“He said he should have immediately shut down talk about proportional representation…” and “confessed Liberals were deliberately vague in order to appeal to Fair Vote Canada advocates.”

– Toronto Star article about the Justin Trudeau interview, October 3, 2024.

On October 1, 2024, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau repeated that one of his greatest regrets was not using his 2015 majority government (obtained with 39.5% of the vote) to just force through the voting system he wanted―a winner-take-all ranked ballot system properly called Alternative Vote.

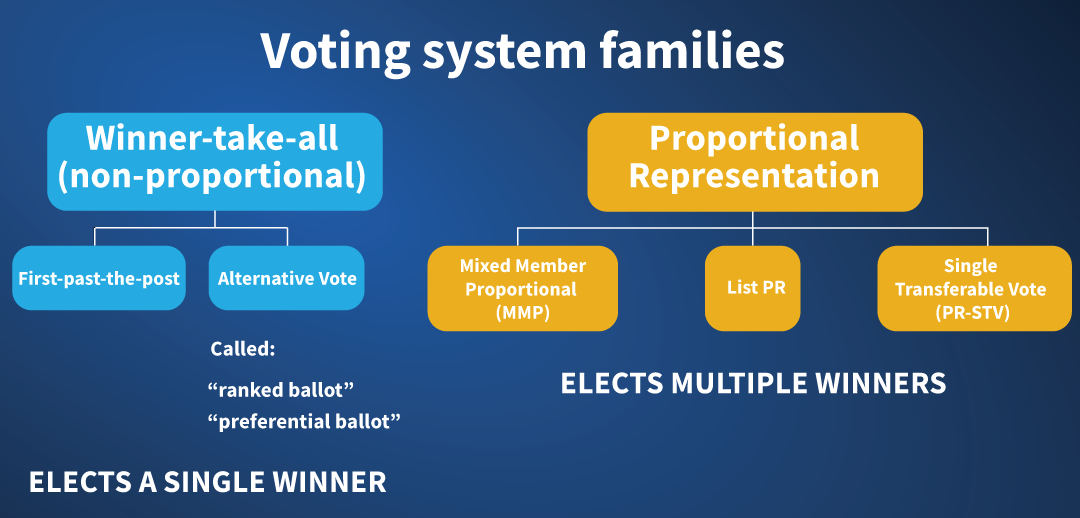

Alternative Vote replicates the problems of first-past-the-post. In some elections, it can produce even more disproportional results.

In the only OECD country where it is used at a national level, Australia, it has helped to entrench a two-party system for almost 100 years.

Byron Weber Becker, an electoral systems expert tasked by the federal Electoral Reform Committee with modelling election results for numerous systems under different conditions, demonstrated what other researchers had previously concluded: not only is Alternative Vote more disproportional than first-past-the-post, the most pronounced effect would be to deliver more seats to the Liberal Party.

An overwhelming majority of Canadians―fully 87% in a 2022 EKOS poll―rightfully reject the idea that any single party should be able to change the voting system to one preferred only by their party.

Almost every country in the OECD that has reformed their electoral system has done it through multi-party agreement.

In 2016, the NDP and Greens went out of their way to offer compromise solutions, including proportional systems that included a ranked ballot, and incremental approaches that would have added a very small element of proportionality to Canada’s electoral system. These attempts to negotiate were ignored.

In 2024, all the Bloc, Greens, NDP, and Independent MPs, 3 Conservatives and 39 Liberal Party MPs voted for a motion by NDP MP Lisa Marie Barron for a non-partisan National Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform, which would have fairly considered all options.

Despite 76% of the Canadians in support, this attempt to find common ground was rebuffed by the Prime Minister, too.

Fact Checking Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

Justin Trudeau’s talking points in the interview included several misleading statements that require correction.

1) Trudeau implied that his preferred system, Alternative Vote, is not a winner-take-all system like first-past the post.

The Prime Minister said:

“I look at where the world is going, and where polarization is happening, and where excesses of populism have been able to come in. And the winner-take-all version of first-past-the-post we have right now…” (He goes on to describe his view of first-past-the-post and advocate Alternative Vote).

There is no debate, it’s cut and dried: Alternative Vote is another winner-take-all system.

Political scientists usually bundle first-past-the-post and Alternative Vote together, in a family of winner-take-all systems they call “Plurality/Majority”.

With either first-past-the-post or Alternative Vote, there is one winner in each single member district. Other voters do not get representation.

Whether one winner “takes it all” or several winners are elected to represent the diverse viewpoints of the voters is what differentiates the winner-take-all family of systems from proportional representation systems.

2) Trudeau suggests that adopting Alternative Vote could help mitigate polarization.

The Prime Minister said:

“I look at where the world is going, and where polarization is happening, and where excesses of populism have been able to come in. And the winner-take-all version of first-past-the-post we have right now…” (He goes on to describe his view of first-past-the-post and advocate Alternative Vote).

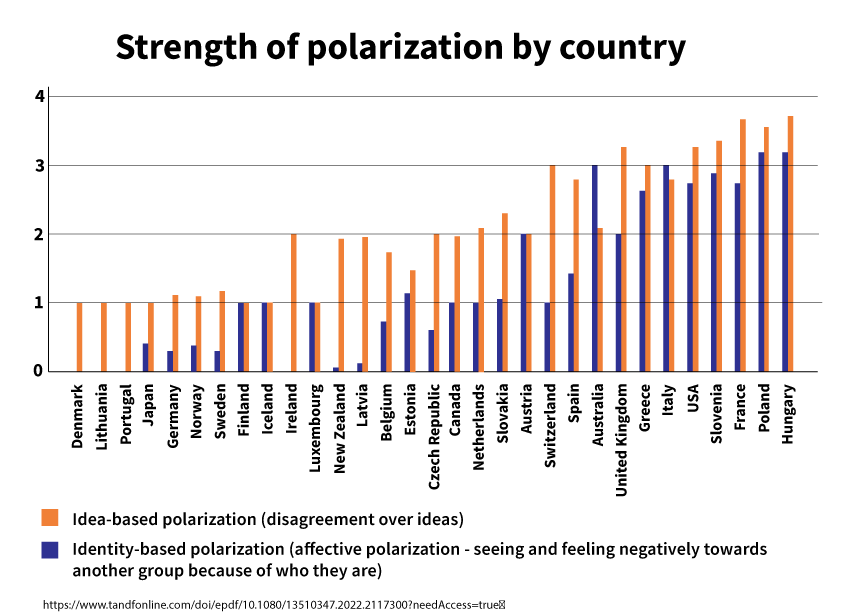

Research looking at 36 democracies from 2000-2019 shows that countries that use proportional representation have lower levels of polarization than those that use winner-take-all systems.

The only OECD country that uses Alternative Vote nationally is Australia, and identity-based (affective) polarization is far worse in Australia with AV than it is in Canada:

As John and Hargreaves (2011) note:

“Alternative Vote supports and perhaps encourages hostility between the largest parties thus contributing to Australia‘s harsh political culture.”

“Alternative Vote is also unique in its tendency to direct votes into seats for the two established major parties and prevent the success of new movements and parties, especially moderate parties”.

“Alternative Vote is found to be unique amongst ordinal methods in supporting a rigid, adversarial, two-party system.”

3) Trudeau claims that proportional representation makes MPs accountable only to parties instead of local voters and communities.

The Prime Minister said:

“The big one is I am really worried about decoupling members of parliament in the house from communities that they have to serve.

Then you also have people who got elected because they were on a party list and you have MPs who owe their existence as MPs to a political party as opposed to specific Canadians.”

These statements were so obviously untrue that Liberal MP Nathaniel Erskine-Smith attempted to interject twice to rebut them, saying:

“I don’t think any advocate in Canada is arguing for… doing away with local representation” and

“You can do open lists”.

The Prime Minister talked right over him.

All credible models of proportional representation for Canada are designed to maintain strong local representation. Local representation has been a core value of every commission and assembly in Canada that recommended PR.

All models of proportional representation for Canada mean MPs are directly elected, as individuals, by local voters to represent voters in a specific geographic area.

It is not believable that the Prime Minister made these statements because he does not know the very basics of how proportional representation for Canada could work.

The only reason he would have used misleading or discredited opponent talking points is to manufacture a contrast between his straw man PR system and his preferred winner-take-all ranked ballot system, to get around the problem he acknowledged earlier, namely that nobody agrees with him.

The entire segment makes the case for why electoral reform needs to be informed by evidence and decided by multi-party agreement, so one party (or leader) alone cannot control the agenda.

Leaving a Legacy?

Seven years after Justin Trudeau dismissed the expert consensus for proportional representation and declared “it was my choice to make”, the real fallout from the broken promise may soon be hitting Canadians hard in the face.

One of the consequences of all winner-take-all systems is policy lurch, where one government elected with a false majority undoes the work of the previous one.

Anand Menon, Professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs at King’s College London recently explained how it works at an event about polarization called “The Centre Cannot Hold”:

“If you think about the kinds of policy issues confronting us today, whether it’s climate change, aging populations, AI, maybe the thing they all have in common is they require medium to long term solutions. In multi-party systems you tend to get longer term public policies because parties are forced to compromise and work together.

If you look at the UK system, one of the greatest problems which I think is at least partly attributable to polarization is their complete inability to do anything even medium term let alone long term. A party comes in and what’s the first thing it does? It promises to overturn what the last party did.

We’ve reached that stage where a political party that thinks it’s going to win an election says we’d like to do this on a cross-party basis knowing full well that when push comes to shove our system just seems incapable of building those sorts of long term coalitions.”

If Justin Trudeau truly wants to foster politics that looks for common ground and to protect his legacy items such as Canada’s climate plan, he needs to get past his partisan myopia, take a good look at the evidence for electoral reform, and most crucially, be willing to compromise.