Voters in BC and the United States have something in common this week: both are on a knife’s edge, at the mercy of a winner-take-all system which has polarized the electorate. Key provincial policies like climate action and Indigenous reconciliation are at risk of abrupt reversal.

A mere 12 vote margin separates the BC Conservatives from the BC NDP in Surrey Guildford, where a judicial recount will decide if the BC NDP will be handed all the power in BC with less than half the popular vote.

The election has left the province deeply divided, with no incentive for parties to work together to solve problems that desperately require collaboration in the public interest.

How can BC voters ever expect to resolve long-term problems such as health care, the opioid crisis, and affordable housing when their carefully-laid plans can be flushed down the toilet every four years over a margin of 12 votes?

Divided by the cutthroat politics of first-past-the-post

First-past-the-post has left BC more divided than ever.

John Rustad and Kevin Falcon’s gambit to force voters into the straightjacket of a two-party system, where votes for one party are motivated by fear and hatred of the other, was largely successful.

Not only were voters deprived of choice and pitted against one another, the skewed results have exacerbated regional tensions.

First-past-the-post has painted a swath of blue across almost all the seats in the Interior and the North, a strong contrast with the bright orange in much of the lower mainland and southern Vancouver Island. One could be forgiving for assuming that voters in different regions have nothing in common.

But looks are deceiving. The urban/rural divide was sharply exaggerated by the voting system. For example, the Conservatives won only fifty-one percent of the vote in BC’s interior and North―but first-past-the-post gave them 84% of the seats (21 out of 25 seats). Independent MLAs finished second to the Conservatives in two ridings and captured six percent of the vote across those regions.

The reverse also happened in NDP-dominated areas. The wall of solid orange on southern Vancouver Island masks the fact that both major parties had almost equal support in several ridings.

Clearly, many voters wanted more centrist voices in the legislature but were denied representation.

Parties must seize the chance to introduce proportional representation

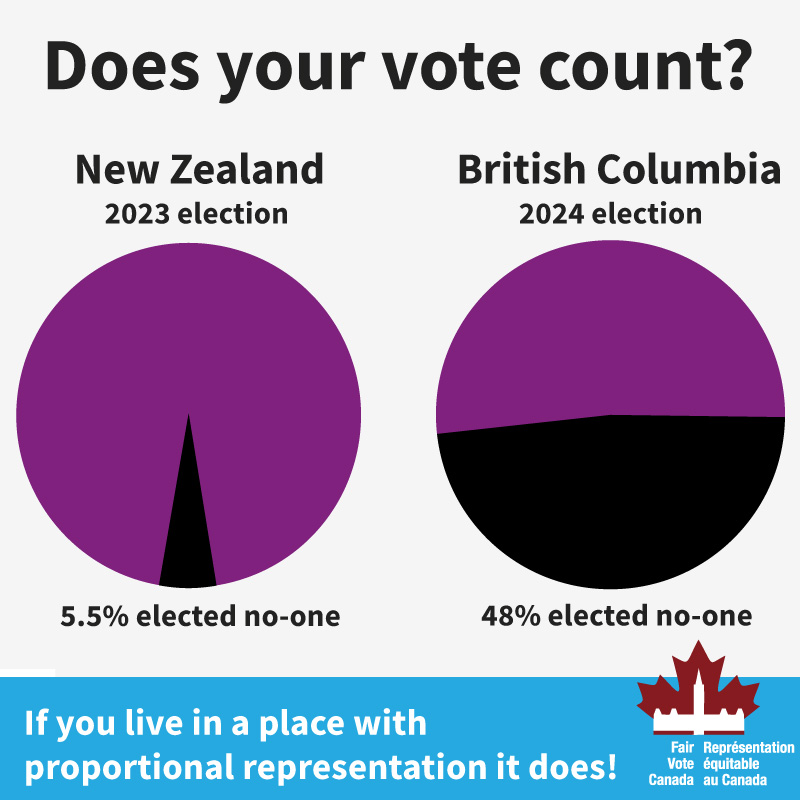

Seeing their government determined by a few votes in one or two ridings after multiple recounts is causing many British Columbians to rethink the fairness of their voting system. BC voters have strongly supported proportional representation in polling for decades. Despite a solid, evidence-based recommendation from a world-class citizens’ assembly in 2004, politicians in BC’s biggest parties have a long history of sabotaging proportional representation for the sake of their own self-interest.

If the supposed advantages of our winner-take-all system are its ability to cater to the centrist voter, ensure “strong, stable majority governments”, prevent “backroom deals”, deliver fast results on election night, and keep out extremists, it has failed utterly on all counts―all at once.

The results of this election―whatever they finally turn out to be―have exposed such arguments for what they have always been: a thin cloak to cover pure partisan self-interest.

Multi-party agreement for electoral reform is the path to progress

One of the most common questions people ask is, “How did other countries get proportional representation?”

While the political opportunity that opens the door to PR is unique in each jurisdiction, the “how” boils down to one thing: multi-party agreement.

The strongest democracies in the world got proportional representation precisely this way.

This does not mean every party agreed in every case. Parties who gain the most from a first-past-the-post system at any given moment―or even imagine themselves reaping the rewards in future―may sabotage negotiations, and put up a vicious fight to keep the status quo.

While the road to reform can be rocky and halting, parties in other countries have succeeded in negotiating, compromising and hammering out an agreement for a proportional system.

Far from locking in a government of any particular stripe, as opponents would have us believe, proportional representation simply levels the playing field by ensuring that parties receive seats that reflect their actual support. A party winning 40% of the vote would win 40% of seats.

In jurisdictions around the world, proportional representation has given voters across the political spectrum fair representation and given parties in the left, centre and right opportunities to lead the government, while incentivizing cooperation and delivering better results for citizens.

Regardless of whether we have a minority or a majority government, it’s clear that BC’s voting system needs urgent reform.

Parties that care about a fair and inclusive democracy, are serious about finding lasting solutions to the challenges facing BC, and are committed to putting people ahead of power will know that proportional representation is the first thing to do.