white

Women and Proportional Representation

While women’s participation in politics can only be explained with reference to a wide range of variables, the research community is united in declaring that PR elects more women. One of the most widely accepted theories is that multi-member districts allow more women to be elected because parties will want to put forward a diversified slate of candidates to reach a wider range of voters.

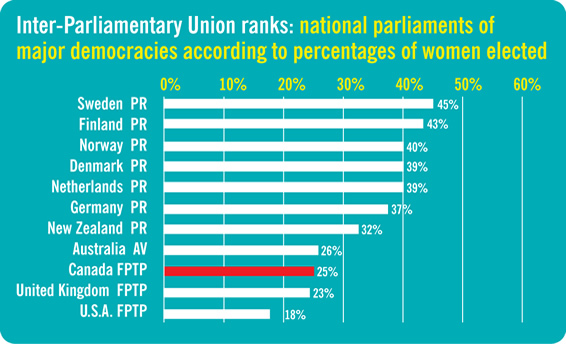

Canada, the US, the UK, France and Australia’s lower house all vote with majoritarian electoral systems and all share an embarrassingly low rate of women in their legislatures. None reach or exceed the most basic target set by the United Nations of 30% representation of women in politics. In comparison, legislatures in PR countries such as New Zealand, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark all include over 30% women. Sweden tops the chart at 45%.

In Canada, more women are running for office. There were 533 women candidates in the 2015 federal election. However, only 16.5% of those women were elected. Women’s representation in Canada’s House of Commons has been increasing very slowly in Canada, and by 2018 was still only 27%.

M – white

Menocracy, abridged in this short video, is a documentary about the barriers facing women in Canadian politics.

Gretchen Kelbaugh, who produced the Menocracy documentary, is a screenwriter, author, journalist and filmmaker. Her biography “With All Her Might; the Life of Gertrude Harding, Militant Suffragette” is published in three countries. Her book of nonsense rhymes for children, “Lollipopsicles,” won several awards. Gretchen twice won the Atlantic Film Festival’s CBC Script Development competition. One her films, “106 Fire Hydrants,” was produced for national CBC-TV in 1999. Since then, Gretchen has independently produced and directed documentaries and drama which have been screened around the world, winning several awards for books and videos. She works from her home along the Kennebecasis River in New Brunswick.

Gretchen Kelbaugh, who produced the Menocracy documentary, is a screenwriter, author, journalist and filmmaker. Her biography “With All Her Might; the Life of Gertrude Harding, Militant Suffragette” is published in three countries. Her book of nonsense rhymes for children, “Lollipopsicles,” won several awards. Gretchen twice won the Atlantic Film Festival’s CBC Script Development competition. One her films, “106 Fire Hydrants,” was produced for national CBC-TV in 1999. Since then, Gretchen has independently produced and directed documentaries and drama which have been screened around the world, winning several awards for books and videos. She works from her home along the Kennebecasis River in New Brunswick.

In her words

As a dual citizen, I grew up proud in the knowledge that both Canada and the USA are beacons of democracy. After all, our governments have their roots in the UK. A democracy should represent the views of its citizens; how do our governments measure up with others in how they represent women?

The Inter-Parliamentary Union ranks national parliaments of major democracies according to percentages of women elected. Here are some rankings of Women in Government in a 2015 sample of PR and majoritarian OECD Countries (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development):

On a worldwide level, this pattern is repeated: of the five countries in the world who have 30% or more female parliamentarians in their single or lower house (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands), three have a proportional electoral system, and two have a mixed proportional electoral system. None have a majoritarian system. Of the eight countries that have 29-25% female MPs in their lower or single house (New Zealand, Seychelles, Austria, Germany, Iceland, Argentina, Mozambique and South Africa), all have either proportional or mixed proportional electoral systems. Again, none have a majoritarian system. In contrast, if one looks at the lowest worldwide level of female political representation, a far higher proportion of countries with 10% or less women in the lower or single house of Parliament have a majoritarian electoral system, and nearly 90% of countries that have no female parliamentarians using a majoritarian system.

Dr Joanna Everitt, Dean of Arts at the University of New Brunswick in Saint John and a Professor of Political Science specializing in women and politics, is now a visiting fellow in the Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard University. She says that if Canada were to switch to a Proportional Representation voting system (PR), then in the very next election our percentage of women MPs would jump by at least 10%.

But why does it really matter if we elect more women to government?

First, attitudes differ by gender. Separate studies in Canada, the UK and the USA show that female politicians (as with women in general) tend to care more than their male colleagues about social welfare issues such as health, education and poverty. Conversely, male politicians tend to care more about economics, the military and foreign affairs. Put both genders together, and we have it all covered. Of course there are many examples of women and men who don’t fall into these generalities. The sexes have more in common than not. Still, small differences of 5 % – 15% in attitudes of MPs can cause big differences in government legislation and policy.1

The second reason why we need more women to help make the laws that rule society is that their experiences differ from men’s. Women still do the most childcare and eldercare; they do more than half of the housework (a time commitment); they experience the workplace differently (require more leaves, experience more harassment, have not broken the glass ceiling); they make less money; and they are far more apt to be the victims of family and sexual violence. We need the perspectives of women to develop legislation and policies that deal more fairly with these areas of life. In fact, almost all areas affect women differently, from taxation and pay equity to divorce law.

Third, women and men tend to use different leadership styles. Even today, we equate strong leadership qualities with typical male behaviour. Rt Hon Kim Campbell points out in Menocracy that men tend to challenge, take strong positions and favour a hierarchy of power. Women, who have been taught all their lives to cooperate and negotiate, tend to like power-sharing and consensus-building styles of leadership, now embraced by the IT sector. Neither one is better, but having a mixture of leadership styles makes for better government.

Finally, because women leaders tend to negotiate longer than men when it comes to military decisions, the world stage will change when half our leaders are women. Kim Campbell puts it well: “Girls are not socialized to have certain kinds of bravado and physical courage, etc, defining them as members of their sex in the way that boys are. So I think the value that women bring is that they don’t have the same ego needs to be seen as tough in that way…. There’s no ‘gonad-al’ fortitude required to be shown, and I think for that reason women are much more comfortable looking at all of the options and trying to see through the rhetoric and the excitement that comes from the possibility of violence.” For many crucial reasons society needs equal numbers of women and men making the rules and policies that so affect us.

How does PR voting create governments that better reflect society, not only with more women, but with more minorities? It’s simple. PR provides natural incentives for parties to give voters more choice. This means each major party will give voters the choice of more than one candidate on their ballot. As soon as they present more than one candidate, the incentives offering the public balance and diversity start to operate.

Substantial research has been conducted comparing outcomes in countries using winner-take-all systems vs proportional systems. Arend Lijphart (2012), a world-renowned political scientist, spent his career studying the differences between majoritarian and “consensual” (PR) democracies. In his landmark study – Patterns of Democracy – Lijphart compared 36 democracies over 29 years, and found that in countries using proportional systems elected women to parliament 8% more than majoritarian (fptp) systems. He has stated that “the representation of women in parliaments and cabinets is an important measure of the quality of democratic representation in their own right, and it can also serve as an indirect proxy of how well minorities are represented generally.”

Lijphart sums it up best when he says, “Political equality is a basic goal of democracy and the degree of political equality is therefore an important indicator of democratic quality.” At our current rate of growth it will be close to 100 years before Canada has equal numbers of women and men in parliament and legislatures. Let’s accelerate this by demanding we catch up to the rest of the democratic world and switch to a system of Proportional Representation to make ALL our votes count!

- Interviews with Dr Joanna Everitt, Dr Susan Carroll (CAWP, Rutgers, USA) and Dr Rosie Campbell (Birkbeck, UK) in Menocracy.