The occupation of Ottawa caused a fundamental shift in our Canadian self-identity. The look of smug superiority that sets in when we compare ourselves to our southern neighbours was wiped off our collective faces―for good.

We realized that we are not immune to the forces that are making that country nearly ungovernable―and that we are not that different.

While some cheered the protesters and applauded their commitment, others watched in stunned disbelief as the paralysis in our capital city drew admiration from US far-right media pundits such as Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson and sparked copycat actions across the globe.

The occupation may have been partially funded by US donors, but there’s no escaping that it was supported by millions of disaffected Canadians and fueled by the partisan sniping of our mainstream politicians.

We are not only vulnerable to a spillover from the democratic chaos and the angry, tribal divisions south of the border, we are cultivating our own—abetted by an electoral system that incentivizes partisanship above all else.

Two weeks into the convoy’s occupation, 27% of Canadians remained in support of the convoy’s approach and behaviour—hardly a “fringe”. The anti-government messages on display obviously resonated with a large segment of Canadians.

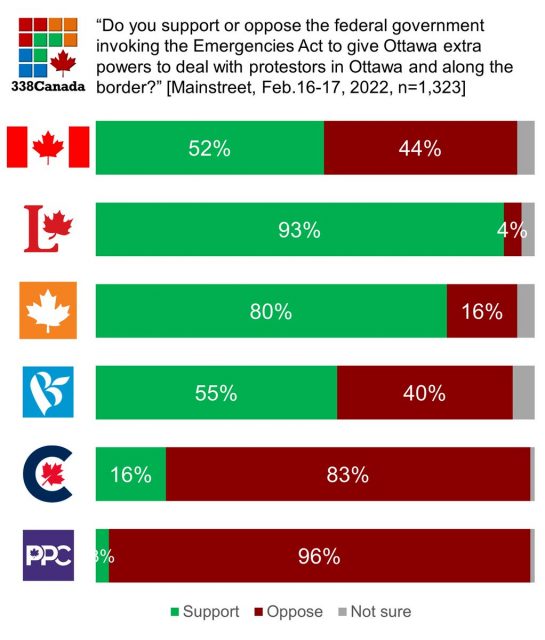

It was no surprise to see a split along party lines, but the degree of partisanship was striking.

An opinion poll on the use of the Emergencies Act revealed partisan divisions that rival the worst of what we see to the south: 93% of Liberal voters in favour vs 83% of Conservative voters opposed.

The questions that should be occupying the minds of every political leader in this country right now are:

What are we going to do about it? How do we fix this?

Academics and public opinion researchers have been warning of the growing and deepening political polarization in Canada for years.

They flagged a hardening of attitudes towards tinder-box topics such as immigration. Climate action. And yes, COVID protocols.

But their cautions have largely fallen on deaf ears.

Too many politicians on all sides prefer to keep energetically fanning the flames of division, doubling down on the winner-take-all mentality that got us into this mess.

Our most prominent political leaders continue to sell the fable that a victory for their party in the next election will solve the problem created by the “other”.

After all, wasn’t the issue of how to deal with COVID—and which values shall rule the nation in general—settled when Justin Trudeau “won” the election, with 32% of the vote?

Won’t these problems go away if the Conservatives can broaden their tent just enough to capture all the power with a whopping one third of voters—and make Canada great again?

A consensus is forming for proportional representation

More opinion leaders than ever before are asking:

How can a political system that is built for parties to win by dividing people be used to bring us together?

Short answer: it can’t.

Rather than encouraging dialogue and healing divisions, winner-take-all political systems fuel the anger of the many Canadians who feel excluded from their own Parliament.

Rather than facilitating a healthy discussion between dissenting views, they merely drive a bigger wedge between voters who have representation— those who are more likely to feel heard—and those who don’t.

Sean Speer, Assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and senior economic adviser to former Prime Minister Stephen Harper, gave a prescient warning on TVO’s The Agenda in 2021:

My primary concern is how do we make sure our political system is more representative and responsive of minority views. I think one of the mistakes that we’ve made is we’ve sought out an efficient political system at the expense of representativeness and responsiveness, and I worry that that creates the conditions for real political disruption down the road.

One of the things we need to grapple with is what institutional changes do we need to make, including proportional representation, to ensure our system is more representative and responsive, recognizing that will come with trade-offs but I think in the long run, that is the safer, more stable, and ultimately more democratic way to move forward.

As Star columnist Chantal Hébert said on the National on February 23, 2022:

If we had a Parliament that had proportional representation, and if some of those voices, as much as many will dislike them, were represented in the House, … it would be healthier to have them in the House than to have them on the outside.

Just days ago, David Herle, former federal and Ontario Liberal Party campaign manager and host of the Herle Burly podcast concluded:

I hate proportional representation. And I think this is pushing us inevitably towards proportional representation. You can’t give majority governments to people with 30% of the vote. It’s not legitimate.

As the NDP’s Democratic Reform Critic, Daniel Blaikie, explained just months before the convoy, speaking of the rise of the far right:

Our democratic system is about how we mediate conflicts.

We’re not going to beat people by trying to force them into silence. And part of the strength of their movement and part of why it’s gaining the momentum is the sense of not having a way to express themselves, of not being heard…

When there are real differences we need to find a way to mediate them in a peaceful way. Having a better democratic system gives more people the opportunity for their voice to find expression and then to deal with it in a way that is peaceful and where they’ve had some due process.

The best solution and the way we’re going to build stronger communities and a stronger country is by making sure we get the democracy part right first.

On June 22, 2021, all parties with MPs on the Procedure and House Affairs (PROC) committee except the Conservatives voted to study a National Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform.

It’s clear that Canada needs proportional representation.

To advance in this direction, politicians need to set their partisan interests aside and get out of the way. And they need to act quickly.

As EKOS pollster Frank Graves noted just two weeks ago:

I have been studying social cohesion and democracy for longer than I want to remember. At no point have I ever been so concerned about the basic resilience of our public institutions. We may have reached a breaking point.