have serious democratic deficits. For example, in the last two elections in Barbados, the Labour party swept all the seats, leaving opposition parties completely unrepresented in parliament despite having won significant vote share―a situation which is clearly less than desirable. In Grenada in 2018, the same situation occurred with the New National Party winning 100% of the seats with 59% of the vote in parliament.

Dr. Archer’s report also excludes sub-national territories which have representation in their national legislatures. This criteria would exclude the Yukon itself and many other similar territories.

Other Arctic Council members, particularly those recognized to have strong democratic institutions, illustrate alternative approaches to governing outlying and autonomous regions and territories which warrant consideration by this committee. Not all jurisdictions are perfect analogues to the Yukon’s situation, but then again every region is different in some way.

Relevant comparisons for the Yukon: Arctic Council Northern Territories

Greenland

Population 56,367

Area 2.166 million km²

Distance from Capital 3,532 km

No road access between communities or capital

90% Indigenous

Legislature: Inatsisartut

31 members

Open-list proportional representation

Faroe Islands

Population 53,358

Area 1,339 km²

Distance from Capital 1,308 km

No road access to some communities and none to the capital.

Legislature: Løgting

33 members

Open-list proportional representation

Norwegian Finnmark

Population 75,540

Area 48,618 km²

Distance from Capital 1397 km

Road access to most communities and to the capital

Legislature: Finnmark Fylkestinget (recently reinstated)

35 members

Open list proportional representation

Swedish Norrbotten County

Population 251,080

Area 98,244.8 km²

Distance from Capital 726 km

Road access to all communities and to the capital

Legislature: County Administrative Board of Norrbotten County

71 members

Open list proportional representation

Finnish Lapland

Population 177,161

Area 100,366 km²

Distance from Capital 698 km

Road access to all communities and to the capital

Legislature: Lapland Regional Council,

59 members

Open-list proportional representation

Additionally, Norway, Finland and Sweden each have their own Sámi Parliament for the self-governance of the Indigenous Sámi peoples.

Sámi Parliament of Norway

39 members

Open-list proportional representation

Sámi Parliament of Sweden

31 members

Open-list proportional representation

Sámi Parliament of Finland

21 members

Open-list proportional representation

For comparison, the countries/territories included in Dr. Archer’s analysis are listed below. Fully half of these countries/territories are smaller in area than the City of Whitehorse, and one is just one third the population of the riding of Vuntut Gwitchin.

Comparator countries in report by Keith Archer

| Country/Territory | Elected Members | Electoral System | Population | Area (km2) |

| ANDORRA | 28 | Parallel | 77,265 | 468 |

| ANGUILLA | 7 | FPTP | 15,094 | 102 |

| ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA | 17 | FPTP | 96,286 | 440 |

| ARUBA | 21 | List PR | 106,766 | 180 |

| BARBADOS | 30 | FPTP | 287,371 | 439 |

| BELIZE | 29 | FPTP | 397,621 | 22,965 |

| BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS | 13 | FPTP | 30,237 | 153 |

| CAYMAN ISLANDS | 15 | Bloc Voting | 65,720 | 264 |

| COMOROS | 18 | TRS | 869,595 | 1,862 |

| COOK ISLANDS | 24 | FPTP | 17,459 | 236.7 |

| DOMINICA | 21 | FPTP | 71,991 | 751 |

| FALKLAND ISLANDS | 8 | Bloc Voting | 12,000 | 2,840 |

| GIBRALTAR | 15 | Limited Voting | 33,691 | 6.8 |

| LIECHTENSTEIN | 25 | List PR | 38,137 | 160.5 |

| MONACO | 24 | Parallel | 39,244 | 2.2 |

| MONTSERRAT | 9 | TRS | 4,992 | 102 |

| MICRONESIA | 14 | FPTP | 115,021 | 702 |

| NAURU | 18 | Majoritarian Borda Count | 10,834 | 21 |

| NETHERLANDS ANTILLES | 22 | List PR | 26,223 | 999 |

| NIUE | 20 | FPTP & Bloc | 1,620 | 261.5 |

| PALAU | 22 | FPTP | 18,092 | 458.4 |

| PITCAIRN ISLANDS | 4 | SNTV | 67 | 47 |

| SAINT HELENA | 12 | FPTP & Bloc | 5,633 | 394 |

| SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS | 10 | FPTP | 53,192 | 269.4 |

| SAINT LUCIA | 17 | FPTP | 183,629 | 617 |

| SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES | 15 | FPTP | 110,947 | 389 |

| TONGA | 9 | Bloc Voting | 105,697 | 748.5 |

| TURKS & CAICOS ISLANDS | 13 | FPTP | 38,718 | 948 |

| TUVALU | 15 | FPTP | 11,792 | 25.9 |

| YUKON | 19 | FPTP | 43095 | 482,443 |

We also offer a summary of what Canada’s OECD peers use for electoral systems at the national level, below.

Electoral systems used in OECD countries

| Country | System |

| Australia | Majoritarian |

| Austria | PR |

| Belgium | PR |

| Canada | Majoritarian |

| Chile | PR |

| Czech Republic | PR |

| Denmark | PR |

| Estonia | PR |

| Finland | PR |

| France | Majoritarian |

| Germany | PR |

| Greece | Mixed |

| Hungary | Mixed |

| Iceland | PR |

| Ireland | PR |

| Israel | PR |

| Italy | Mixed |

| Japan | Mixed |

| Korea | Mixed |

| Latvia | PR |

| Luxembourg | PR |

| Mexico | Mixed |

| Netherlands | PR |

| New Zealand | PR |

| Norway | PR |

| Poland | PR |

| Portugal | PR |

| Slovak Republic | PR |

| Slovenia | PR |

| Spain | PR |

| Sweden | PR |

| Switzerland | PR |

| Turkey | Mixed |

| United Kingdom | Majoritarian |

| United States | Majoritarian |

Made-in-Yukon proportional solutions

The Yukon’s challenge is to create a PR system based on the territory’s geography, historical traditions, and values of special importance. Fortunately, there are many examples around the world to draw on.

All models of proportional representation that we support feature:

- Proportional results (30% of the vote = about 30% of the seats)

- Local representation

- Regional representation

- More voter choice

- Direct election of representatives and accountability to voters (no closed party lists).

With proportional representation:

- Almost every vote will count to define the makeup of the legislature

- Almost every voter will help elect a representative who shares their values

- All regions will usually have representation in both government and as part of the opposition

- A single party will no longer be able to attain a majority government with just 40% of the vote

- Cooperation and compromise will become the norm.

In 2016, Fair Vote Canada recommended that the federal electoral reform committee consider three possible types of PR systems. We continue to endorse these three options, any of which could be tailored for the Yukon:

Since geography and low population density is a challenge in Yukon, we would like to present some information on how PR works in comparable situations and offer some suggestions of specific PR models which may be a good fit.

Proposal 1: Open List Proportional in multimember districts (OLPR)

International Use: Nordic Countries (including Greenland and Faroe Islands)

Description:

- Parties nominate multiple candidates in a riding.

- Voters make a mark next to the candidate of their choice.

- If a party’s candidates get a given X% of the vote, that party gets X% of the seats.

- The candidates with the most votes for that party take the awarded seats.

- Any independents that get the requisite share of the vote are also elected.

Note that this is based on merging existing ridings, and keeps the legislature at 19 members. New boundaries could be drawn by a boundary commission, and MLAs could be added either to improve proportionality or reduce riding sizes.

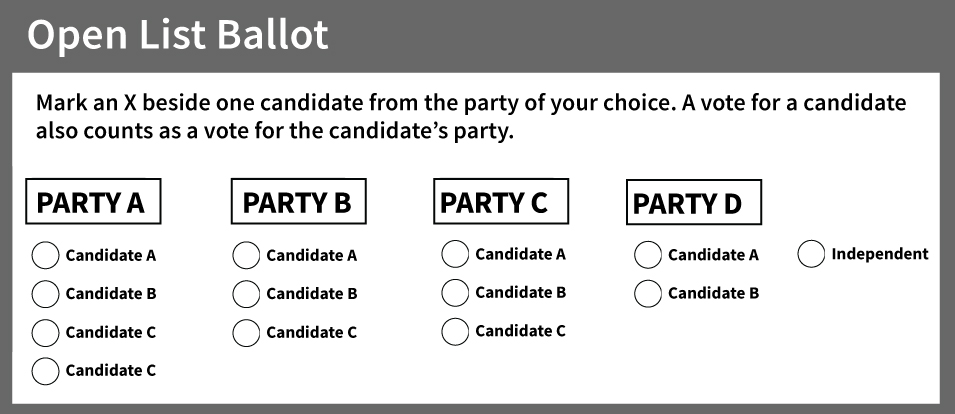

Open List PR: Sample ballot

Proposal 2: Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP)

International Use: Germany, New Zealand, Scotland, Wales

Description:

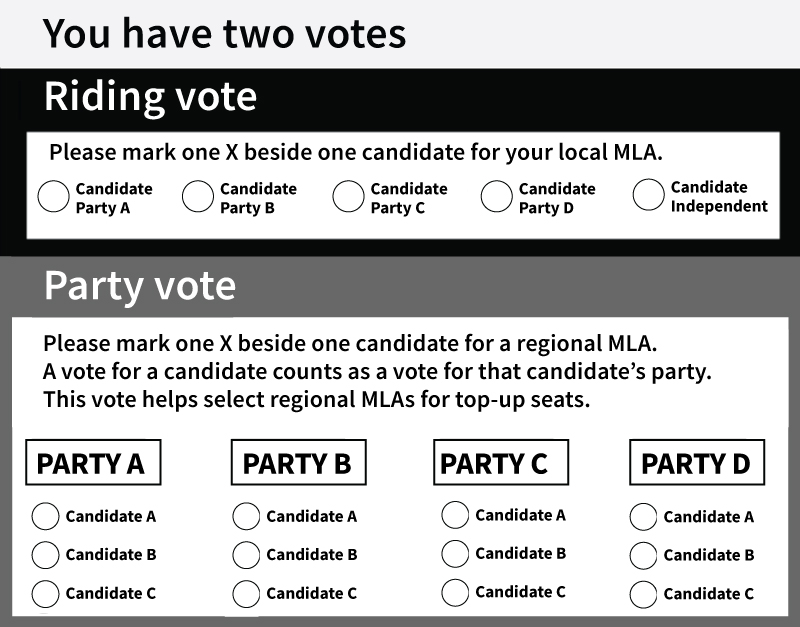

- Parties nominate a single candidate for each local riding and multiple candidates for each region.

- Voters make a mark next to the local candidate of their choice, and make another mark next to the regional candidate of their choice.

- Counting proceeds unchanged from the status quo in local ridings.

- In a region, if a party’s candidates get a given X% of the vote, that party gets X% of the seats.

- The candidates with the most votes for that party win the regional seats.

- Any regional or local independents that get the requisite share of the vote are also elected.

Note that this is based on grouping existing ridings into regions, and grows the legislature to 25 members. New boundaries could be drawn by a boundary commission, and MLAs could be added or subtracted as desired.

MMP: Sample ballot

Additional considerations

Yukon-specific benefits of proportional representation

Protection from wipeouts

One advantage of greater proportionality that Yukon parties should be aware of relates to wipe-out and near-wipeout situations. Due to the tension between Yukoners’ diverse voting preferences and the current electoral system that does not support that diversity, each party has experienced wipe-outs or near-wipeouts, where despite getting a large (~25%+) share of the vote they are reduced to a rump caucus of 1-2 seats. Examples of this include:

- NDP 2016 (26% vs 2 seats)

- Liberals 2011 (25% vs 2 seats)

- Liberals 2002 (29% vs 1 seat)

- Yukon Party 2000 (24% vs 1 seat)

- Liberals & NDP 1978 (28% vs 2 seats & 20% vs 1 seat)

Proportional representation would protect parties and their voters from these undeserved near-wipeouts, preserving institutional memory/capacity and giving opposition parties a stronger voice, regardless of who is in government.

This does not mean that there would be MLAs that could not be removed by voters, but rather that removal would be caused by a rejection from voters rather than a quirk of boundaries and the voting system.

Substantive representation for minorities and Indigenous People

Dr. Archer rightfully focuses a great deal on defining descriptive representation (described in his report as the degree to which the populace’s demographic diversity is reflected in the legislature), but neglects the issue of substantive representation, which is the degree to which each segment of the populace is represented by elected officials.This is more difficult to measure, but studies have shown that proportional voting systems promote greater substantive representation for minority groups than first-past-the-post, even when controlling for equal descriptive representation.

Put simply, Indigenous issues would be given greater weight under proportional representation.

Special note on Vuntut Gwitchin

We recognize the special circumstances surrounding this district and community, and do not propose any alterations to this district. However, we do note that under our mixed member proposal, residents of Vuntut Gwitchin would also have their votes included in the selection of the northernmost region’s regional representative.

Open lists, voter choice and lessening party control

Many voters and politicians alike express concerns about excessive central party control both under the current first past the post electoral system and under potential alternative systems. We feel these concerns are valid, and as an organization we have a stated preference for reforms that strengthen the link between MLAs and voters, and weaken the amount of control central party organizations can exert over voters’ options and politicians’ careers.

Scholars such as Shugart, Carey, Farrell and McAllister have categorized electoral systems not only by proportionality, but also by how candidate or party-centred an electoral system is. Without going into excessive detail, candidate-centred systems are generally those that reward candidates for having a high profile, allowing them to dissent when needed, whereas party-centred systems put greater weight on conformity.

Open-list systems are generally rated as among the most candidate-centred voting systems, along with single transferable vote, and more so than the existing first past the post system.

Open lists afford voters greater choice while improving their ability to hold MLAs to account. They have also been shown to facilitate the growth of “bigger tents” within parties than closed lists, with a wider diversity of views represented in every party.

Voting with an open list is simple and familiar to voters, since both open lists and first-past-the-post involve making a mark next to the candidate of your choice.

Open lists also serve to reduce central party control both compared to closed lists and first past the post, allowing dissident MPs to directly make their case to voters rather than be deprioritized on a closed list. This again promotes more within-party diversity, as well as voter choice, and has been found to improve voter satisfaction.

The lower barriers to entry of a proportional system can also give dissident MLAs a better chance of success when running for re-election as an independent, serving as an additional “relief valve” for within-party dissent.

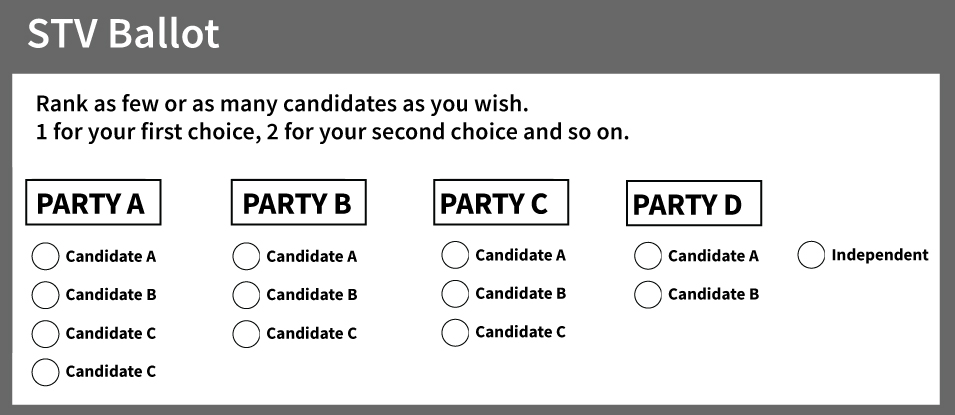

Option to use Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV)

Instead of using an Open List ballot, candidates in the multimember districts described in the Open List PR model can be elected using Single Transferable Vote, providing voters with even greater flexibility.

Instead of marking one “X” with an open list (which counts for one individual candidate and also as a vote for a party), with STV voters can rank as few or as many individuals as they want, in any order they want across the ballot.

The most popular candidates in any given district will be elected.

STV delivers proportional results while giving voters a greater ability to express their preferences for candidates and see those preferences reflected in their legislature.

STV was recommended by the British Columbia Citizens Assembly (2004), who identified their most important values as proportional representation, local representation and voter choice. It is used nationally in Ireland, in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Tasmania. It is also used in Scotland for all local elections and New Zealand for some local elections.

In Canada, STV was used to elect provincial MLAs in Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton for 30 years.

While some experts may dismiss STV out of hand as too complicated (“the option for voting system nerds”), as the original proportional system, it is quite simple for voters to use. As the New Zealand government’s website describes it, STV means “Simple to Vote”. The rate of spoiled ballots in Ireland was lower in their last election than in Canada’s.

Counting the STV ballots does require more steps than other electoral systems. Although voters will easily understand that the results are roughly proportional, how the votes for individual candidates translate into seats is more complex than other PR systems.

Simple animations such as this one from Ireland or from the Tasmanian Electoral Commission are helpful. Ireland’s electoral commission provides voters with animations (press the Play button above the graph) showing how the counting progressed in their districts.

STV: Sample Ballot

Special considerations on effective number of parties and size of legislature

Legislature size

Dr. Rein Taagepera noted that legislatures in the world typically follow a simple rule in terms of the size of their membership, which is that legislatures typically have members equal to the cube root of the jurisdiction’s population. For example, in Canada this would correspond to having 336 MPs, compared to the 338 actually in the House of Commons. The major outliers to this law are generally former British colonies and their subnational legislatures, with fewer representatives than the international average. In Canada and in US states, 55% of the Cube Root Law is typical for state and provincial legislatures.

Applied to the Yukon, the Cube Root Law would suggest 35 MLAs. 55% of the cube root would be 19 MLAs. Therefore, 19 MLAs could be said to reflect Canadian norms, and 35 MLAs international norms. We recommend that the legislature size fall within those two bounds and have kept our models within this range.

No expected increase in effective number of parties in the Yukon with PR

Dr. Rein Taagepera , Dr. Huey Li and Dr. Matthew Shugart developed a Seats Product Model to predict the effect of the design of electoral institutions on the party system that develops from them. We will not review their work in depth as it is rather complicated, but should this interest the committee we encourage you to reach out to them to provide their input directly.

They use a term called the effective number of parties to characterize the level of diversity in a legislature and among voter preferences. Currently, the effective number of parties by votes cast in the Yukon is 2.95, and by seats is 2.64. However, based on the Seats Product Model one would expect values of 1.92 and 1.64. Put simply, Yukoners are voting for and electing a much more diverse legislature than would be expected based on the legislature’s structure.

In practical terms, this means that neither a modest increase in the size of the legislature nor the adoption of a proportional method of elections would be expected to substantially increase the number of parties elected. While there are no guarantees in politics, and indeed the party system will continue to evolve regardless, it is worth noting that the increase in the number of parties in New Zealand after the implementation of electoral reform in 1996 was temporary: voting patterns had reverted to pre-reform norms by 2005. In fact there has been greater stability in the party system in the last 15 years than in the 15 years leading up to reform.

If the desire is to increase the number of parties represented in Yukon’s legislature, we expect that the number of seats would need to increase to at least 40, regardless of whether or not a proportional system is implemented.

Additional suggested experts

The Yukon Special Committee on Electoral Reform may wish to call additional subject matter experts to testify. We highlight the following for your consideration.

General experts on electoral systems and electoral reform

Matthew Shuggart, Professor Emeritus, University of California, San Diego. Professor Shugart’s research focuses on how the details of political institutions affect the quality of democratic governance. Expert on electoral system design. Full biography.

John Carey, Professor of Government, Dartmouth College. Expert on electoral system design. Full biography.

Citizens’ assemblies and referendums

David Farrell, Professor of Politics at University College Dublin. Expert on electoral systems and deliberative democracy, particularly the Irish Conventionon the Constitution and Irish Citizens’ Assemblies. CV here.

Lawrence LeDuc, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto. Expert on referendums, deliberative democracy, electoral reform and citizens’ assemblies. Full CV here.

Jonathan Rose, Professor of Political Science, Queen’s University. Academic Director for the Ontario Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform and co-author of When Citizens Decide: Lessons from Citizens’ Assemblies on Electoral Reform (Oxford, 2011). Full biography.

Proportional systems for Yukon

Ryan Campbell, electoral system design expert, board member Fair Vote Canada

Byron Weber Becker, electoral system design expert. Engaged by the federal ERRE committee to do simulations for them. Full biography.

References

Carty, K., Cutler, F. and Fournier. P. (2009). Who Killed BC-STV? UBC Study Explains.

Citizens’ Reference Panel on Pharmacare in Canada (2016). Necessary Medicines : Recommendations of the Citizens’ Reference Panel on Pharmacare in Canada : Final Report.

Canadian Citizens’ Assembly on Democratic Expression. (2022) “Canadian Citizens’ Assembly on Democratic Expression: Recommendations to strengthen Canada’s response to the spread of disinformation online.” Ottawa, Public Policy Forum.

Fair Vote Canada (2021). A look at the evidence for proportional representation: summary of research.

Goss, Zander and Renwick, Alan (2016) Fact-checking and the EU referendum. The Constitution Unit Blog.

Fact-checking and the EU referendum.

Hoff, George. Covering Democracy: The coverage of FPTP vs. MMP in the Ontario Referendum on Electoral Reform, Canadian Journal of Media Studies, Vol. 5(1) 2009.

http://cjms.fims.uwo.ca/issues/05-01/hoff.pdf

Leduc, Lawrence (2022). Affidavit of Lawrence Leduc in the Charter Challenge by Springtide and Fair Voting BC. NOTE: Full resume of Lawrence Leduc including numerous articles on referendums, deliberative democracy and electoral reform can be found on pages 29-62.

Leduc, Lawrence (2007). Voting NO: The Negative Bias in Referendum Campaigns. Prepared for presentation at the ECPR Joint Sessions Workshops Helsinki, 7-12 May 2007.

Leduc, Lawrence (2009). The Failure of Electoral Reform Proposals in Canada. Political Science 2009 61: 21. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00323187090610020301

Leduc, Lawrence and Baquero, Catherine. (2008). The Quiet Referendum: Why Electoral Reform Failed in Ontario. Prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, University of British Columbia, June 4-6, 2008

Leduc, Lawrence (2002). Opinion change and voting behaviour in referendums. European Journal of Political Research 41: 711–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00027

Leduc, Lawrence (2009). Campaign tactics and outcomes in Referendums: A comparative analysis. Chapter in Maija Setälä and Theo Schiller (eds.), Referendums and Representative Democracy:Responsiveness, Accountability and Deliberation (London, Routledge, 2009)

LeDuc, Lawrence. “Referendums and Elections: How Do Campaigns Differ?”, in David M. Farrell and Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Do Political Campaigns Matter? Campaign Effects in Elections and Referendums (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 145–62.

Lupia, Arthur and Johnston, Richard (2001). Are Voters to Blame? Voter Competence and Elite Maneuvers in Referendums. In Mendelsohn, M. Parkin, A., Editors. (2001). Referendum Democracy: Citizens, Elites and Deliberation in Referendum Campaigns (pp. 191-210). New York: Palgrave.

Lupia, Arthur (2016). What Citizens Know about Referenda: Facts and Implications (submission to the federal electoral reform committee). (Arthur Lupia’s work can be found here).

MassLBP (2019). How to commission a Citizens’ Assembly or Reference Panel: Advice for public agencies procuring long-form deliberative processes.

MassLBP (2017). How to run a civic lottery: Designing fair selection mechanisms for deliberative public processes.

MassLBP (2020). The Deliberative Wave: Securing a future for democratic politics.

MIT Media Lab (2018). Project: The spread of true and false information online.

OECD (2020) Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave.

OECD (2021). Good Practice Principles for Deliberative Processes for Public Decision Making.

PEI Legislative Assembly (2020). Motion 71: Establishing a Citizens’ Assembly for Proportional Representation.

Pilon, Dennis (2016). A referendum on the voting system would be undemocratic and immoral. Hill Times

Pilon, Dennis. “Investigating Media as a Deliberative Space: Newspaper Opinions about Voting Systems in the 2007 Ontario Provincial Referendum,” Canadian Political Science Review, 3: 3 (September 2009): 1-23.

Pilon, Dennis. “The 2005 and 2009 Referenda on Voting System Change in British Columbia,” Canadian Political Science Review, 4: 2-3 (June-September 2010), 73-89.

Pilon, Dennis. The Politics of Voting: Reforming Canada’s Electoral System, (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2007), 209pp.

Pilon, Dennis. Wrestling with Democracy: Voting Systems as Politics in the Twentieth Century West, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 394pp.

Renwick, A. (2014) Don’t trust your poll lead: how public opinion changes during referendum campaigns. In: Cowley, P. and Ford, R. (eds.) Sex, lies and the ballot box: 50 things you need to know about British elections. Biteback, London, pp. 79-84.

Renwick, Alan. (2014). Scotland’s Independence Referendum: Do We Already Know the Result? Open Democracy.

Research Co (2018). BC Referendum Exit Poll.

Russell, Leonard. Special Committee on Electoral Reform, October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017 from https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/ERRE/meeting-38/evidence

Sass, T.R. and Mehay, S.L. (2003), Minority representation, election method, and policy influence. Economics & Politics, 15: 323-339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0343.00127

Soderland, Peter. Candidate-centred electoral systems and change in incumbent vote share: A cross-national and longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 55:321-339.

Stevens, Daniel and Banducci, Susan (2013). One voter and two choices: The impact of electoral context on the 2011 UK referendum. Electoral Studies, 32, 274-284.

Tanguay, Brian and Stephenson, Laura. Ontario’s Referendum on Proportional Representation: Why Citizens Said No. Institute for Research on Public Policy Choices, Vol. 15, no. 10. http://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/research/strengthening-canadian-democracy/why-do-canadians-say-no-to-electoral-reform/vol15no10.pdf

Trueblood, Leah. Yes and No. The Problems with Bad Referendums. On CBC’s Ideas. Retrieved July 7, 2017 from http://www.cbc.ca/listen/shows/ideas/episode/12680953

Vowles, Jack (2012). Campaign claims, partisan cues, and media effects in the 2011, British Electoral System Referendum. Electoral Studies, 32, 253-264.

Wiseman, Nelson (2016). Testimony to the federal ERRE committee.