By Yared Mehzenta

By Yared Mehzenta

Yared Mehzenta is a political observer and policy wonk originally from Western Canada but based in Toronto. Catch him dropping hot takes on Canadian political affairs, city things like transit and housing, and more. Go Jets Go.

Yes, Our Electoral System is Still Broken.

And no, the far-right shouldn’t scare us away from meaningful electoral reform.

Oh, did you hear? There was an election in Canada.

Yep, you may have missed it if you blinked but on September 20th Canadians went to the polls. The results are in and as it turns out, we got… more of the same.

The same Liberal minority government led by Justin Trudeau that we had before the election; the same constellation of opposition parties who all received more-or-less the same number of seats and votes as they did in 2019.

And yes, the same pre- and post-election chatter about how unfair and frustrating our electoral system is.

This has become routine of course. Every election, we are reminded that our First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) produces all kinds of distortions: it regularly turns a minority of votes into a majority of seats while awarding excessive representation to regional parties at the expense of smaller ones. Every election we have the obligatory hand-wringing about the merits of “strategic voting”, and every election we cast our ballots for local candidates whom often we neither know nor care much about (instead of voting for the party leader or just the party writ large), because that’s the way we’re asked to exercise our franchise. That’s just the way our system works, we are told. *Shrug.*

Except that all of that was supposed to change after 2015. You may recall that Justin Trudeau promised, repeatedly, that if elected he would ditch FPTP and replace it with a new voting system. He repeated the promise hundreds of times while in office too. Then that promise was very famously broken, and thus, here we sit, in 2021, with another FPTP election in the books.

The recent election results have made electoral reform, and particularly the concept of proportional representation (PR), a hot topic again in recent days- at least among the chattering classes – for a number of reasons that I want to discuss here. But first I need to do a quick bit of explaining, because I know that talk about different voting systems can get muddy.

First-Past-the-Post (where’s the post?)

First things first: how does our current system work? FPTP is actually quite simple. The country is divided into electoral districts, or “ridings” (338 of them in total), and each riding elects one MP. When you go to vote, you choose from the list of candidates running to be the MP in your local riding. The candidate with the most votes in the riding gets to be the MP. Usually, that candidate runs under a party banner. The party that gets the greatest number of its candidates elected as MPs typically gets to form government, and that party’s leader becomes the Prime Minister. That’s it, in short. There’s a lot of caveats but that’s basically how it works.

It’s a straightforward system, but in a multi-party environment with as many as six competitive parties, it can produce some pretty uneven outcomes. Consider that in any given riding, there is no threshold of support that a candidate has to achieve to get elected. All that matters is being the most popular candidate in a riding. In theory, this means that in a riding with many competitive candidates, someone might squeak into office with less than, say 30% of the votes cast. By contrast, an extremely popular candidate in another riding could win their seat with 70% of the votes or more. Both candidates get the same reward- a single seat. Meanwhile, all the votes for candidates who came in 2nd or worse amount to precisely nothing when it comes to the awarding of seats. Aside from the little sticker they hand out at some of the polling stations that says “I Voted”, unless you vote for the winning candidate in your riding, you gain absolutely nothing from the process. Nobody genuinely represents you in Parliament, nor did your vote help to get anybody elected. Sure, your vote is counted, but it doesn’t really count towards much of anything.

FPTP also fails to take into account the total proportion of votes that each party receives across the entire country. In truth, we don’t have one general election in Canada; we have 338 distinct elections in each riding, and they are, for all intents and purposes, independent of each other. This, of course, is not how the vast majority of Canadians think of our elections. Most voters cast their ballot based on either the broad-based values of their preferred party, the individual characteristics of the party leader, or the policy proposals in a party’s platform – or some combination thereof. Very, very few voters are motivated primarily by the personalities running in their local riding (only about 4% of voters, according to recent research on this topic). Most voters think that their vote is helping to achieve increased representation for their preferred party, and yet, the total support that each party receives across the country does not translate in any consistent way into parliamentary seats.

The Funhouse Distortions of 2021

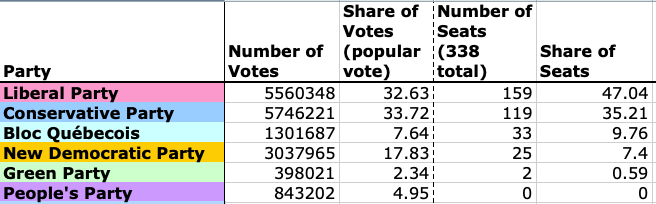

Consider the 2021 election results, which I’ve summarized in the chart below.

I want to hone in on three key distortions that can be observed in these results, one for each tier of party. In the top tier- the Liberals and the Conservatives- we see that the Liberals once again got fewer votes than the Conservatives (just as in 2019), but significantly more seats. I wrote previously about the Conservative Party’s problem with an inefficient vote distribution and, unfortunately for them, this proved true again. The Liberals routinely win more ridings than the Conservatives do with fewer votes, because a greater proportion of their wins are in ridings that are close contests. By contrast, the Conservatives win many seats by very large margins (particularly in the prairies) – margins that don’t actually help improve their seat count. If 30% of the votes is enough to win a seat in a riding, getting 70% of the votes doesn’t do much to improve your standings. At the end of the day, under FPTP, a seat is a seat. Regardless of whether you support the Liberal or Conservative parties or neither, there is a basic unfairness here: votes should count equally, regardless of where the voter happens to live. It shouldn’t be the case that your vote matters more because you happen to live in a swing riding, or that your vote is effectively meaningless because you live in a “safe” seat.

The second distortion here (which again, is almost a carbon copy of the 2019 election), is in the middle tier of parties – the NDP and the Bloc. The NDP received significantly more votes than the Bloc (almost 18% to the Bloc’s 7.6%) and yet the Bloc won a bunch more seats than the New Democrats, once again securing 3rd place status in the House of Commons and relegating the NDP to 4th. This is a textbook illustration of the regional distortion effect of FPTP: parties that cluster their votes regionally (as the Bloc Québecois does by only running candidates in one province) are disproportionately rewarded with seats, while parties that achieve a similar or higher vote share, but in a thinner dispersal across a wider geography, are punished by their inability to win ridings. The result is that our Parliaments are often much more regionally polarized than is truly the case based on actual vote distribution. And in this case, our next Parliament will continue to perpetuate the fiction that the Bloc is more popular than the NDP.

The third distortion that last week’s election produced, and perhaps the most significant one (surprisingly), is in the bottom tier of parties that were scratching and clawing to win any seats at all, namely the Green Party and the People’s Party. The Greens suffered an unfortunate (but not unexpected) fall from grace, collapsing to a mere 2.3% of the votes- less than half the share they received in the previous election, and significantly below the far-right PPC (at just under 5%). Yet the Greens managed to hold on enough to win two seats, while the surging PPC were shut out. In many ways, the rise of the PPC under Max Bernier and his demagogic appeals to anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists, is the most notable new development to emerge from the 2021 campaign. It remains to be seen whether the party will remain a force beyond one election cycle or turn out to be a pandemic-induced flash-in-the-pan.

And while many of us may hope for the latter, those of us who support electoral reform have had to reckon with the observation, noted by many a Twitter analyst, that the PPC were unable to break through in any of the 338 ridings under FPTP, winning zero seats, while under a system of pure proportional representation, they might have received as many as 17 seats (~5% of 338). Is this a damning indictment of the pitfalls of PR?

PR: A principle, not a system

At this point, it is necessary to spell out just what we mean when we talk about proportional representation.

Every electoral system that’s used to elect a large body of representatives (a Parliament, house of representatives, etc) necessarily involves trade-offs. The mechanism that determines how votes are translated into seats inherently prioritizes certain objectives over others. FPTP is a system that prioritizes, above all else, geographic locality of representation. By carving up the map into hundreds of (relatively) small geographic units, and then forcing voters to filter their voting preference through the lens of a local candidate race, FPTP ensures that precisely one representative is elected from each and every geographic constituency in the country. While that may be a noble objective, it is incumbent upon us at some point to ask: is that the most appropriate way to organize a federal election? How important is it to Canadians that their MP comes from their local community? Or, to put it another way: if you could only have one representative, would you rather it be somebody from your local community, even if they may represent a political party you hate, or would you rather have a representative who shares your values and policy objectives- though they may hail from further afield?

To ask the question is to answer it. Nobody wants to be represented by someone they dislike and for whom they did not vote. This is why other electoral systems, such as those used in many countries in Europe, prioritize a different objective: proportionality of party-based representation.

The idea is simple: the share of votes that a party gets should resemble, as best as possible, the share of seats that a party gets. If the Liberals got 33% the votes, they ought to be entitled to roughly 33% of the seats in Parliament – not much more and not much less. A proportional system encourages voters to vote for their genuine party preference, knowing that their vote will count towards the overall vote share for their preferred party, which is then used to determine the seat count.

Proportional systems also eliminate the need for so-called “strategic voting” (voting for candidate A even though you’d rather vote for candidate B, because you think candidate A has a better shot at beating candidate C, whom you detest, in your riding). PR eliminates false majority governments – where a party wins a majority of the seats, allowing them to govern with an iron fist, despite receiving a minority of the votes – and lowers the effective threshold for smaller parties to achieve meaningful representation. In countries that use PR, typically a somewhat greater number of parties is present in parliament than what we are used to in Canada, and parties are generally obliged to work together to form coalition governments, instead of the one-party rule that is commonplace here.

But it’s important to note that PR is not an electoral system in and of itself. Rather, it is a family of electoral systems that use different mechanisms to achieve the same basic principle – proportionality. The purest form of PR (which nobody seriously advocates for Canada) is the party list system. Each party drafts an ordered list of candidates (in Canada, it would be 338 names long). When you vote, you simply vote for your preferred party- no candidate selection necessary. The party votes are tallied, and each party is awarded a number of seats that matches their share of the popular vote. To use the previous example again: if the Liberal Party won 33% of the votes, they would be awarded 33% of the 338 seats in Parliament – 111 seats – and the first 111 names on their party list would become MPs. Under pure party list PR, there are no ridings or geographic districts built into the system. The onus is simply on the parties to determine for themselves how important it is for their list of candidates to reflect the country’s geography.

What I have described are two extremes on a spectrum of electoral systems. On the one hand, FPTP is extreme in its emphasis on localized representation, while setting aside entirely the question of whether the electorate’s relative support for the national parties is accurately represented. This produces quirky and unpredictable outcomes that often feel unfair to voters. On the other hand, pure-list PR is extreme in its emphasis on party representation, while ignoring the regional dimension of elections, which is particularly important in a large country like Canada. This can potentially lead to situations in which certain regions of the country are over-represented in Parliament, while others have little to no representation at all.

In life and electoral systems: balance is key

It is for precisely this reason that I think the fear-mongering around how a PR electoral system would have given so many seats to the PPC is overblown. Sure, under a pure party-list PR system, they would have been entitled to something like 17 seats (leaving aside that voter behaviour would likely have been different under a different electoral system with different incentives). But nobody advocates for pure PR in Canada.

Every study, commission, citizen’s assembly or scholarly report on the question of reforming Canada’s electoral system (and there have been many) has advocated for some form of a mixed system: one that injects a moderate degree of party proportionality into the system, while retaining the important geographic dimension that is a hallmark of Canadian elections. Systems like Mixed-Member PR, Single-Transferable Vote, and others are designed to achieve precisely this balance- ensuring that voters still elect local representatives from their communities, but that parties are also fairly represented in the overall picture of the House of Commons.

What might that kind of system look like? It could entail the grouping of ridings into much larger, but still coherent, electoral districts, and then electing multiple MPs to each enlarged district on a proportional basis. To give you an example: take Toronto, where I live. Elections Canada has provided a handy breakdown of the vote totals in major urban centres. The Greater Toronto Area (as they’ve defined it) contains 53 ridings. In the 2021 election, all but five of them were won by Liberal candidates – a whopping 90.6% of the ridings (including every single riding in the City of Toronto!) But this landslide victory for the governing party masks a more complex reality: the Liberals only won 48.9% of the votes in the region. A full majority of voters in the region chose other parties, and yet the Liberals locked up nearly every riding. To paraphrase Henry Ford, in the GTA you can have any MP you like, as long as that MP is a Liberal.

What if, instead of 53 ridings each electing one MP, you had, say, 10 larger districts, and voters in each district elected five or six MPs? Each party could present a list of their five candidates in the district, and as a voter, you’d have the option of just voting for the party slate as a whole, or ticking an X next to your preferred candidate if you wanted to. When the votes were tallied, each party’s candidates would be elected on a reasonably proportional basis. Say the Liberal slate got 50% of the votes in one of the districts, they’d be entitled to three of the five or six seats in that district. The Conservatives might be entitled to two seats, with one seat for the NDP. Seats for each party would be filled in the order of candidates that the party established on the ballot, or based on voters’ preferences. The process would repeat for the other nine districts to elect the full slate of 53 MPs in the region, and likewise across the country.

What would this accomplish? Well for starters, voters in the GTA would have more diverse representation than the sea of Liberal red we’ve got right now. Each district would have moderately proportional results, but the regional dimension (i.e. the fact that there are still lines drawn around discrete electoral districts) would also ensure that every region of the country continued to elect MPs from their community. It would blunt the grotesque advantage that regionally focused parties currently have. And it would also effectively lower the bar for smaller parties to achieve representation: a small party wouldn’t need to have the most popular slate of candidates in the district, they’d just need to muster some 15-20% of the votes in the area to have a decent shot at one of the seats up for grabs.

It would also mean, importantly, that small fringe parties like the PPC would still have a tough time getting MPs elected. 5% of the votes probably wouldn’t be enough to get a candidate elected in a district with 5 or 6 seats available. They’d still need to focus resources on key areas where they could grow their support in order to win seats, but with a lower barrier to entry they might be able to squeak out a few wins. I think that is a small price to pay for a better, more responsive electoral system for everyone.

There are plenty of other ways you could design an electoral system to achieve proportional outcomes that respect regionality; the above example is merely to illustrate how PR could work in Canada without necessarily opening the floodgates to extremists. Fair Vote Canada has excellent resources for anyone interested in learning more about electoral reform.

The sudden rise of the People’s Party in this election has certainly given food for thought to electoral reformers as to the possible ramifications of a strictly proportional system. But at the end of the day, electoral systems ought to be designed to achieve fair and democratic outcomes – not to keep this or that particular party out of parliament. It remains true that proportionality is a key ingredient of any fair and just electoral system in a multi-party democracy, just as much as it remains true that local and regional representation are an important feature of Canada’s political culture. Real electoral reform that balances those priorities in equal measure, while moderating the excesses of both, is desperately needed in Canada- a truth that is in no way lessened by the existence of a far-right fringe party on our political landscape. If the PPC sticks around in its current toxic form for some time, well, that is a problem that Canadian society will have to reckon with one way or another. No electoral system can absolve us of that responsibility.