Canadians’ deepest fear about the future

If you watch the news, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the biggest fear that most Canadians have about the future is the housing crisis. Or the healthcare crisis. Or, especially, the affordability crisis.

There’s no doubt that the painfully high cost of living is top of mind.

But when EKOS asked Canadians what their deepest fear for Canada’s future was, it wasn’t the price of groceries, health care, housing or even climate change. Canadians’ greatest fear about the future was “growing political and ideological polarization.”

Polarization.

Toxic, divisive politics that pits “us” against “them”, neighbour against neighbour.

This kind of polarization goes well beyond disagreements over issues, which will always exist and are part of a thriving democracy.

The kind of polarization of deep concern is what researchers refer to as “affective polarization”. It’s a mean-spirited view of others in a different “camp” that’s often driven by blind partisanship. Journalist Justin Ling describes this kind of polarization as the division of Canadians into “agitated clusters of comforting rage”.

When partisan leaders act as if those in other parties are dangerous, morally bankrupt or stupid, that kind of politics eventually impacts how we see each other as human beings.

While Canadians are worried about many important issues, at a deeper level we’re concerned about the ability of a more polarized political system to solve them.

Worrying signs that Canadians’ fears are justified

In 2022, Canada’s downward slide on the Economist’s Democracy Index prompted them to ask:

“Is Canada becoming more like America? Canada’s worsening score raises questions about whether it might begin to suffer from some of the same afflictions as its US neighbour…”

A new report by Justin Ling, Far and widening: The rise of polarization in Canada, concluded that polarization is growing in Canada.

The researchers engaged 1600 young adults aged 18–35 in discussion roundtables across the country and an in-depth survey. They found that 44% of young adults believe the political stability of Canada is threatened by the political division of its people.

Instead of incentivizing political leadership to turn down the temperature, our winner-take-all system has trapped us in a vicious feedback loop. As the report notes:

“Parties see a benefit in stepping up the demonization of each other…. They know this polarization exists and they see a benefit in exploiting it.” This polarization “resembles the growing mutual hostility Democrats and Republicans hold towards one another in the United States.”

MPs quoted in the report explained: “Parties are whipping up anger and distrust amongst their core supporters for money. Those supporters are becoming increasingly fervent in their beliefs, distrustful of rival parties and demanding of ideological purity…. The party must in turn become more confrontational and dogmatic.”

Imploring political leaders to do better―when the system rewards them for demonizing partisan opponents―just isn’t working.

For a better kind of politics, we urgently need electoral reform

Those wondering what can be done to turn the tide on hostility and polarization should heed the research:

Consensus-based political institutions that use proportional representation have lower levels of partisan hostility and identity-based, affective polarization.

As Somer and McCoy (2018), noted:

“The most extreme cases of polarization… emerge in contexts of majoritarian electoral systems that produce a disproportionate representation for the majority or plurality party.”

Institutional design and polarization. Do consensus democracies fare better in fighting polarization than majoritarian democracies?

Kamil Bernaerts, Benjamin Blanckaert & Didier Caluwaerts (2023) Institutional design and polarization. Do consensus democracies fare better in fighting polarization than majoritarian democracies?, Democratization, 30:2, 153-172.

Looking at 36 democracies from 2000-2019, the researchers concluded:

“Institutions matter for polarization, and do so strongly… Countries with consensus institutions, and in particular proportional electoral systems, multiparty coalitions and federalism, are related to lower levels of both issue-based and identity-based polarization.”

They note that “institutions seem to be successful in functioning as a political pressure valve for affective conflicts between various groups in society” and that consensus-based institutions “seem more capable of regulating or preventing the rise of hostile political or social camps…”

“In every country, there is inevitably disagreement about the substance of political decisions, but this does not always have to lead to hostile attitudes between the groups. In some countries with certain institutional designs, disagreement on the issues does lead to identity-based polarization, but in others it does not…

“Inclusive institutions might thus play a particularly important role in this “age of anger.”

The Way we Were: How Histories of Co-Governance Alleviate Partisan Hostility.

Horne, W., Adams, J., & Gidron, N. (2023). The Way we Were: How Histories of Co-Governance Alleviate Partisan Hostility. Comparative Political Studies, 56(3), 299-325.

This research looked at 19 western democracies between 1996-2017 and concluded that cooperative governance produced by proportional representation reduces partisan hostility and polarization among the public.

They analyzed “thermometer ratings” (feelings) of 76,187 respondents towards distinct political parties. They found that people felt warmer towards any parties that had been in a coalition government with their preferred party anytime over the previous 15 years.

This warmer feeling remained even if the parties that had been in a coalition together were ideologically far apart.

Arend Lijphart’s (2012) groundbreaking work comparing 36 countries over decades concluded that countries with proportional representation not only outperformed countries with winner-take-all systems on measures of democracy, they were “kinder, gentler” democracies.

Horne, Adams and Gidron help explain why:

“Proportional representation creates party systems with rich coalition histories, which in turn prompt the warmer cross-party evaluations we observe in more proportional systems.”

Keeping Your Enemies Close: Electoral Rules and Partisan Polarization.

Rodden, J. (2021). Keeping Your Enemies Close: Electoral Rules and Partisan Polarization. In F. Rosenbluth & M. Weir (Eds.), Who Gets What?: The New Politics of Insecurity (SSRC Anxieties of Democracy, pp. 129-160). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodden found that voters in countries with winner-take-all voting systems perceive their country’s political parties to be further not only from one another, but also from themselves as voters. In other words, winner-take-all systems are more polarized.

Rodden concludes:

“Proportional representation brings a powerful advantage: it can allow the political system to absorb the rise of new issue dimensions, from environmentalism to women’s rights to nativism, without the issue-bundling that facilitates all-encompassing American-style polarization.”

Civility and Hostility in Parliamentary Politics.

Kuniaki Nemoto and Pedro Franco de Campos Pinto (2019). Civility and Hostility in Parliamentary Politics.

Nemoto and Pinto (2019) studied the nature of political discourse in the New Zealand Parliament before and after PR was adopted in 1996. They found that partisan hostility decreased inside Parliament with proportional representation.

Analyzing 821,442 parliamentary speeches by MPs from 1987 to 2016, they found a marked decrease in anger and hostility in MP’s speeches overall after 1996, most significantly in the tone of ruling party MPs towards smaller parties who might one day be coalition partners with them.

Citizen leadership needed to deliver proven solutions

Citizen leadership needed to deliver proven solutions

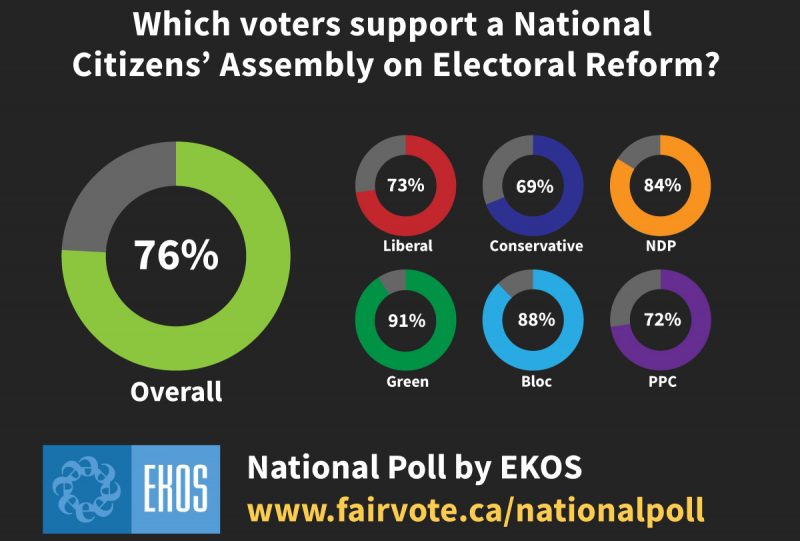

In the coming months Parliament will be voting on Motion M-86 for a National Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform.

This is an historic moment. In Canada’s history, Parliamentarians have never before had an opportunity to vote on a proposal like this.

When politics is getting in the way of progress, putting a non-partisan, independent Citizens’ Assembly in charge of finding solutions just makes sense.

It’s a bold, innovative and evidence-based proposal – and a hopeful step forward to deliver the kind of democratic renewal that Canada needs.