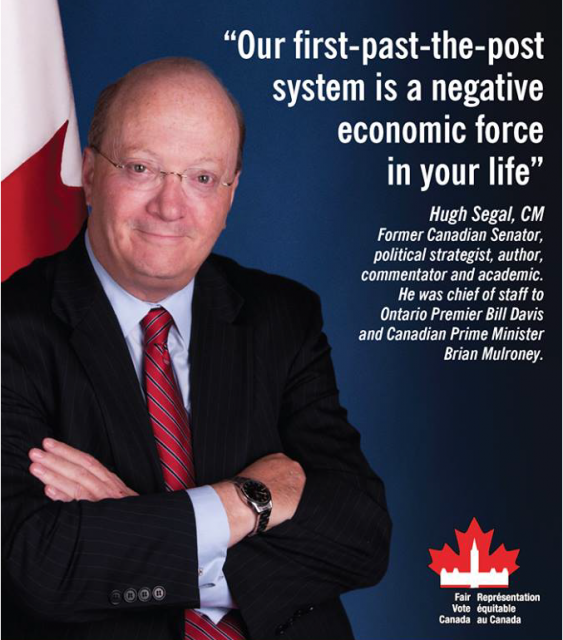

Hugh Segal on the economics of electoral reform

There is a great tendency in modern digital societies for debate and controversy to embrace the apparently urgent as opposed to the truly important. This tendency is made worse by key stakeholders who have huge self-interests protected by the status quo. There are few challenges facing Canadians where this is truer than that of electoral reform.

Whether one is on the right or left in our politics, whether one is part of the politically disinterested, either by virtue of being very wealthy or very poor, whether one is young or old, a small business person, union member, student or recently laid off – our first past the post system is a negative economic force in your life.

Here’s how and why:

Parliaments and legislatures elected through the first past the post system, where only the winning votes are counted in any election, often represent far less than fifty percent of those who voted in any constituency-in some cases this number could be as low as thirty-five percent – in the vast majority of cases those who govern, oppose, question or engage as elected MPS or MPPS, speak for very few of their voters-almost always a minority, regardless of party.

As first-past-the-post elections manufacture contrived majorities where thirty-eight percent of electors can elect sixty percent of the seats, majority governments who classically eschew compromise with other parties get to impose economic policies from the right or left that do not reflect a balanced or inclusive economic policy framework. This can and has led to bad policy, excessive or inadequate tax initiatives, tilted labour relations, excessive or incompetent regulatory régimes. All of these can and have cost Canada and provinces economic slowdowns, wild lurches from one economic policy to another and so on. This costs us vital time and setbacks on issues like jobs, investment, tax reform, poverty reduction, and education. These are setbacks that hurt people’s lives, aspirations and economic and social prospects.

A dysfunctional electoral system that discourages participation, helps reduce voter turnout, favours established parties, manufactures illegitimate and undemocratic majorities, is not a detail or sidebar. It is central to how effectively a society’s economic and social framework operates. Those frameworks are established through elected parliaments from which governments derive the basis for governing. If the basis of those elections is systematically exclusionary, economic and social policy are unavoidably flawed, short term and shallow.

As those who are elected under the first-past-the-post regime, have won within that regime’s strictures, they are unlikely to want it to change. This strident complacency leads to an unwelcome tolerance for unrepresentative democracy.

Is economic policy contained in a budget, approved by a legislature that was chosen by the 55 percent of eligible voters of turned out to vote legitimate? What if the government that proposed the budget had a majority, but was only elected by 40 percent of the 55 percent?

Economic policy that is set by a government barely representing in this way as few as 20 percent of eligible voters is unlikely to be strong or deeply rooted in economic or social reality as experienced by that vast majority of Canadians. This is true in almost every province and Ottawa, except when leaders like Mulroney, Diefenbaker or Lougheed received huge majorities in high turn out elections.

Our present system of manufactured false majorities makes for fiscal and economic policy that may be both narrow and disconnected. This is bad for business, labour, and the entire economy.

Electoral reform would break this cycle and create incentives for a much broader economic debate where truly democratically representative legislatures and parliaments would make budget, trade, fiscal and tax policy more truly reflective of how people actually voted.

Economic policy only works when it reflects economic and social reality. In a democracy that reality is made real by parliaments that are representative of how people actually voted. First past the post alters,dilutes, frustrates and often negates how people actually voted. Economic policy based even in part on this distortion cannot but be distorted itself.

Proportional representation is the only way to set this right.

Hugh Segal is currently serving as the fifth Master of Massey College at the University of Toronto. Full biography here:

https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/profile/segal-hugh/

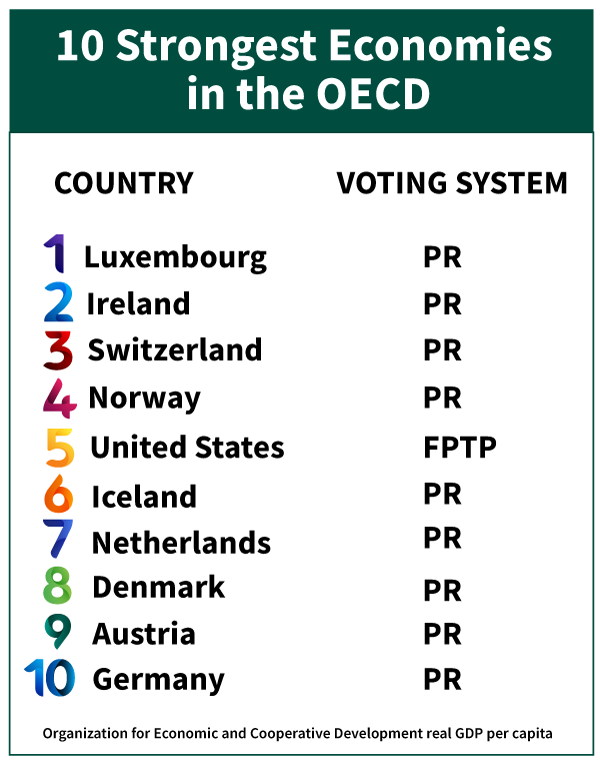

Knutsen (2011) looked at 3,710 country-years of data covering 107 countries from 1820 to 2002. He found that proportional and semi-proportional systems produced an “astonishingly robust” and “quite substantial” increase in economic growth compared to winner-take-all systems. As he explains, “different studies suggest that going from First-past-the-post to a PR system gives between one half and one extra percentage point of growth” (personal communication, May, 2019).

Norris (2011, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard), examining the relationship between different aspects of democratic institutions and economic growth concluded, “the direct effects of proportional representation electoral systems are also significantly related to income, further confirming Knutsen’s conclusions.”

Alfano and Baraldi (2015) studied 91 countries from 1979–2010 and found the relationship between proportional and economic growth appeared as a curve with the growth rate reaching its maximum value in correspondence with an intermediate degree of proportionality, corresponding to a Gallagher index about equal to 6.5. A score of 6.5 – associated with the highest level of economic growth – is a similar level of proportionality to Scotland and Ireland, which use Mixed Member Proportional and Single Transferable Vote with local regions/districts – proportionality combined with local representation).

They explain this result by suggesting that:

…in systems with an intermediate degree of proportionality, the beneficial accountability characteristics of plurality/majoritarian systems (which may induce office-motivated politicians to enact growth-promoting policies) are put beside the beneficial representativeness characteristics of PR (which induce politicians to enact public policies that benefit broad rather than narrow interests). Secondly, a mixed method enhances both political and government stability stimulating a relatively high growth rate.

**The Gallagher Index measures how proportional election results are. A Gallagher Index of 0 would be perfectly proportional – the higher the score, the more disproportional the results, with Canada falling at score of around 12 – highly disproportional. Click here for information on the Gallagher Index, measuring disproportionality in elections).

For more information about proportional representation and economic growth, economic stability, debts/deficits and government spending, see https://www.fairvote.ca/factcheckeconomy/