For the purposes of this article, we define a political extremist as someone whose political views are well outside the mainstream and are strongly opposed or seen as unreasonable by most people.

Which type of voting system gives “extremist” politicians more power?

Politicians with extreme political views and voters who support those views exist in every country, regardless of the electoral system.

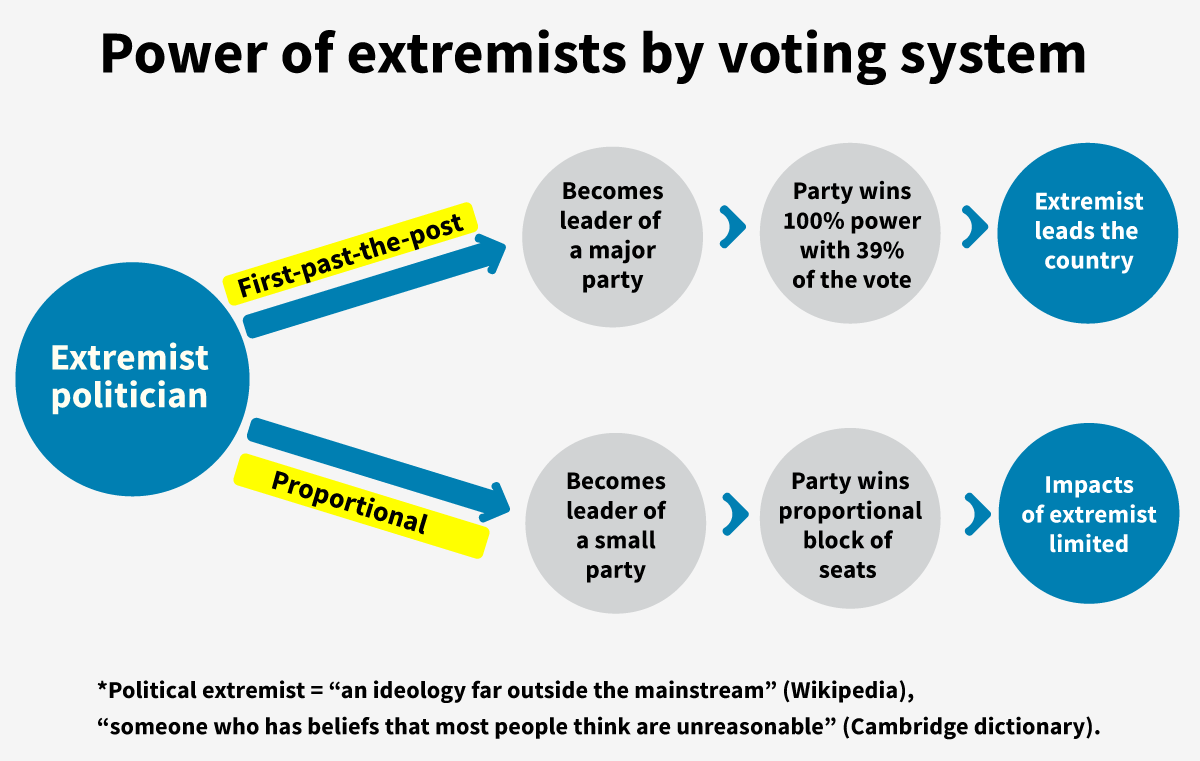

The difference between winner-take-all systems and proportional systems is in how those voters are represented in Parliament and how much influence over government policy the politicians they elect may have. In a nutshell, a proportional system tends to moderate the impact of extremist politicians.

Extremists in winner-take-all voting systems

What is a winner-take-all voting system?

Winner-take-all (non-proportional) systems are also called “majoritarian” or “plurality” systems. This includes first-past-the-post and Alternative Vote (also known as winner-take-all ranked ballot or Preferential Voting).

Winner-take-all systems aim to manufacture a “majority” government for a single party, even if that party has far less than 50% support among voters.

A small shift in the popular vote between the two largest parties can lead to a big change in the number of seats each holds in Parliament. Governments tend to flip back and forth between the two big parties: they take turns holding a monopoly on power.

How extremists become MPs in a winner-take-all system

In a country with a winner-take-all voting system, third parties and small parties usually get far fewer seats than their share of the popular vote merits―and sometimes none at all.

Most of the voters for third and smaller parties cast “wasted” or ineffective votes (they don’t help elect anyone).

For aspiring politicians with extreme political views, the best route to becoming a Member of Parliament is to run under the banner of a big tent party.

The phrase “big tent” party says it all. There can be politicians with a wide variety of views and goals―including contradictory ones―within the same party.

MPs within big tent parties are in a marriage of convenience. The fights between factions for leadership or control can be vicious.

The only thing that holds a big tent party together are the incentives of a winner-take-all electoral system, namely:

- the ability to win all the power (with a minority of the popular vote) as one big tent

- a shared animosity towards the rival big tent party

Party strategists know that in a winner-take-all system, splitting into two or more distinct parties would cost them seats and likely allow the rival big tent party to win more often.

Parties use incentives and punishments to ensure that internal differences are minimized, so the “big tent” stays together. If an MPs views are more extreme than their party’s policy platform, it may not become obvious to voters until later.

“Internal capture”: How an extremist becomes leader of the Official Opposition or even the Prime Minister

For those with extreme views and political ambitions beyond becoming an MP, the route to power is clear: sign up enough new members to win a major party leadership race.

Only about 2% of Canadians hold a membership in a political party and 1% of Canadians are very involved in volunteering for a party.

Those who vote in a party’s leadership race―particularly new party members that may have signed up to support a candidate’s position on a single issue―may not be very representative of that party’s own voters, much less most Canadians.

Once a politician wins the leadership of a big tent party in a winner-take-all system, the position of Prime Minister is within reach.

Lockwood and Lockwood (2022) describe how this this phenomenon plays out with far-right populist parties:

“In countries with plurality and majoritarian electoral systems, which tends to lead to a few (often two) large parties and majority governments, we expect right wing populists to enter governments via internal capture of the existing centre-right party. While such cases may be rare, when they do occur, we expect them to have a greater effect on all policy areas, since populists effectively capture the whole of government.”

Prime Ministers in Canada have an incredible amount of power

The concentration of power in the Prime Minister’s Office has ballooned over recent decades. As renowned Canadian political scientist Donald Savoie wrote in the 1990’s:

“Cabinet no longer operates as a decision-making body, but rather serves as a focus group for the Prime Minister.”

In 2020, his verdict was even more severe:

“Cabinet has now joined Parliament as an institution relegated to making decisions legitimate that are struck elsewhere, or in the Prime Minister’s office, a handful of courtiers. Only one brand is now tolerated: the PM brand.”

As Bakvis and Wolinetz note in “The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies”, the Prime Minister of Canada exercises “power and influence which would make many presidents jealous.”

A study of 22 OECD countries found that Prime Ministers in Canada held more power than in any other country.

National Post columnist Triston Hopper laid it out in 2018:

“Canadian prime ministers, as a rule, retain awesome amounts of personal power as compared to leaders in other Western democracies.

This is something that former Prime Minister Stephen Harper has addressed directly. In an interview last year, Harper said that even when he commanded a minority government, he had more ability to “get things done” than U.S. President Barack Obama―despite the fact that Obama’s party had control of both the Senate and the House of Representatives at the time.”

When International Strategic Analysis put together a ranking of the world’s most powerful leaders, Trudeau ranked ninth―a spot that put him ahead of literal autocrats such as Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

While part of that was due to the fact that Canadian leaders oversee a particularly large and wealthy country, what put Trudeau on the leaderboard was that his ‘hold on power’ ranked higher than almost any other democratic leader (and even a few non-democratic ones).”

Extremists in proportional systems

What is proportional representation?

Proportional representation systems create a Parliament that reflects how people voted.

That means that if a party gets 39% of the popular vote, they will get roughly 39% of the seats. Parliament generally represents the different political views in society.

No single party holds all the power unless they earn the support of more than 50% of the voters.

In countries with proportional representation, parties with values or policy goals in common usually govern together.

Over 80% of OECD countries use systems based on proportional representation.

The career path of extremist politicians in a proportional system

In systems with proportional representation, third parties and smaller parties have representation close to the actual popular support for those parties.

A party with 15% voter support will get roughly 15% of the seats.

In a country with a winner-take-all electoral system, MPs with extreme views are sitting as MPs in the big tent parties. They may hold cabinet positions. And they may even become the Prime Minister.

The difference in a proportional system is that politicians with extreme views tend to form their own party, because even smaller parties can win seats.

Examples of such parties in Europe are Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Sweden Democrats and the Finns Party.

While the views of these parties may not be shared by the vast majority of voters, their voters are given fair representation.

Having truly like-minded people within a party provides transparency for everyone.

When politicians are no longer encouraged to hide their more controversial views behind the banner of the big tent party, voters know exactly what candidates stand for. And the voting public can hold the bigger parties accountable if and when they choose to collaborate with the smaller ones.

The roles and effects of small far-right parties in Parliament

The approach to far-right parties in Parliament varies by situation, with a wide range of responses from exclusion, to debate, to tolerance, to constructive cooperation.

If a party’s views are too extreme, other parties generally refuse to work with them to avoid becoming associated with those views. The other parties may band together as necessary to ensure an extremist party is not included in a governing coalition.

Beyond this, the mainstream parties may work to deny the extremist party much influence in Parliament. Political scientists refer to this practice as drawing a “cordon sanitaire” or protective line.

For example, Alternative for Germany (AfD) has received anywhere from 4.6% to 12.7% of the federal vote in the past decade. AfD has seats in the federal parliament and 16 state legislatures in Germany. Of those 17 governing coalitions, including at the federal level, all 17 excluded the AfD.

Similarly, the Sweden Democrats have received anywhere from 12.9% to 17.5% of the federal vote in the past decade, but have never been part of a government beyond the municipal level. They were long shunned by other parties, although this has been changing in recent years as one of the major parties was willing to enter into a discussion with them.

In many cases, however, the way that mainstream parties deal with far-right parties is not so black and white, particularly when the far-right party has a variety of policy positions and represents the views of a significant number of voters.

Efforts by the big parties to exclude far-right parties from meaningful participation in Parliament may do more to help those parties cast themselves in a victim role and inflame the real tensions in society that fuel the party’s rise in the first place.

Many countries with proportional representation have a strong history of inclusion and consensus-based politics. They demonstrate that small far-right parties can sometimes play a constructive role in Parliament, particularly when collaborative work across party lines is done on committees.

As Poyet and Runio note in their study of the impact of the (populist) Finns Party on Parliament, the difference between winner-take-all and consensus democracies is pronounced:

“Consensual democracies arguably have ‘working parliaments’, where scrutiny in committees is more important than plenary debates, with MPs concentrating on legislative work instead of grand debates on the floor.

Majoritarian regimes in turn tend to have ‘debating parliaments’, where the plenary offers an ‘arena’ for more adversarial politics.

In working parliaments, political parties across the board are thus more used to working together…”

In most cases, if an extreme party even wants to move beyond being a protest party (and being treated as such), then they must moderate their positions and behaviour.

The example of the New Zealand First Party, a small “nationalist, populist” party with views across the political spectrum but restrictive views on immigration, is instructive.

In 2005, they partnered with Helen Clark’s Labour government. In 2017, they became partners in a coalition government with Labour led by Jacinda Ardern.

Referring to the smaller party in the government, “the tail did not wag the dog – it barely wiggled”. New Zealand First was not able to enact its more “radical” policies. Rather, they played a constructive role, and the policies implemented by the coalition government enjoyed wide support.

Moderation is exactly what the Finns Party did when they were included in a governing coalition from 2015–2017. As the researchers concluded, their effect on Finland’s cooperative-style Parliamentary work was “minor”:

“The populists have brought more confrontational elements to the debates but seem content operating within the established institutional constraints. …

Populist parties are often leader-centric, but behind hawkish party chairs, there can be more constructive MPs whose agenda and behaviour hardly differs from the MPs of the ‘old parties’.”

Canadians are right to be concerned about the potential impacts of extremist politicians. What has happened in other countries could happen here because first-past-the-post leaves us vulnerable. We should consider upgrading our electoral system to one that is proportional—sooner, rather than later.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES ON CLOSELY RELATED TOPICS

Fact Check: Fringe Parties

Concerns that an abundance of “fringe parties” would win seats with proportional representation in Canada are unjustified. In the last few federal elections, all 15-20 fringe parties put together didn’t get 1% of the vote. Models of proportional systems recommended for Canada tend to be designed with a fairly high threshold for representation, meaning that it would be difficult for very small parties to get a seat. Countries already using these types of systems don’t tend to have a greater number of political parties with seats, on average, than Canada has now.

Research: Proportional representation reduces partisan hostility among voters

“Polarization”, the “us vs them” sentiment in politics, where people feel hostile towards those on the “other” side, is a growing concern. PR may help reduce these feelings of partisan hostility. Research has found that people in countries with PR felt warmer towards any parties that had been in a coalition government with their preferred party anytime over the previous 15 years. This warmer feeling remained even if the parties that had been in a coalition together were ideologically far apart.

Research: Proportional representation reduces polarization

Research has found that voters in countries with winner-take-all voting systems perceive their country’s political parties to be further not only from one another, but also from themselves. In other words, winner-take-all systems are more polarized. Rodden (2018) concludes: “Proportional representation brings a powerful advantage: it can allow the political system to absorb the rise of new issue dimensions, from environmentalism to women’s rights to nativism, without the issue-bundling that facilitates all-encompassing American-style polarization.”

Research: Proportional representation reduces hostility in Parliament

Nemoto and Pinto (2019) studied the nature of political discourse in the New Zealand Parliament before and after proportional representation was adopted in 1996. Analyzing 821,442 parliamentary speeches by MPs from 1987 to 2016, they found a marked decrease in anger and hostility in MP’s speeches overall after 1996, most significantly in the tone of ruling party MPs towards smaller parties who might one day be coalition partners with them.

Research: Proportional representation protects climate policy from the influence of the far right

Lockwood and Lockwood (2022) found that countries with proportional representation (PR) voting systems are better protected against the threat of having climate policy reversed by right wing populists than countries outside the EU with winner-take-all systems such as Canada, the USA and Australia. In countries with proportional representation, far-right parties had no significant effect on climate policy.

Blog: Economist Democracy Index and “Freedom Convoy” challenges Canada to build an inclusive democracy―or slide into American-style problems

The Economist’s latest Democracy Index report and the disruption caused by the Freedom Convoy warns of Canada’s slide into US-style political problems.