Special Note: Since we wrote this Mythbuster below in 2014, we have published a Fact Checker with much more detailed research on stability and electoral system. If you’d also like to read the Fact Checker, click the button below!

Does Proportional Representation Mean Unstable Governments?

There’s hardly a mainstream media news article out there which doesn’t allude to this myth in some way – that making our votes count will supposedly lead to “instability.”

Sometimes the claims are extreme, coming close to suggesting that voter equality will plunge our country’s Parliament into permanent chaos.

Others are more moderate, claiming that there is some sort of “trade off” between democracy and stability: Sure, we can have better representation, but expect more unstable governments and frequent elections as the price.

These claims are 100% false.

Proportional systems are just as “stable.” There is no “trade-off”. We can have both: proportional representation and stable, effective governments.

Let’s dig a little deeper. When opponents claim that PR leads to “instability”, what do they mean?

Frequency of Elections

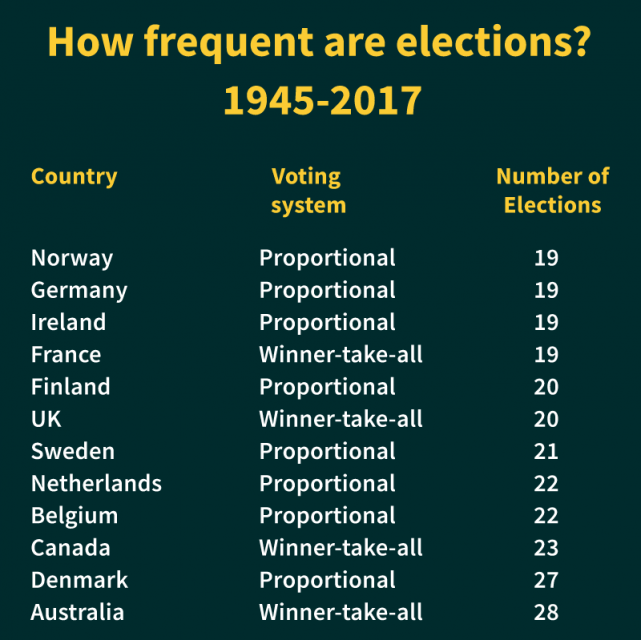

Contrary to the popular myth, among OECD countries using PR (our peers, of whom over 80% use proportional systems) elections are no more frequent than elections in Canada.

A study of countries over 50 years showed the average number of elections in countries using winner-take-all voting systems was 16.7 and in proportional systems it was 16.

But what about the exception – Italy? Of the 90+ countries which use proportional systems, opponents love to point to Italy. At one time, over 20 years ago, Italy used what people call a “pure” proportional system – a model unsuited for Canada which has never been proposed – and has changed its electoral system a number of times. Some of Italy’s more recent electoral systems were not even proportional – giving the party with the most votes bonus seats, to produce a manufactured majority. Italy now uses a semi-proportional, “parallel” voting system. Italy’s problems have persisted across every type of electoral system and are the product of a unique and problematic political culture. (Note: Between 1945 and today, Italy has had 18 general elections. The number in Canada over the same period is still greater at 23 elections).

Stable, Cooperative Governments Built on Positive Incentives

When many Canadians think of proportional representation, they imagine an endless string of minority governments.

Minority governments in Canada – parties working together for the common good – have produced some of the policies Canadians are most proud of, like universal health care. Esteemed political scientist Peter Russell’s “Two Cheers for Minority Government” celebrates this track record of minority government successes. In September, 2015, Russell wrote a letter signed by over 500 academics calling for proportional representation.

But we have also seen minority governments which were arguably dysfunctional, with little cross-party cooperation and a lot of partisan posturing, which ended in an early election.

What many people fail to understand is that winner-take-all behaviour is not the product of a minority government situation, it is the product of the incentives created by a winner-take-all system.

With a winner-take-all voting system, the primary goal of the parties is to secure their own single party majority government – 100% of the power, which they know they can achieve with under 40% of the vote. A minority government is seen by the larger parties as a temporary detour on the path to this objective.

In a first-past-the-post,minority government, the incentives for long term cooperation and finding common ground with other parties are weak. Instead, each party will attack its main “rivals” – even those whose policies are close to their own – hoping for the small shift in the polls which would suggest an advantageous time to trigger an election.

Policy Lurch/Policy effectiveness

When we talk about stability we need to look at how Governments function. An underlying problem with false majorities and any winner-take-all voting system is the need to go back and undo or fix the previous governments wrong-headed policy.

“Winner-take-all” electoral systems force parties to focus policy decisions on four-year cycles, with constant campaigning aimed at winning another 39 per cent majority. Long-term solutions on issues Canadians care about are sidelined in favour of inaction, pandering, or quick fixes that don’t always last. Stephen Harper spent his term undoing Liberal policy and infrastructure and in 2015, the Trudeau Government promised to rebuild what was lost: Canada Post, the long form census, pulling troops out of Syria, rebuilding our Coast Guard, unmuzzling scientists, rebuilding our criminal law system, restoring healthcare for refugees… you get the point.

These vast policy swings caused by switching between false majorities also causes instability in the investment sector, and create difficulties for long-term, business planning. If we were in a cycle of government where policy was a collaborative effort supported by a true majority we would be able to build policy that looked to the future. Governments would be able to build upon the last government, not undo the past at a massive cost to the taxpayer.

Consider that proportional countries, on average:

- Have lower income inequality – the more proportional the system, the lower the inequality, the more majoritarian the system, the higher the inequality

- Have higher scores on the Yale Environmental Index and more success at controlling carbon emissions and transitioning to renewables

- Have fewer deficits, more surpluses, and less debt

- Have higher scores on the UN Human Development Index, measuring quality of life – the social welfare of a country’s citizens

Why could this be? Canada has the same caring, intelligent, creative leaders, politicians and think tanks at our disposal. At least part of the answer lies with the ability of proportional voting systems to produce the cross-partisan cooperation and continuity needed to introduce changes that more people like, and make those policies last even when the government changes.

With proportional representation, the incentives are turned on their head.

When all the parties know that results of the next election will be proportional to the popular vote, a small change in the polls – leading to a small change in the seats – would make very little difference to the amount of power they each hold in Parliament.

A party which decides to be unnecessarily adversarial with a like-minded party in the House, or trigger an early election for the partisan advantage of possibly winning a few more seats, would be punished by the electorate.

Although it is still possible for a single party to win a majority of seats with a proportional system, most countries using PR are governed by stable, majority coalition governments, representing a genuine majority of voters.

As the data on election frequency shows, these coalitions are built to last.

Among the 80% of OECD countries with PR, minority governments are much less common than they are in Canada. Cooperation to ensure a lasting, productive government, and writing legislation together that reflects a broad set of values just makes more sense than trying to secure item-by-item approval for each bill. But with a new set of incentives that PR would bring, minority governments or more informal agreements between parties in Canada would very likely produce the same positive results.

Concluding Words about Proportional Representation and Stability

There is no evidence to support the assertion that proportional representation is associated with “instability”. Countries like Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, Scotland, Denmark and most of the OECD have been using proportional systems for decades. Opponents can always find one outlier country or case example in history to point to – but those same exceptions to the rule can be found among countries using winner-take-all systems.

The research evidence overall points to proportional representation producing stable, representative, cooperative governments with a strong track record of success on the issues most important to Canadians.

Reference: