What about political stability?

Stated by: Bill Tieleman, spokesperson for the official NO campaign, Globe and Mail, July 1, 2018.

NOTE: The claim of instability is often made in connection with the economy. For a Fact Check on proportional representation and economy, see here.

Fact Check Summary

This claim is false. Elections are no more frequent with proportional systems, although changes in which parties form the government may be. Stability of policy may be improved with proportional representation.

What do people mean by “stability”?

Political stability can often refer to:

- Frequency of elections

- Changes in the parties that form the government (which does not necessarily coincide with an election)

- Stability measured by the Fragile States Index (12 measures)

- Policy stability – the degree to which policy changes when governments change

See more on each of these areas below.

No difference between electoral systems in terms of frequency of elections

a

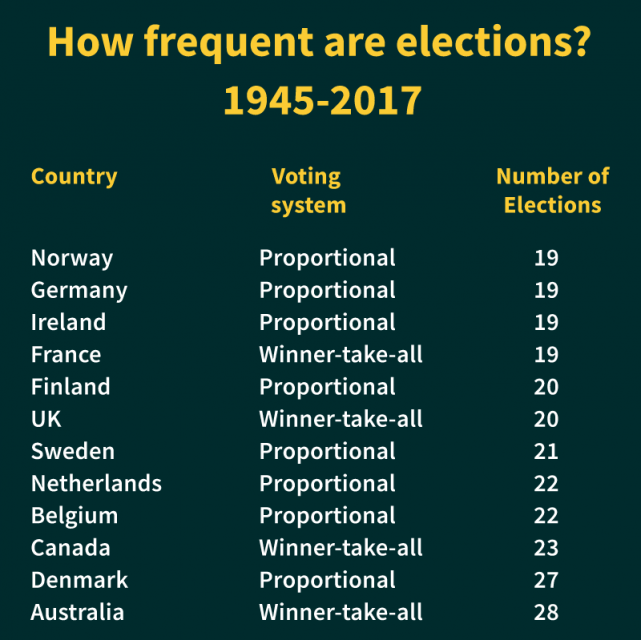

Research shows little difference between OECD countries using proportional or “winner-take-all” systems. Looking at elections from 1945 to 1998, Pilon (2007: 146-154) calculates that countries using FPTP averaged 16.7 elections, while countries using proportional systems averaged only 16.0 elections. There is no significant difference between the two.

a

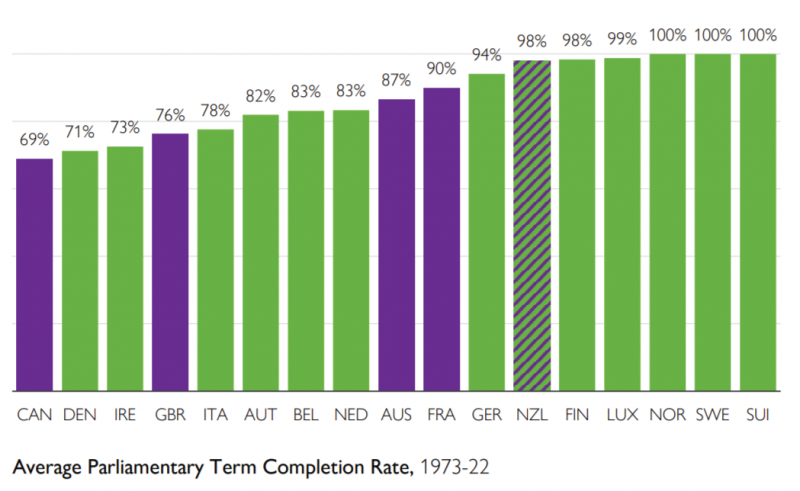

Difford (2023) looked at the term completion rate for every parliament dissolved within the last 50 years in our 17 western democracies. This is a measure of how long a parliament lasted relative to its term limit. For example, a parliament that could have sat for four years but only sat for three would have a term completion rate of 75%. Difford found that “PR countries do not have earlier elections than those that use non-PR voting systems. Indeed, on average, it is FPTP users like Britain and Canada who have some of the worst parliamentary term completion rates among western democracies.” (See figure below. Credit: Difford).

With proportional representation, governments (cabinet composition) can change between elections

Most OECD countries with proportional systems are governed not by minority governments, but by majority coalitions of two or more parties representing over 50% of voters, with different parties holding Ministerial positions.

Sometimes between elections, there is a change in the parties that are part of the governing coalition. For example, a smaller party may leave the coalition. When this happens, it does not necessarily require another election. This is closer to what we would call a “cabinet shuffle” in Canada.

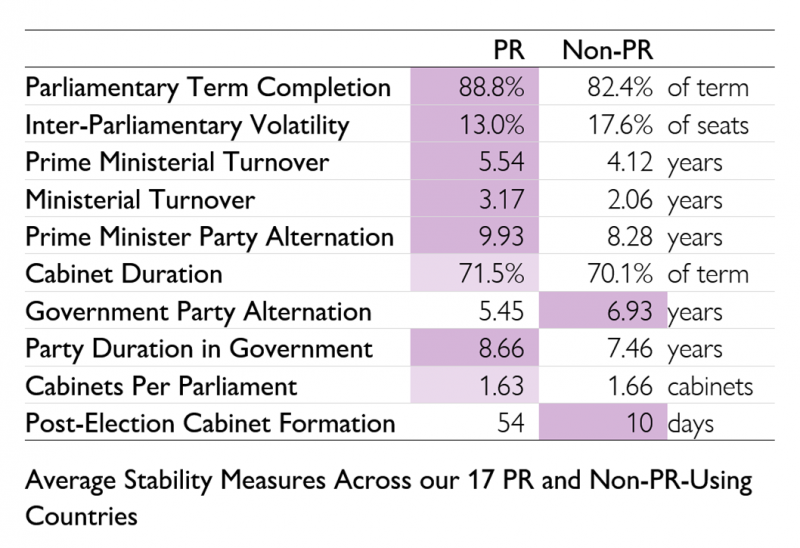

Difford (2023), looking at 17 established western parliamentary democracies from 1973 to 2022, found that “countries with the most durable cabinets are largely those that use proportional representation.” He also found that on eight of the ten measures of political stability, including , proportional democracies, on average, outperform those that use majoritarian systems. See figure below (credit: Difford).

Lijphart (2012), on the other hand, in his book “Patterns of Democracy” looking at looking at 36 countries over 55 years, found the average cabinet duration is slightly shorter in countries with proportional systems. He observes:

It is actually easier to change a government in consensus democracies than in majoritarian democracies, as shown by the shorter duration of cabinets. Changes in consensus democracies tend to be partial changes in the composition of cabinets, in contrast with the more frequent complete turnovers in majoritarian democracies

.

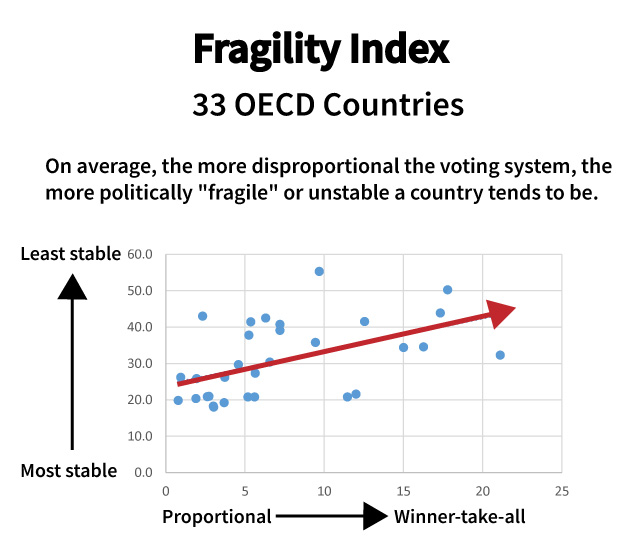

The Fragile State Index shows winner-take-all systems are more unstable

Every year, the Fragile States Index ranks countries for fragility. The index looks at 12 measures of stability. The index indicates that nine of the top ten most stable countries in the world use proportional representation. The more disproportional the electoral system is, the higher the instability.

a

Proportional representation means greater policy stability

Policy lurch refers to abrupt policy swings one government is replaced with another. Programs and policies brought in by one government may be dismantled and reversed by the next government.

According to Lijphart, policy lurch is “a serious problem from which majoritarian systems suffer”, first identified by S.E. Finer, as the main thesis of his 1975 book. Proportional representation can mitigate policy lurch, because laws have the support of multiple parties who represent a real majority of voters. According to Lijphart:

“Policies supported by a broad consensus of people are more likely to be carried out successfully and to remain on course than policies imposed by a “decisive” government against the wishes of an important sector of society.”

Lijphart cites Knutsen’s (2011) conclusion that higher rates of economic growth found in countries with proportional systems could be attributed to the focus on nation-wide economic growth over a focus on resources for individual districts in winner-take-all systems.

Similarly, Nooruddin’s (2011) study of economic volatility and electoral systems found that coalition governments produced less economic volatility due to more stable economic policy. He notes:

“When a single party controls all the levers of the legislative process, it is better able to enact policies closer to its ideal point. The resulting policy might in fact be the preferred outcome for economic agents too (for instance, if the government in question favors a business-friendly policy regime), but the government can not guarantee that future governments will not reverse course should the opposition win. In this case, even if economic agents respond by investing in the country, they will remain wary of future policy change, and therefore forgo more irreversible investments .

Using cross-national time-series data from over 100 developing countries, that even after controlling for plausible alternative political factors and for theoretically-relevant economic factors, coalition governments in parliamentary democracies have higher growth rates than other forms of government, and such governments experience lower growth-rate volatility.”

Nooruddin also found that business judged countries run by coalitions to be more stable:

In a World Bank survey of firms across the world, I find that firms located in countries governed by parliamentary coalitions are less likely to perceive policy uncertainty to be a major obstacle to their businesses, and more likely to consider opening a new establishment in the near future. Similarly, such countries generate higher rates of private saving and induce lower levels of capital flight.

References

Difford, Dylan (2023). Strong and Stable. A comparative analysis of the supposed link between voting systems and political stability.

Fund For Peace (2018). Fragile States Index, Global Data. http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/data/

Pilon, Dennis (2007). The Politics of Voting: Reforming Canada’s Electoral System. Edmund Publishing.

Knutsen, Carl (2011). “Which Democracies Prosper? Electoral Rules, Forms of Government, and Economic Growth.” Electoral Studies 30: 83-90.

Lijphart, Arend (2012). Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in 36 Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale Press.

Nooruddin, Irfun (2011). Coalition Politics and Economic Development. Credibility and the Strength of Weak Governments. Cambridge University Press.