Speculation is rampant that the NDP may end their Confidence and Supply Agreement (CASA) with the Liberals. If the NDP pulls the plug, it will bring the inherent instability of the Liberal minority government into stark relief, and the talk of an early election will heat up.

When the NDP and Liberals formalized their CASA in 2022, some commentators didn’t see much difference between the outcome of their agreement and what Canada would get with proportional representation.

Yet if we scratch below the surface, it becomes clear that the differences are profound.

Who is at the table and what negotiating power do they have?

Let’s start with the obvious. With first-past-the-post, election results can be massively distorted. Parties negotiating any agreement in a first-past-the-post system are often doing so from a position of having obtained far more or far less seats than their popular support would warrant. Voter intention is misrepresented before negotiations even begin, to the benefit of the larger, or most regionally concentrated, parties.

Government stability and party incentives: first-past-the-post vs PR

The Liberal-NDP CASA began with the best of stated intentions: to promote stability and get things done for Canadians. While the agreement was a significant milestone in terms of cooperation, its relative longevity has been entirely due to crude political calculations.

With the Liberals so unpopular in the polls and the NDP chronically disadvantaged by first-past-the-post, neither has had any incentive to send Canadians back to the polls.

Generally speaking, minority governments elected by first-past-the-post rarely last longer than two years. The parties who benefit disproportionately from our electoral system know that if they trigger an early election at an opportune time, they can transform their minority government into a “majority” with less than 50% of the vote. The most recent elections in New Brunswick and BC are typical examples of this opportunism.

Doug Ford, despite having a majority government, is currently speculating about calling an early election to take advantage of “vote splitting” in a first-past-the-post system while his party is still high (around 40%) in the polls.

Research shows that governments in countries with proportional representation, where no party can win all the power with a minority of the vote, are inherently more stable.

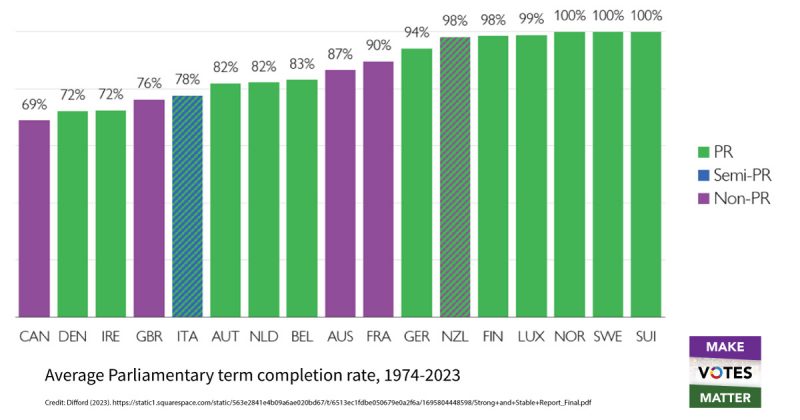

Difford (2023) looked at the term completion rate for every parliament dissolved within the last 50 years in our 17 western democracies. This is a measure of how long a parliament lasted relative to its term limit. For example, a parliament that could have sat for four years but only sat for three would have a term completion rate of 75%. He concluded:

“PR countries do not have earlier elections than those that use non-PR voting systems. Indeed, on average, it is FPTP users like Britain and Canada who have some of the worst parliamentary term completion rates among western democracies.”

Since New Zealand adopted proportional representation in 1996, every government except one has lasted for a full term (and even the lone early election was just three months early).

Canada, by contrast, has had four early elections during the same time period, most called years before the government hit the four year mark.

More meaningful cooperation right across the political spectrum

The most common type of government in countries with proportional representation are majority coalitions. This means more than one party has Ministers in the Cabinet. Parties craft government legislation together.

The CASA between the Liberals and NDP was much more limited. Essentially it boiled down to regular meetings between party representatives plus the Liberal government agreeing to follow through with a few very specific NDP priorities in exchange for the NDP ensuring that the Liberals could pass their budgets and survive any confidence votes.

Cooperation in countries with proportional representation goes beyond coalitions of parties on the right alternating with (and opposing) coalitions of parties on the left.

Although these kinds of coalitions are common, leading to enduring relationships between parties with similar values, formal coalitions and more informal collaboration in Parliament can span the political spectrum.

Cooperative governments which bridge political divides have proven successful for years in Germany, the largest economy in Europe. Currently, Germany’s three-party coalition government is collaborating with the mainstream conservative opposition party to safeguard Germany’s top court from the risk of partisan manipulation and extremism.

In Ireland, the two traditional centrist governing parties―historic political rivals for a century―formed a 5-year coalition with the Green Party that has lasted a full term. Ireland leads the OECD in labour productivity and has the world’s most satisfied voters.

In Denmark, after the left-leaning block won an outright majority of seats and possibility of a second government on the left, Denmark’s Social Democrat leader chose to form a centrist coalition with parties on the centre right instead.

In general, parties are more likely to work together on important issues in the public interest, rather than polarizing those issues for short term political gain.

This kind of cooperative politics was on full display in 2020, when Denmark passed the strongest climate legislation in the world. The legislation was the result of collaboration between nine parties, including conservatives.

As Denmark political scientist Rune Stubager explained:

“We have a culture of negotiations and broad agreements. It’s something people like. They think reason should prevail and parties will come together and do what’s best for our societies.”

With the arguable exception of the Pearson years,, the closest we’ve come to that kind of cross-party cooperation in post-WWII Canada was a fleeting moment when the COVID pandemic hit in spring 2020.

With a winner-take-all system, it can take a life-threatening national emergency to temporarily produce the kind of dialogue between parties in the public interest that is routine in many countries with proportional representation.

More policy stability: less extreme policy lurches

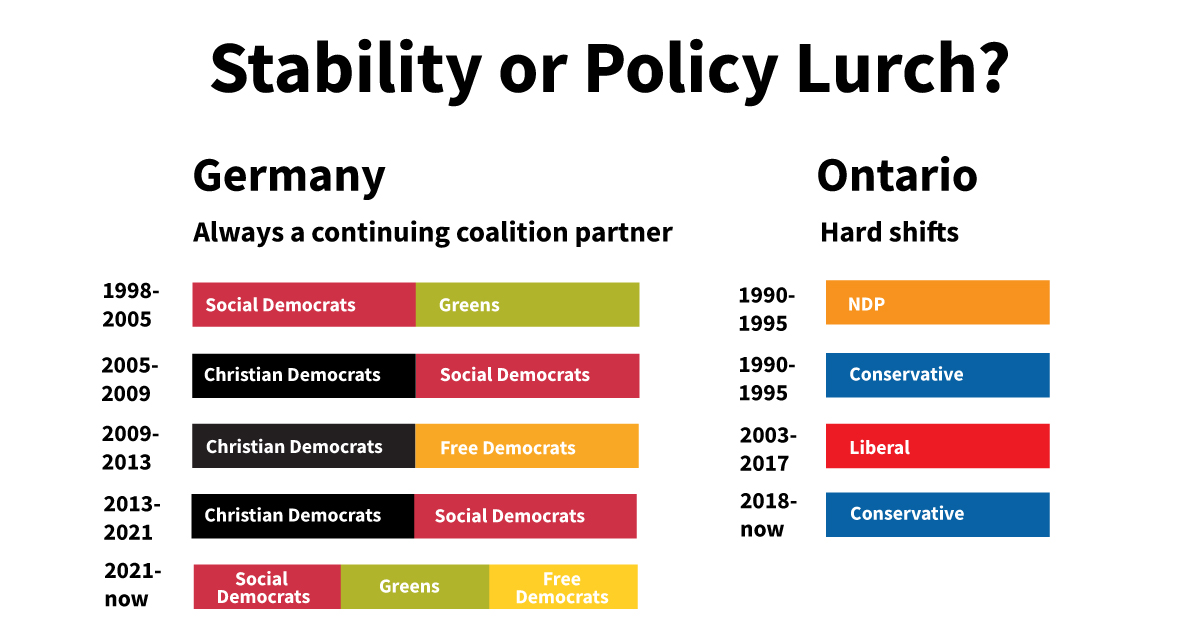

One of the consequences of any winner-take-all voting system is severe policy lurch: abrupt policy swings when one government is replaced with another. Programs and policies brought in by one false majority government may be dismantled and reversed by the next false majority government.

Examples abound: When the Liberals were handed a majority in 2015 with 39.5% of the vote, they immediately set about undoing policies from the Harper years. When Doug Ford came to power in Ontario 2018 with 40% of the vote, he began reversing policies from the Wynne years.

Proportional representation can reduce the degree of policy lurch because laws cannot be forced through (or repealed) by a single party representing only a minority opinion. With PR, all legislation must have the support of multiple parties who represent a real majority of voters―and public opinion as a whole doesn’t tend to swing violently.

When a new government is formed, even when it represents a significant shift in direction and a change in leading parties, it often includes a continuing partner, as has been the case in Germany.

A culture of collaboration promotes greater policy stability that can improve investor confidence and make longer-term planning more successful.

Less polarization and less hostility

When New Zealand adopted proportional representation, research looking at 841,442 speeches in the legislature showed that PR helped reduce the level of toxic rhetoric. Parties who knew they might be future coalition partnersused less aggressive language towards each other in Parliament than they did when New Zealand used first-past-the-post.

More importantly, when cooperation and finding common ground is normalized and elections are not a zero-sum game, it can help reduce polarization and dial down hostility among the public.

On this point, the research is clear:

- Proportional representation mitigates issue-based and identity-based polarization.

- In democracies with proportional representation where coalition governments are the norm and often cross the political spectrum, citizens feel more warmly towards parties they didn’t vote for when those parties have been in a coalition with their preferred party anytime in the past fifteen years—even when those parties are ideologically far apart.

When the public is used to seeing their preferred party working with parties across the spectrum, it changes their attitudes.

The bottom line is that incentives produced by electoral systems―and the political cultures they help create―matter. The transient and limited degree of cooperation we’ve seen between the NDP and Liberals with the CASA, while a step in the right direction, doesn’t reflect the breadth or depth of cooperation that is often seen in countries with PR.

In today’s hostile political environment, when a single party can gain control with barely more than a third of the popular vote, even the most popular policies are at risk.

If we want stable, long-lasting, productive governments that accurately represent Canadian voters, we need proportional representation.