You may have noticed that some academics will answer a question about Canada switching to proportional representation by saying something like this:

“There’s no perfect system. Electoral reform is all about trade-offs”.

Before accepting the latter part of this claim uncritically, it’s worth asking:

What is a “trade-off”?

How well does the framing about trade-offs work to convey what’s really at stake in the debate over proportional representation in Canada?

A quick google search turns up the following definition of trade-off:

Along similar lines, the Helpful Professor says:

“A trade-off refers to a situation in which gaining one benefit requires sacrificing another.”

The key here is that a trade-off means you must choose between “incompatible” things. You may gain something, but that means sacrificing something else of value in the process.

At first glance, it sounds logical, because we make these kinds of choices all the time.

A few examples of choices that might be considered trade-offs:

You can split the cost of your apartment with a roommate or live alone, but you can’t do both.

You can spend the family’s holiday budget on a short cruise or a long road trip, but you can’t afford both.

If you live in Ottawa, you can move closer to your grown children in Toronto or your aging parents in Montreal, but you can’t move closer to both of them.

In every case, in order to get something, you’re giving up something else―and enduring some negative consequence as a result. It’s a trade-off.

But is this actually the right language to frame the choice between keeping first-past-the-post or adopting proportional representation in Canada?

When academics suggest that adopting proportional representation involves trade-offs, it’s worth looking closely at the evidence, to the point of asking which of the trade-offs are substantial, or even real.

The public can spot phony trade-offs

Whether the trade-offs are accepted uncritically or not depends on the context and the messenger.

In 2016, the federal all-party committee on electoral reform (ERRE) completed a five month long study on electoral reform options for Canada. They heard from hundreds of experts from Canada and around the world. They toured the country listening to Canadians.

At the end of it, 88% of the experts and public participants were in favour of proportional representation.

It wasn’t the outcome Justin Trudeau wanted to hear.

The Minister of Democratic Institutions then sent out a survey to every Canadian household featuring 17 “even if” questions.

“Even if” is obviously a way to present a trade-off as if it were a fact.

To give you an idea of the flavour of the “even if” statements people were tasked with ranking from strongly agree to strongly disagree, examples included:

“There should be parties in Parliament that represent the views of all Canadians, even if some are radical or extreme.”

“A ballot should be easy to understand, even if it means voters have fewer options to express their preferences.”

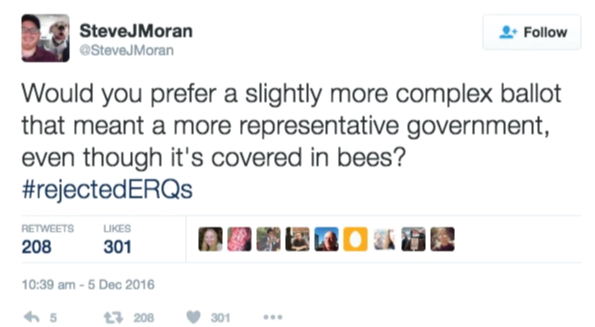

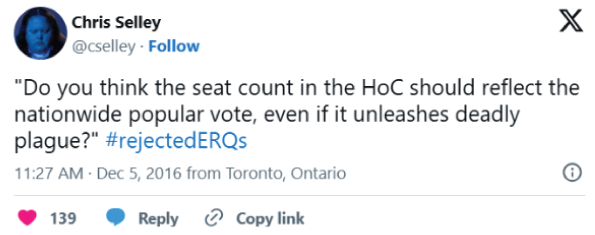

Almost overnight, Twitter exploded with over 20,000 people mocking the survey questions for their phony trade-offs:

The motives of the Liberal Party in framing the choices were so obvious that the public was easily able to discern that the trade-offs were ridiculous, exaggerated or lacking a realistic counterbalance with the realities of first-past-the-post.

Yet these questions had been reviewed and approved by an academic panel.

When these same trade-offs are presented to us directly by an academic (rather than through a Liberal Party survey, for example) we are much more likely to trust them as fact.

However, even when a trade-off is being suggested by someone with no motive or intent to mislead us, it still warrants a closer look.

Who can we trust?

Trusting experts in general is a good thing. When academics generalize about trade-offs of electoral reform, they’re not trying to undermine progress towards proportional representation in Canada.

As Professor Dennis Pilon, one of Canada’s top experts in electoral reform, says:

“Academics try to assume a neutral role in a divisive debate, offering an assessment of ‘both sides’ in any given dispute. This has produced a dominant “trade-offs” discourse, in response to reformers and as an academic being neutral by default.

While the tendency to frame the debate in terms of trade-offs may be understandable, is it defensible?

Do the characteristics of the ‘trade-offs’ make sense? Does the empirical evidence support the claims that trade-offs do in fact exist, and if so, can we measure the relative weight or impact of each side?”

Voting systems and electoral reform is a special area of expertise

Electoral systems and electoral reform―the design of systems, the political history of their adoption, their real-world consequences, and exactly what is proposed for Canada―is a special area of expertise in political science.

Just like a family physician isn’t an expert in the diagnosis and treatment of certain complex conditions, political scientists have specialties and are not all equally familiar with electoral systems and electoral reform.

When an academic generalizes about trade-offs, it can sound like they are saying “since there are pluses and minuses to every system, one option is probably no better than any other”.

Yet when we look closely at the options for proportional representation actually recommended for Canada and the experience of countries that use these systems, many of the so-called trade-offs may not even exist.

Lived experience matters

Imagine you are participating in a class about electoral reform for Canada. You are being told that types of proportional systems come with certain trade-offs. Before accepting the validity of this claim, wouldn’t you want to learn from experts who live in countries with the types of proportional systems you’re exploring?

Before accepting the validity of this claim, wouldn’t you want to learn from experts who live in countries with the types of proportional systems you’re exploring?

Such experts are not hard to find.

Equally important, wouldn’t you want to talk to regular citizens who live in countries with the kinds of proportional representation you’re considering, to see how they experience things like voting and local representation, compared to your experience in Canada with first-past-the-post?

Such citizens are not hard to find either.

Conversations with people who have lived experience can test academic assumptions about trade-offs and influence your point of view.

When misleading information about trade-offs goes unchallenged

We all know that misinformation that is repeated over and over is more likely to be accepted as fact.

For 14 years Justin Trudeau has been claiming that if Canada adopts proportional representation, MPs won’t be elected by voters to represent “real communities” or “actual communities”.

In other words, you’ll lose your local representation.

That would certainly be a real trade-off―if it were true.  Justin Trudeau obviously knows that the proportional systems recommended for Canada for the past 100 years all maintain strong local representation.

Justin Trudeau obviously knows that the proportional systems recommended for Canada for the past 100 years all maintain strong local representation.

Every committee or commission in Canada that has recommended proportional representation has prioritized local representation as a top value.

In fact, proportional representation systems for Canada could strengthen local representation by ensuring that voters in every region will have MPs from the governing party and in the opposition fighting for their communities.

When it comes to proportional representation models for Canada and local representation, there’s no trade-off.

That’s why, when Trudeau repeated his malarkey about PR and local representation in his 2024 interview with MP Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, Nathaniel jumped in to interrupt him and attempted to correct the falsehood.

Trudeau instantly deflected to change the channel, but not before hundreds of thousands of people watching were again exposed to a claim about a phony trade-off about proportional representation.

Bottom line: “Electoral reform is about trade-offs” is a common framing in the debate about electoral reform. It may not be the most appropriate place to start, and Canadians should be wary of accepting claims about specific trade-offs without a closer look at the evidence.