Denmark had an election yesterday.

The contrast to Canada’s last election couldn’t be more stark. It isn’t just in the numbers―it’s in the politics.

In Canada, with first-past-the-post, the pursuit of power drives the agenda.

Minority governments are tenuous. They last until one party believes they can seize all the power with 39% of the vote. They want to gain complete control of Parliament.

Most of Canada’s minority governments have lasted about two years.

In Denmark, by contrast, elections occur predictably every 3 to 4 years.

With proportional representation, no single party has been handed all the power in Denmark since 1909. The last time Denmark had a government that lasted only two years was back in 1979.

Parties in Denmark have learned to work together―and the voters expect them to do so.

An informed and engaged electorate

Unlike in Canada, where the Prime Minister attends only two debates with the other party leaders, voters in Denmark can watch 13 televised debates. This gives voters a deeper understanding of the policies each party is offering.

Denmark’s media performs at a high or outstanding level for freedom of expression, political independence, and social inclusiveness.

A 2022 study looking at how Danish media covered elections concluded that Denmark’s media gives fair treatment to the concerns of the elites and the public.

Denmark’s 2022 election: every voter really mattered to the outcome

Voter turnout in Denmark’s election was 84.1%.

Canada’s last federal election? 62.3%

Canadians elections are often characterized by divisive fear mongering and “horse race” politics.

An exit poll conducted immediately after the last election showed a whopping 49% of Canadian voters were using their votes to stop a party they dislike, rather than to elect a party they support.

In Denmark, voters could vote for the parties and candidates they believed in―knowing their votes really counted.

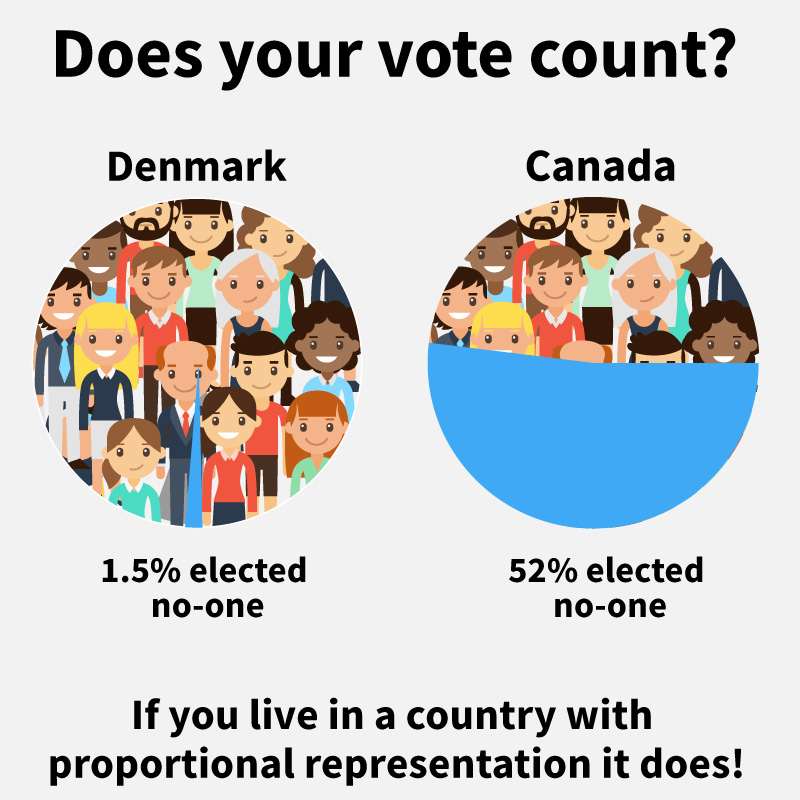

98.46% of Danish voters cast a ballot that helped elect an MP.

In Canada’s last federal election, the majority of Canadians (52%) cast ballots that made no difference at all.

“The youth vote is serious”

Becoming politically informed and engaged starts early in Denmark. The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study, which looked at democratic literacy among students in 38 countries, ranked Denmark at the top.

Politicians make substantial efforts to reach young voters. Turnout among 18-year-olds in Denmark’s 2019 election was a whopping 85.1%. In Canada’s 2021 election, turnout among voters 18–24 years old was a pathetic 46.7%.

As Youth Journalism International reporter Amy Goodman observed about Denmark: “The youth votes mean something, and the politicians know it.”

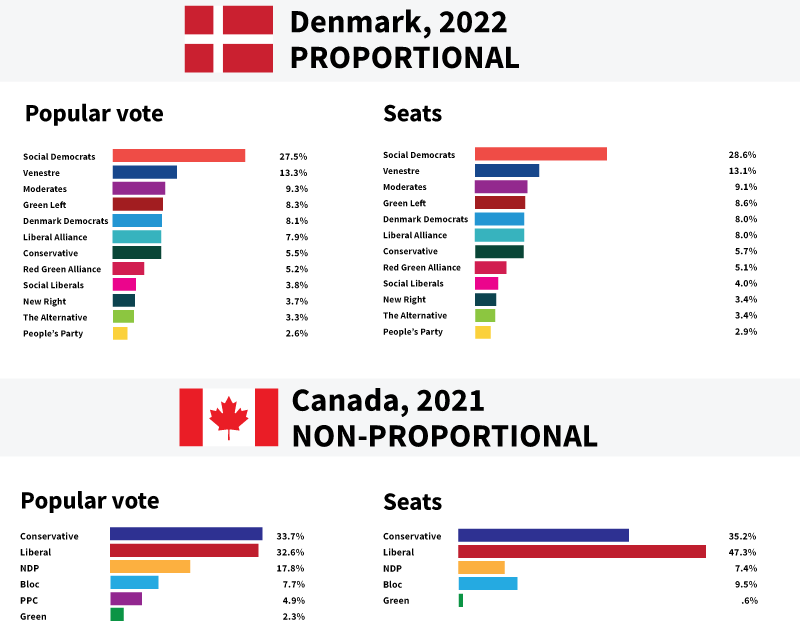

Most importantly, in Denmark, voters got what they voted for.

Canada’s 2021 election results were the usual lopsided distortions of first-past-the-post. In Denmark, the Parliament reflects what voters wanted:

Cooperation is an integral part of Denmark’s system―and it drives results

Not only is representation fair, decision-making in Denmark’s next Parliament will take into account what more people want.

Denmark’s politics has always been dominated by the spirit of collaboration between parties. As Danish political scientist Rune Stubager explains:

“Danish politics in general is a very consensual affair. Most of the legislation is passed with super majorities or with parties from other blocs.”

Even before the election campaign began, Social Democratic Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen was clear that after the election, she hoped to reach across the aisle and form a broader coalition:

“With the difficult times we live in and the hardships the world is facing … the time has come to test a new form of government”.

Today the final results were announced, and Mette Frederiksen’s left-wing bloc has won an outright majority of seats.

Despite securing its best result in decades and winning the right to govern with the support of like-minded political allies, Frederiksen’s government has resigned in order to form a broader coalition.

She called on all the parties to “seek cooperation” and promised to do everything possible to form a government that spans the political spectrum:

“I’m very, very happy,” Frederiksen said as she arrived at parliament after midnight on Wednesday. When asked if she would still seek a broad-based coalition, she replied in the affirmative, saying “we will do all we can to realize it.”

With first-past-the-post in Canada, the opposite kind of politics usually rules.

Successful parties and their strategists don’t want to work together. They crow loudly about defeating their rivals. They massively exaggerate the popularity of their parties and the strength of their win.

On election night In Canada, Gerald Butts (former Principal Secretary to Justin Trudeau) bragged about “vote efficiency” on Twitter, pointing out how the “geniuses” at the data company hired by the Liberals had excelled at micro-targeting a handful of voters in swing ridings.

Justin Trudeau thanked Canadians for having (again) given him “a clear mandate”—ignoring the fact that the Liberals won a mere 32.6% of the popular vote.

In Ontario, Doug Ford said he couldn’t have been more pleased with the first-past-the-post system on election night. He praised the 18% of eligible voters who handed his party a “majority”:

”I think this system has worked for over 100 and some odd years and it is going to continue to work that way. But I’m just so proud of the coalition (that voted PC).”

Cooperation gets results for people

Cooperative governments which include parties that span the political spectrum have proven successful for years in Germany, the largest economy in Europe.

In Ireland, the two traditional governing parties―historic political rivals for a century―formed a 5-year coalition with the Green Party to strengthen Ireland’s economic, social and environmental future. Ireland leads the OECD in labour productivity and has the world’s most satisfied voters.

In Denmark, cooperation between parties is part of a culture of trust that makes lasting and transformational progress possible.

For example, innovative and effective programs for “aging in place” continue to evolve in response to public demand. Institutional long-term care homes, still common in Canada despite their unpopularity, were banned in Denmark in 1984. Meanwhile, Canadian governments spin their wheels and let hopelessly negligent providers off the hook.

A culture of political collaboration means parties can forge lasting agreements on issues that have become dangerously polarized in countries with winner-take-all voting.

This kind of consensus politics was on full display in 2020, when Denmark passed the strongest climate legislation in the world. The legislation was the result of collaboration between nine parties, including conservatives.

In Denmark, voters and parties expect a strong, inclusive democracy―and they get it.

As Denmark political scientist Rune Stubager says:

“We have a culture of negotiations and broad agreements. It’s something people like. They think reason should prevail and parties will come together and do what’s best for our societies.”

Isn’t that what we need in Canada?