Five out of the last seven governments in Canada have been minority governments.

How to make minorities work

The way Canadians vote is producing one minority government after another. But many politicians have a hard time hearing the message.

For those whose worlds have long been consumed by the perspectives from their party war rooms, that’s understandable.

One party seizing all the power―with less than half the vote―has been the norm and the holy grail of our political system in Canada.

After all, since World War II, most governments have been “majorities”, but only four of those were actually won with a majority of the popular vote.

The lure of unbridled power that our first-past-the-post system can deliver has been driving the behaviour of our two major parties for 150 years.

It was the only reason we were forced into a snap election―a mere one year and eleven months after the last one.

It’s the fundamental reason that parties can’t seem to cooperate in Parliament, even when they have a lot in common.

Even when compromises are within reach.

And even when Canadians clearly want them to.

But in recent years, something is finally changing.

Simply put: It’s harder than it used to be to seize all the power with a minority of the vote.

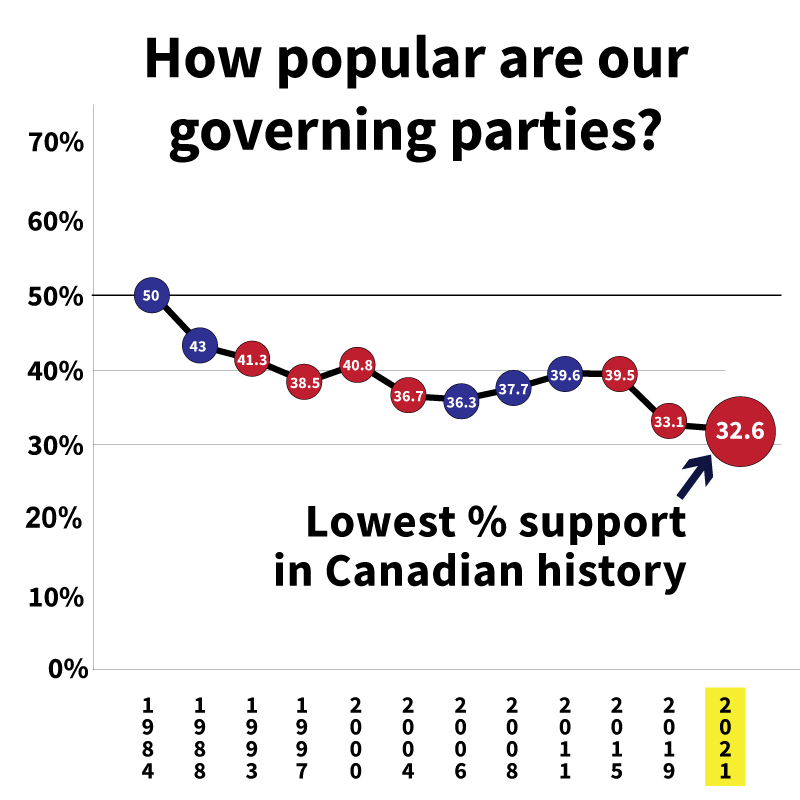

That’s because popular support for our traditional big two parties is on the decline.

This is not unique to Canada. Around the modern democratic world, citizens have been drifting slowly away from the big tent parties for decades.

They’re expressing their hopes, frustrations and values at the ballot through a range of new or smaller parties, including those on the centre, the left and the right.

But Canadian politicians and their party machines seem among the least prepared to deal with this profound shift.

Canada hasn’t been a two party system since 1921.

But because of our non-proportional first-past-the-post system, the biggest parties could count on massive seat bonuses and distortions to deliver them phony majorities anyway.

The system reliably suppressed the diverse opinions of Canadians and ensured that any cooperation with other parties was only a temporary inconvenience to those at the top.

But today?

It’s hard to transform 32.6% of the vote into a majority, even with first-past-the-post.

Listening to the Liberal Party’s former strategist Gerald Butts crowing on Twitter, we hear that for the political class, the solution to this problem lies in even more sophisticated ways of micro-targeting the electorate.

The political establishment is using data analysis and social media to target the few voters that matter with laser precision―and increasingly ignoring the rest. Maximum manipulation of the few―instead of attempts to inspire the many.

For the Liberal “victory”, Butts praises the “unsung team of super geniuses put together and led by @tompitfield at Data Sciences” for delivering the Liberals so many seats with so little popular support.

Do most Canadians share his enthusiasm for this approach to “winning” elections? Probably not, but we don’t matter anyway. That’s the whole point.

The big parties don’t want minority governments. They’ll pursue the elusive “majority” ruthlessly, down any legal path available.

Our politicians are not only responding to the incentives of the first-past-the-post system, some of them have become addicted to them.

How to make minorities governments work―for real

With minority governments becoming more frequent, pundits, columnists and political scientists are bursting with good advice for making minorities work.

The excellent column by Andrew Perez in the Observer is just one example. Perez stresses the need to:

“work collaboratively”

“focus on working across party lines”

“cease the permanent political campaign”

Entire shelves could be filled with books written on how to make Parliament work better.

Even Pauls Wells, among the most cynical advisors, offers “modest” suggestions to temper the relentless drive to campaign instead of govern, such as restoring the per-vote subsidy.

The problem with all these suggestions is the one lamented by Wells:

There’s “zero” chance of any of these solutions being implemented.

The only option left is to change the rules of the game

More recommendations for band-aid fixes just aren’t getting us anywhere. Watching Parliament year after year, anyone can see that.

If we want our parties to start acting differently―both on the campaign trail and more importantly, in the Parliament―then we need to change the rules of the game.

We can’t expect them to play a cooperative game on a chess board.

This is what the fight for electoral reform is all about. The rules of the game matter. Everything else flows from that.

A few examples of how the game shapes the culture and the outcome:

- 29 OECD countries with minorities and coalition governments continued governing during the pandemic. No snap elections. Because all had proportional representation. One party being up or down 4% in the polls doesn’t tempt anyone to trigger an election. When no single party can grab all the power, cooperation is expected and cooperation becomes the default.

- In June 2020 in Denmark, at the height of the pandemic, in a minority government, nine parties worked together to pass the toughest climate legislation in the world. Denmark has had proportional representation for 100 years, and all governments are cooperative. Years of practice pay off.

- In the summer of 2020 in New Zealand, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, head of a coalition government, decided to delay the scheduled election on account of COVID. This followed one of the world’s most effective responses to COVID 19 and her skyrocketing poll numbers. When Ardern went on to win an outright majority in the election, she reached across the aisle to ask Greens to be Ministers anyway, because she recognizes that serious collaboration on long term issues delivers better results.

- Ireland’s 2020 election helped usher in a new kind of politics. The previous government had been a minority. As in Canada, the two major parties have been on the decline for years. After the 2020 election, with about 25% of the vote each (and about 25% of the seats each), the two major parties decided to work together in a coalition, including the Green Party. They agreed to switch which one occupies the role of Taoiseach (Prime Minister) after two years. The three party coalition has crafted a five year plan including ambitious climate targets.

- During 2015-2016, Europe was experiencing a migrant crisis. Germany was led by a grand coalition government of Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP). The German Minister for Immigration, Refugees, and Integration at the time was also a Social Democrat. Together, they developed a plan that would see Germany take in half of the 2.6 million refugees who entered Europe. Merkel’s consensus-building approach has been praised around the world, and in the 2021 election, immigration was barely an issue.

First-past-the-post passed its best before date quite some time ago. Canada’s parties have been slow to respond, hoping for a return of the “good old days” when the first-past-the-post goose laid the golden egg more reliably.

Faced with an increasingly diverse electorate, which craves the kind of cooperation that delivers both stability and results, an opportunity to put the public interest first is at hand.

Only proportional representation can transform the culture in Ottawa.

80% of Canadians support a National Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform.

It’s time for politicians to get out of the way, and let citizens lead.