COVID-19 has been a tremendous boon to the popularity of most political leaders, and it’s leading to some cheap, partisan ploys. Who could let such unexpected good fortune go to waste?

For those elected to minority governments prior to COVID-19, the temptation to call a snap election and try to “upgrade” to a majority has become well-nigh irresistible.

Why bother with the headache of cooperation in a minority government when you can seize all the power with as little as 39% of the vote?

A snap election worked for Harper in 2011, when, after 2 years of minority government, he asked voters for a “strong, stable majority” and he got it—with 39%.of the vote.

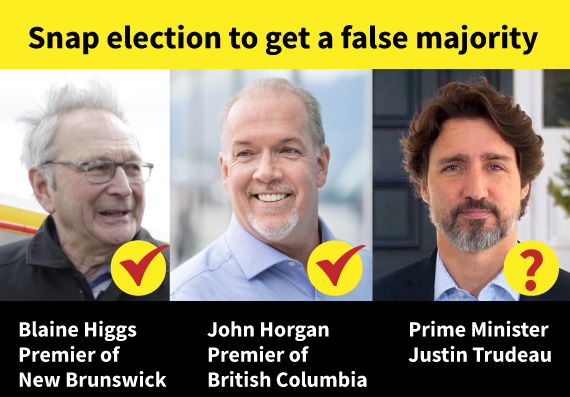

It worked for Blaine Higgs just last week when he swapped in his high-functioning minority government for a shiny new majority. Again, with just 39% of the vote. One of the best examples in Canada of highly effective all-party cooperation to tackle COVID-19 fell victim to naked political opportunism.

Polls indicate the same roll of the dice is probably going to work for John Horgan, who is currently projected to win 68% of the seats with only 44% of the vote.

Most BC voters probably don’t want an early election—during a pandemic. Horgan just unilaterally tore up his cooperation agreement with the Greens, despite Greens imploring him to continue working together. Sadly, in our electoral system, he’s more likely to be rewarded than rebuked.

Federally, numerous columnists have pointed out that Trudeau appears to want an election only one year into his minority government—as long as he can blame the other parties for it. If we avoid a federal election this fall or next spring, it may be only because he hasn’t found a way to do that convincingly.

Unlike Higgs and Horgan, Trudeau’s ratings have taken a modest beating in the polls thanks to the WE scandal. The majority power he craves is likely with a snap election—but not a slam dunk.

It’s the system

In each of these disheartening scenarios, Canadians must remember that it’s not the leaders, and it’s not the party backroom. It’s the voting system.

The carrots and sticks of first-past-the-post define how the game is played. It’s only logical for leaders who are up in the polls to gamble on an election.

Leaders hovering around 40% know a COVID election is a game they’re almost sure to win. To miss the moment can mean consequences that are disproportionately cruel. In a first-past-the-post system, a small drop in voter support often means being tossed out on your ear―and who knows how long the pandemic-induced political honeymoon will last.

Voters want democracy that works in the public interest

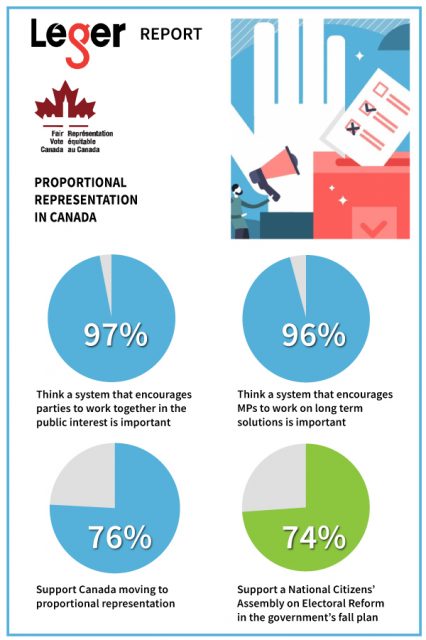

Last week’s national poll by Leger showed that a whopping 97% of Canadians think parties working together in the public interest is important to improving democracy. They want action on electoral reform.

For those who value minority governments, the cold reality is that with first-past-the-post, parties only work together to the degree they must when they have no other choice.

And that is the difference in countries with proportional representation (PR). 40% of the vote gets 40% of the seats. The winner-take-all game of skewed numbers that drives our politics simply does not exist.

With PR, parties who trigger early and unnecessary elections may well be punished by voters—not rewarded by the system! So, they rarely do it.

With proportional representation, cooperation is practically inevitable since voters very rarely give a single party more than 50% of the vote. On any measure that Canadians hold dear—health, environment, economy—research shows that the voters are better off for it.

76% of Canadians agree: It’s time to change the game.