Doug Ford’s move to concentrate power with “strong mayor” system a step backward for local democracy

Provincial and federal politics suffers from an overwhelming and stifling concentration of power in the leader’s office.

With decisions cooked up by a few unelected party hacks around the Premier or the Prime Minister, there’s nothing for most MPs or MPPs to do but sell (or oppose) decisions they had no say in making.

If Doug Ford gets his way, this curse of federal and provincial politics could be coming to city councils across Ontario.

At just the moment when even the Economist’s Democracy Intelligence Unit is warning about Canada’s slide towards US-style political problems, Ford seems hell bent on Americanizing our municipal politics.

The plan to strip local city councillors of decision-making power and hand it to a “strong mayor” is not something Ford campaigned on before he won his latest “majority” (with the backing of 18% of eligible voters).

Just like Toronto city council was blindsided when Ford unilaterally slashed the number of councillors from 47 to 25 in 2018, the “strong mayor” plan doesn’t seem to be something city councils were asking for, either.

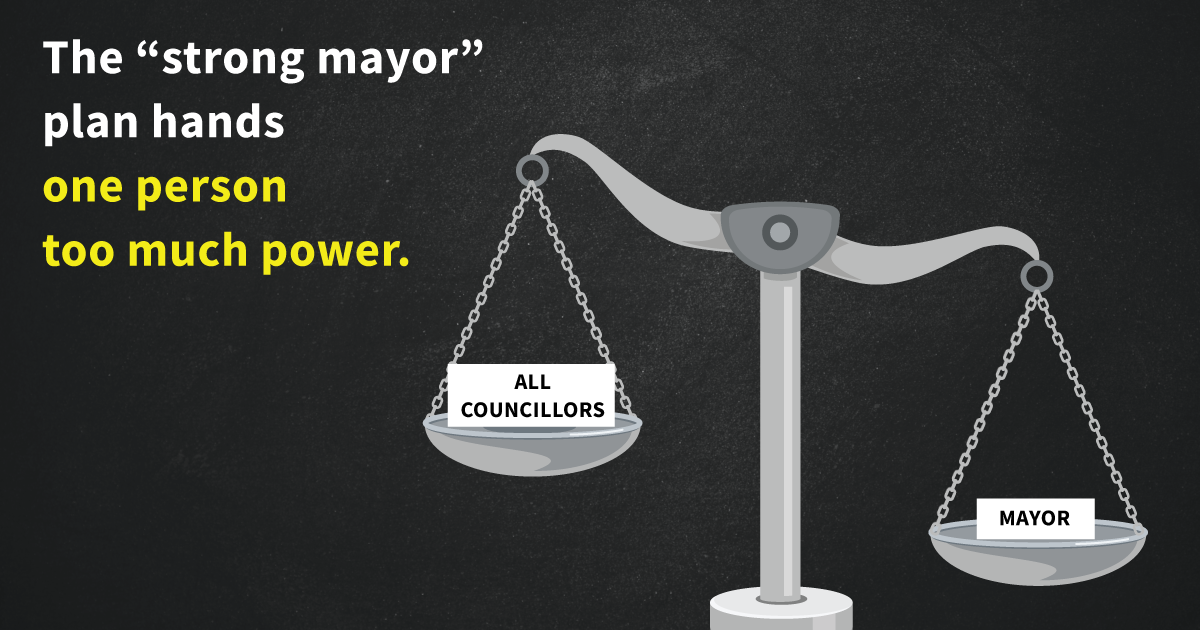

It’s easy to see why: on the most important pieces of policy, like the budget, it would take a vote of two thirds of councillors to override a decision by the mayor.

That’s a strong mayor, indeed.

Who benefits from the “strong mayor”?

It’s dubious whether a “strong mayor” has anything to do with what voters want or need from their local democracy.

According to a 2019 study by Leger Research and the Argyle Group, strong majorities of Canadians said that having a relationship with their local government made them more likely to vote in municipal elections, to feel a sense of belonging, and support local government decisions.

Anyone who’s ever read the research by the Samara Centre on Democracy – which interviews former backbench MPs, who talk candidly talking about just how powerless they were – is painfully aware of how vast the chasm is between ordinary voters and those at the top.

With only one third of Canadians believing they have any influence on city council decisions now, Ford’s plan could make the problem even worse.

Any plan that threatens to put even more distance between citizens and decision-makers, by concentrating the power in one personality rather than their representatives across the municipality, is likely to erode trust and lead to even more disengagement.

Voters could be forgiven for asking themselves:

Why vote for a local councillor when our local councillors are little more than a focus group for the mayor?

Currently, at least some voices from diverse points on the political spectrum are represented in the city council rooms where decisions are made.

The vote of a city councillor can also be influenced by passionate and informed pleas by local citizen delegations. And they often are.

How can the opinion of one person possibly be more democratic?

The “strong mayor” may be the lobbyist’s dream. After all, it’s easier to get a single individual in your pocket than to win a majority of the city council’s support for your plan. It’s no surprise that US research analyzing corruption in municipal politics showed that cities using the “council-manager model” (like Toronto) had 57% less corruption than those with a “mayor-council” model (which included cities with “strong mayors”).

While municipal democracy remains in deep need of improvement, it’s the perception of a more human, down-to-earth democratic process on city councils that is probably the reason why Canadians hold their municipal city councils in higher regard than other levels of politics.

In times like this, it makes you wonder who those wanting to force a strong mayor system on Ontario cities are really working for.