What does the withdrawal of the Frontier oil sands project have in common with the dismantling of Ontario windmills?

What does the withdrawal of the Frontier oil sands project have in common with the dismantling of Ontario windmills?

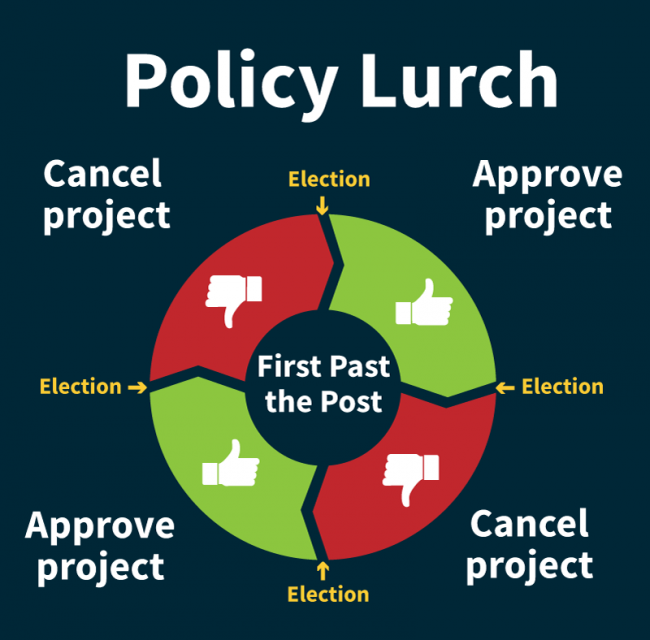

Both are victims of an unstable policy climate that ought to give any energy company a reason to think twice. Why would a company invest when today’s environmental regulations could change abruptly in less than four years? This kind of drastic policy lurch as one government is replaced by its opposite — and the uncertainty and instability it creates — is endemic to winner-take-all voting.

The letter from Teck Resources outlining the reasons for the abrupt withdrawal of their application for an oil sands project lays out the uncertainty:

The promise of Canada’s potential will not be realized until governments can reach agreement around how climate policy considerations will be addressed in the context of future responsible energy sector development. Without clarity on this critical question, the situation that has faced Frontier will be faced by future projects and it will be very difficult to attract future investment, either domestic or foreign.

While environmentalists celebrate the Teck decision as a victory in light of the urgent need to act on climate change, the same dynamic is playing out to their detriment in Ontario.

Since Doug Ford’s election to a majority in 2018 with 41% of the vote, Ontario’s PC government has cancelled 758 wind and solar projects, including White Pines Wind Farm, where the windmills literally had to be dismantled and hauled away. The Ford government cancelled rebates for electric vehicles – leading to a successful lawsuit against the government by Tesla. They cancelled funding to plant 50 million trees, leaving nursery owners in the lurch. The federal government stepped in to save the tree planting program for one year, but uncertainty for nurseries continues.

With winner-take-all voting, a small shift in the popular vote can mean a huge swing in power. For businesses whose products or services are supported or opposed by parties of different ideologies, first-past-the-post means the rug could be pulled out from under them because a few voters in a few swing ridings wanted to “throw the bums out.”

Research backs this up. Nooruddin’s study of economic volatility and electoral systems in 100 countries found that coalition governments produced less economic volatility due to more stable economic policy. He notes:

When a single party controls all the levers of the legislative process, it is better able to enact policies closer to its ideal point. The resulting policy might in fact be the preferred outcome for economic agents too (for instance, if the government in question favors a business-friendly policy regime), but the government can not guarantee that future governments will not reverse course should the opposition win. In this case, even if economic agents respond by investing in the country, they will remain wary of future policy change, and therefore forgo more irreversible investments.

Nooruddin also found that businesses judged countries run by coalitions to be more stable:

In a World Bank survey of firms across the world, I find that firms located in countries governed by parliamentary coalitions are less likely to perceive policy uncertainty to be a major obstacle to their businesses, and more likely to consider opening a new establishment in the near future.

Whether you support or oppose any particular project or business, the evidence is clear: the policy lurch of winner-take-all voting systems creates instability.

Companies hoping to invest in Canada’s energy future could be forgiven for wishing they had a crystal ball. The move to proportional representation could be key to a more stable and coherent climate and energy plan across the country–one that is supported by a true majority of Canadians.