Click here for an easy-to-print version of this document in Google Doc format.

Why Proportional Representation?

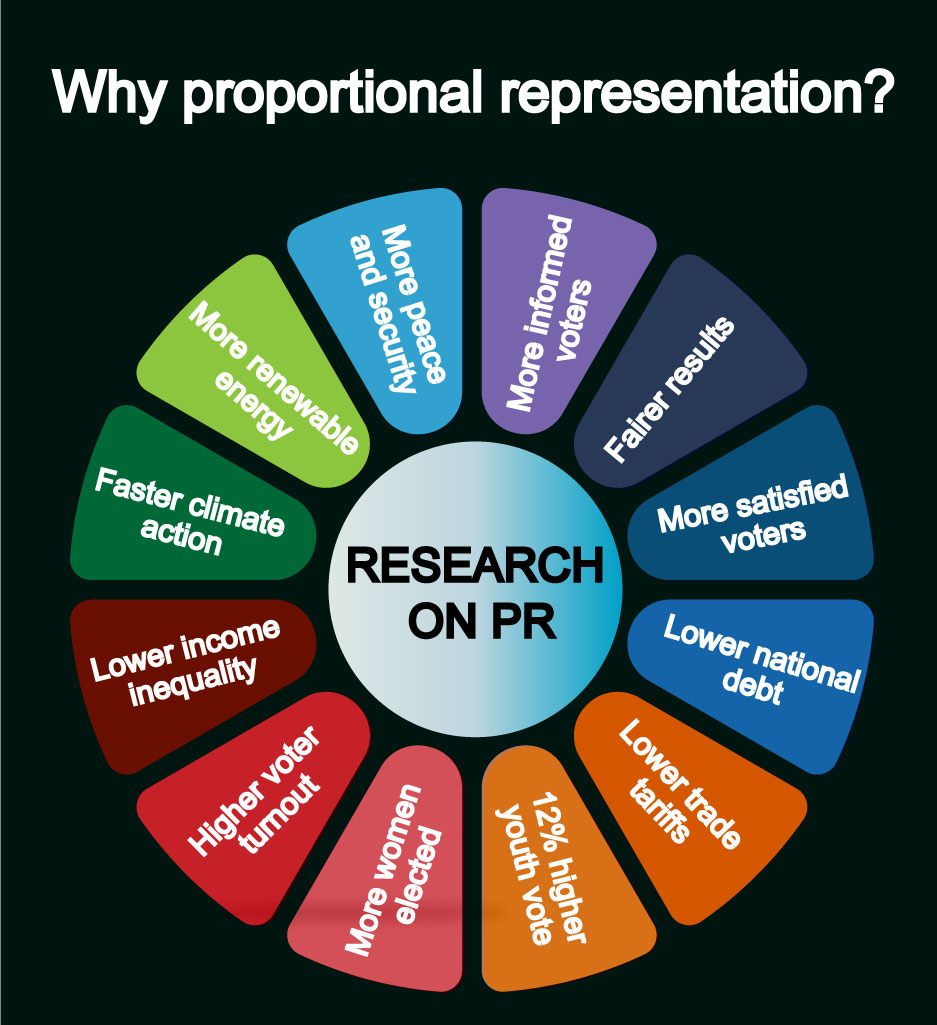

This document summarizes results from research comparing the performance of the two main families of voting systems: winner-take-all and proportional representation (PR). We already know that PR is a way of ensuring that all votes count and delivering more representative election results. The research cited below goes further, by demonstrating the impact of PR on the policy choices made by governments. This research shows that PR outperforms winner-take-all systems on measures of democracy, quality of life, income equality, environmental performance, and fiscal policy.

Comparing Winner-Take-All to Proportional Systems

Substantial comparative research has been conducted on the impact of winner-take-all systems vs proportional systems. This document covers a wide range of indicators, as one might expect, because the choice of electoral systems has wide ranging implications on how citizens relate to their governments and how government policies are considered and implemented.

Some reasons to expect a proportional system to have an impact:

- PR gives equal value to every vote and for this reason is likely to lead to increased government accountability to citizens and greater voter satisfaction. Some of the impacts of this can be seen below in the section titled Measures of Democracy.

- A flaw of winner-take-all systems is that small shifts in electoral preferences are sufficient to generate large shifts in power. This creates political instability and the phenomenon of “policy lurch” when one majority government is succeeded by another at the other end of the political spectrum. It also encourages political parties to jockey for short-term advantage rather than focusing on long-term policy issues. One can expect these tendencies to be reduced under PR, which fosters a long-term view and greater policy coherence over time.

- PR empowers ordinary citizens, by making every vote count and allowing for a wider range of views to be represented in the legislature. This can reduce inequality and improve access to social services over time, and, according to Salomon Orellana (2014), could have a salutary effect on how a country deals with diversity more generally. (Read a summary of his book here.) Orellana argues that increased opportunities for diversity and dissent allow PR countries to outperform in four areas:

- policy innovation

- mitigating the pandering of politicians in the pursuit of voters by promising quick-fix solutions

- increasing the political sophistication of the electorate

- limiting elite control over decision making.

Types of Electoral Systems

Political scientists classify electoral systems in different ways, and in fact every electoral system is unique in some respects. We use the expression “winner-take-all” to refer to electoral systems in which candidates are elected based on a plurality of votes received (more votes than any other candidate) or a majority of the vote—otherwise known as plurality/majoritarian systems. This includes most notably our own single-member plurality or first-past-the-post system, and systems like those used in France or Australia, which use run-off or instant runoff mechanisms to ensure that the winner enjoys majority support. Further complicating things are systems falling in between the two, of the sort we have in Spain, Italy and Greece, which are only semi-proportional.

Proportional systems are designed to ensure that the composition of the legislature reflects how citizens voted to the maximum extent possible.

Winner-take-all models are designed to maximize the probability of forming majority governments by a single party, whether that party achieves a majority of the vote or not.

Measures of Democracy

Arend Lijphart, a world-renowned political scientist, spent his career studying various features of democratic life in different countries. In his landmark study (2012), he compared 36 democracies over 55 years. Lijphart uses his own classification system, speaking of “majoritarian” and “consensual” democracies. We will call these “winner-take-all” and PR countries.

Using World Governance Indicators and Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, Lijphart found that PR countries outperformed winner-take-all ones on 16 out of 17 measures of sound government and decision making – nine of them at a statistically significant level – including government effectiveness (quality and independence of the public service, quality of policy making), rule of law, and the level and control of corruption (including capture of the state by elite interests).

Looking at a number of specific indicators, Lijphart found that in countries using proportional systems:

- Voter turnout was higher by 7.5 percentage points, when contextual factors are taken into account.

- Government policies were closer to the view of the median voter.

- Citizens were more satisfied with the performance of their countries’ democratic institutions,

even when the party they voted for was not in power. - There was a small increase in the number of parties in Parliament.

- The share of women elected to legislators was 8 percentage points higher.

- Scores were higher on measures of political participation and civil liberties

Lijphart concludes that consensual (PR) democracies are “kinder, gentler democracies.”

Research by other authors has yielded similar results. Lijphart’s finding that proportional systems lead to governments that better reflect the views of the median voter was confirmed by McDonald, Mendes and Budge (2004), who looked at 254 elections producing 471 governments in 20 countries.

Blais and Loewen (2007) found that citizens in countries with PR were more satisfied with their democracy and that elected officials were more responsive to the electorate. Blais, Morin-chassé and Singh (2017) found that citizens are “sensitive to deficits in representation” and that satisfaction with democracy is lower when the party one voted for does not get seats in proportion to the popular vote.

Pilon (2007) demurs somewhat on the subject of PR’s impact on voter turnout, noting that the observed impact varies from study to study and is affected by other considerations than the choice of electoral system, but ends up supporting Lijphart’s conclusion, describing the “typical bonus” of voter turnout under PR to be in the order of seven to eight percentage points.

Research by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance examining youth participation in elections in 15 countries suggests that the boost in turnout in proportional systems may be as much as 12 percentage points higher for youth (85.8% in the presence of high proportionality vs. 73.9% in its absence) (IDEA 1999: 30).

Proportional representation may also be associated with higher levels of political knowledge among citizens. Gordon and Segura (1997) conclude that:

Seats-votes disparities are a disincentive to interest in politics since accumulated preferences are not directly reflected in the composition of representative institutions.

Milner (2014) adds that parties under proportional systems are more consistent over time, making it easier for citizens to decide which party or parties best reflect their political preferences. He argues that parties tend to change their platforms and leaders more often under first-past-the-post in an attempt to generate minor shifts in short-term voter preferences that can translate into much larger shifts in the number of seats won. Since PR systems do not inflate the effect of shifting voter preferences in the same way, parties under PR prefer to build up adherents over the long term rather than shifting their policies and leaders in response to short-term opportunities.

PR systems thus provide voters with relatively clear and stable “political map” over time. “In this way,” Milner summarizes, “PR fosters political knowledge and thus,potentially, electoral participation, especially at the lower end of the education ladders, where information about issues and actors is at a premium.”

Women in politics

There exists an abundance of research on the effects of electoral systems on the participation of women in politics. As we saw above, Lijphart found that the share of women in parliamentary bodies was eight percentage points higher in PR countries. This finding of a positive correlation between PR and women elected to legislatures is well established in the literature (Norris 2004).

While women’s participation in politics can only be explained with reference to a wide range of variables, the research community is united in declaring that PR elects more women. One of the most widely accepted theories is that multi-member districts allow more women to be elected because parties will want to put forward a diversified slate of candidates to reach a wider range of voters. It is much easier for a party to ensure balanced representation with multi-member districts than in single-member districts.

Australia provides the perfect petri dish to test this theory, because the two houses of parliament use different electoral systems to elect their Representatives: a winner-take-all system with preferential ballots in single-member ridings called the Alternative Vote (AV) for the House of Representatives, and a proportional system called the Single Transferable Vote (STV) for the Senate.

The results are what the theory would predict. Kaminsky and White (2007) looked at elections in both chambers over a 61 year period and found that more than two and a half times more women were elected to the Senate than to the House of Representatives. After women were given the right to run for Parliament in 1902, the share of women representatives began to increase sooner in the Senate than in the House, and has averaged 10-15 points higher in recent years (37% vs. 26% in 2013).

Canada, the US and the UK vote with plurality systems, while France and Australia’s lower house vote with majoritarian systems, and all share an embarrassingly low rate of women in their legislatures. None reach or exceed the most basic target set by the United Nations of 30% representation of women in politics. In comparison, legislatures in PR countries such as New Zealand, Germany, Sweden,and Denmark all include over 30% women. Sweden tops the chart at 45%.

In Canada, more women are running for office (533 in 2015), yet only 16.5% of those women were elected. Women’s representation in Canada’s House of Commons is stuck at only 26%.

Stability and Ability to Take a Long-term Perspective

One of the biggest debates about PR is whether it leads to political and policy instability. This section looks at several facets of this question:

- the frequency of elections,

- the issue of policy lurch, and

- the ability of governments to deal with long-term issues of importance to the economic and environmental stability of the country.

As we shall see, the evidence strongly favours PR over winner-take-all systems.

Frequency of elections

Regarding the frequency of elections, the comparative research shows little difference between PR and FPTP countries. Looking at elections from 1945 to 1998, Pilon (2007: 146-154) calculates that countries using FPTP averaged 16.7 elections, while countries using proportional systems averaged only 16.0 elections. The difference between these two groups of countries is negligible.

Pilon points to other data that shows a somewhat shorter government life-span in PR countries (1.8 years as opposed to 2.5 years in FPTP countries), but discounts this result because it is heavily influenced by Italian experience mainly involving what would elsewhere only be considered as cabinet shuffles (2007: 147). He concludes that this type of instability is “not a problem for PR systems in western countries” (2007: 151).

Policy lurch

However, there are other ways to assess the link between electoral systems and stability. Countries with winner-take-all systems that tend to oscillate from left to right, are characterized by policy shifts largely unrelated to underlying voter preferences, and cannot be said to satisfy the test of stability terribly well. Indeed, it is not unusual for one government to simply undo what the previous government has done, in a process of “policy lurch” in winner-take-all systems such as Australia, the US, the UK and Canada.

In New Zealand, dramatic policy shifts enacted by the National and Labour governments in the 1970s and 1980s were one of the main reasons for voter disaffection with the first-past-the-post system prior to the introduction of MMP in 1996. Although the government has continued to be dominated by the National and Labour parties at different moments since then, the need of the government to secure the support of other parties to enact legislation and the stronger voice of smaller parties in the House are felt to have considerably tempered the policy lurch phenomenon (Shaw 2016).

In Canada, we need look no further than the efforts by the Harper government to undo much of the Liberal government legacy that they inherited and the subsequent undoing of conservative policies by the Liberal government following the 2015 election.

After the Liberal Government came to power in 2015, they published a list of budget cuts enacted by the previous government, many of which were aimed at programs established by previous Liberal governments.

This included cuts to:

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development,

- the Environment Portfolio,

- Fisheries and Oceans,

- Parks Canada Agency,

- CBC,

- Citizenship and Immigration,

- the Canadian Food Inspection Agency,

- the Canadian Heritage Portfolio,

- Library and Archives Canada,

- the National Arts Centre, and

- the National Film Board of Canada.

The Liberal Government elected in 2015 then spent much of its first year in office undoing these cuts, including the following measures (Various media reports, 2015/2016):

- restored the long-form census;

- pledged to reverse funding cuts to the CBC;

- overturned the closing of veterans offices;

- overturned two pieces of legislation it considered punitive to labour;

- restored funding to First Nations which had been frozen under the previous government’s transparency act;

- planning to boost Parks Canada to counter Tory budget cuts;

- reopened coast guard stations;

- reopened funding for women’s groups;

- restored refugee health benefits cut by previous government…

Such policy shifts are a normal feature of our electoral system because small shifts in the political winds and lead to significant shifts in power, as the country goes from a majority government at one pole of the spectrum to another.

Economic Performance and Fiscal Responsibility

That sensitivity of winner-take-all systems to small shifts in voter preferences has another well known implication: the tendency of politicians to focus on short-term issues or wedge issues at the expense of long-term policy issues. This subsection and the following one suggest that PR systems are better equipped to deal with long term issues such as sound fiscal management, economic growth and environmental management.

Commenting on the economic performance of countries using different systems, Carey and Hix (2009 and 2011) found that countries with moderately proportional systems were more fiscally responsible and more likely to enjoy fiscal surpluses. Orellana (2014) has also found that proportional systems tend to have higher surpluses or lower deficits than less proportional systems, and lower levels of national debt. Orellana’s regression analysis predicts a surplus of 0.05 percent of GDP for fully proportional countries, against a deficit of 2.9 percent of GDP in winner-take-all countries. The projected national debt is 65.7 percent higher in winner-take-all countries than in those with fully proportional systems, meaning the cost of servicing the debt will be higher.

Turning to the issue of economic performance more generally, the correlation seems to depend upon the sample being used. Lijphart and Orellana found no relationship between electoral systems and economic growth. However, when Knutsen (2011) looked at a much longer historical period involving 3,710 country-years of data covering 107 countries from 1820 to 2002, he found that proportional and semi-proportional systems produced an “astonishingly robust” and “quite substantial” increase in economic growth – a one percentage point increase – compared to winner-take-all systems. Knutsen suggests that this may be because PR tends to promote broad-interest policies rather than special interest policies; and because PR systems produce more stable and thus more credible economic policies. He concludes that PR and semi-PR systems generate more prosperity than winner-take-all systems.

In fact, 9/10 of the top economic performers in the OECD with the highest GDP per capita use proportional representation.

Alfano and Baraldi (2015) studied 91 countries from 1979–2010 and found a non-linear relationship between proportionality and rates of growth. The relationship appeared as a curve with the growth rate reaching its maximum value in correspondence with an intermediate degree of proportionality, corresponding to a Gallagher index about equal to 6.5. Remarkably, the predicted growth rate for highly disproportional systems drops sharply into negative territory for a Gallagher index above about 14. They explain these results by suggesting that:

in systems with an intermediate degree of proportionality, the beneficial accountability characteristics of plurality/majoritarian systems (which may induce office-motivated politicians to enact growth-promoting policies) are put beside the beneficial representativeness characteristics of PR (which induce politicians to enact public policies that benefit broad rather than narrow interests). Secondly, a mixed method enhances both political and government stability stimulating a relatively high growth rate.

This backs up the findings of Carey and Hix (2010, London School of Economics) that there is an “electoral sweet spot” where moderately proportional systems outperform both winner-take-all systems and extremely proportional systems.

Opponents of proportional representation sometimes suggest that making votes count is “bad for business” because businesses will be overtaxed and investors will flee. However, the average corporate tax rate in PR countries was actually lower in 2017: 22.9% for PR countries vs. 27.2% for winner-take-all countries.

Looking at trade protection, which economists usually decry as being bad for the economy, in a study of 147 countries over 23 years, Evans (2009) found that winner-take-all systems have higher tariffs than proportional systems.

The overall impact of electoral systems on the economy is a complicated topic on which further research is being done, but there is no reason to fear the economic implications of bringing PR to Canada.

Click here to access Fair Vote Canada’s mythbuster on this issue.

Environmental Stewardship

Frederiksson and Millimet (2004) found that countries with proportional systems set stricter environmental policies. Cohen (2010) found that countries with proportional systems were faster to ratify the Kyoto protocol, and that their share of world total carbon emissions had declined.

Lijphart (2012) found that countries with proportional systems scored six points higher on the Yale Environmental Performance Index, which measures ten policy areas, including environmental health, air quality, resource management, biodiversity and habitat, forestry, fisheries, agriculture and climate change.

Using data from the International Energy Agency, Orellana (2014) found that between 1990 and 2007, when carbon emissions were rising everywhere, the statistically predicted increase was significantly lower in countries with fully proportional systems, at 9.5%, compared to 45.5% in countries using winner-take-all systems.

Orellana also found that citizens in countries with proportional representation were more supportive of environmental action, and more willing to pay the costs associated with environmental protection. He found the use of renewable energy to be approximately 117 percent higher in countries with fully proportional electoral systems.

In sum, countries with proportional systems tend to act more quickly and do more to protect the environment.

Social Policy

As noted earlier, PR tends to empower ordinary citizens and one might expect that to be reflected in indicators of income inequality and of social policy outcomes. This expectation is borne out by the research.

Income Inequality and Representation of Lower Income Citizens

Lijphart (2012: 282) found that countries with proportional systems had considerably lower levels of income inequality.

Likewise, Birchfield and Crepaz (1998:192) found that “consensual political institutions [which use PR] tend to reduce income inequalities whereas majoritarian institutions have the opposite effect.” The results of the regression work they present were highly significant, with PR accounting for 51% of the variance in income inequality among countries. Birchfield and Crepaz explain this result in terms of the higher degree of political power of people in PR systems. In their words (1998:191):

The more widespread the access to political institutions, and the more representative the political system, the more citizens will take part in the political process to change it in their favour which will manifest itself, among other things, in lower income inequality. Such consensual political institutions make the government more responsive to the demands of a wider range of citizens.

Vincenzo Verardi, in a study of 28 democracies (2005), also found that when proportionality increases, inequality decreases. Iversen and Soskice (2006) found that PR is associated with greater efforts to promote income redistribution.

Bernauer, Giger and Rosset (2015) looking at 24 Parliamentary democracies, found that the political preferences of low income citizens are better represented in a more proportional system, and the political preferences of the rich are better represented in a winner-take-all system.

Human Development

Investigating the broader impact of PR on society, Carey and Hix (2009 and 2011) looked at 610 elections over 60 years in 81 countries and found that PR countries garnered higher scores on the United Nations Index of Human Development, which incorporates health, education and standard of living indicators. Carey and Hix consider that the Index of Human Development provides “a reasonable overall indicator of government performance in the delivery of public goods and human welfare.” Lijphart found that countries with PR spent an average of 4.75% more on social expenditures than winner-take-all democracies.

Patterson (2017) studied the experience of 179 countries with different types of democratic or autocratic regimes between 1975 and 2012 and found that countries with proportional systems outperformed countries with closed aristocracies on population health. Countries with PR had up to 12 more years of life expectancy on average and 75% less infant mortality, and lower mortality rates for most other age groups. Shockingly, improvements in population health over time in countries with winner-take-all systems were not better than they were in closed autocracies. The authors conclude that electoral rules that in some way support broad representation appear to be more conducive to positive health outcomes than even democracies.

Looking at 21 OECD countries between 1981 and 2008, Altman, Flavin and Radcliff (2017) found robust evidence that citizens in countries with proportional representation reported higher levels of life satisfaction, concluding that the real-world consequences for human well-being of PR and other features of democratic rule are substantial compared to other common predictors.

Diversity and Social Cohesion

Electoral systems can affect how citizens and government interact and how citizens relate to each other. As we saw in the introduction, Orellana provides a number of reasons why the diversity of views in PR systems can have an impact. Here are some of the repercussions of adopting more proportional electoral systems.

Prejudice, Tolerance and Changing Attitudes

Using data from the World Values Survey conducted between 1981 and 2010, Orellana found that citizens in countries with proportional systems tend to show less prejudice towards minority and marginalized groups. Countries with winner-take-all systems scored approximately 44 percent higher on the prejudice scale than countries with fully proportional electoral systems.

He found that citizens in countries with more proportional electoral systems tend to have higher levels of tolerance for homosexuality, abortion, divorce, euthanasia and prostitution; and a higher level of disagreement with the notion that men make better leaders.

Furthermore, their attitudes towards those issues tended to evolve more quickly than elsewhere. Over a roughly 25-year period, the share of the population demonstrating tolerance of homosexuality increased by 41 percentage points in countries using proportional systems but only 20 percentage points in single member district systems.

Law Enforcement and National Defence

Perhaps because PR mitigates pandering for votes based on quick fixes, both Lijphart and Orellana found that countries with less proportional systems tend to have more public support for punitive solutions to crime, and produce more punitive policy outcomes including higher incarceration rates and greater use of capital punishment. Orellana found that support for incarceration is approximately 28 percentage points higher in countries with winner-take-all systems. Confirming similar results by Lijphart, he found that the statistically-predicted incarceration rate for countries with fully proportional systems was 136 per 100,000 people compared to 246 per 100,000 in winner-take-all countries.

Relying on an indicator of privacy and surveillance produced by Privacy International for over 30 countries, Orellana found that countries with proportional systems scored 58% higher on the privacy index.

Looking at the average military expenditure as a percentage of GDP between 1988 and 2012 and data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Orellana found that the predicted level of military spending for countries with winner-take-all systems was more than twice as high as for countries with fully proportional systems (2.6% vs. 1.1% of GDP).

Leblang and Chan (2003) found that a country’s electoral system is the most important predictor of a country’s involvement in war, according to three different measures: (1) when a country was the first to enter a war; (2) when it joined a multinational coalition in an ongoing war; and (3) how long it stayed in a war after becoming a party to it.

Lijphart found that PR is strongly correlated with a lower degree of violent events, more political stability and a lower risk of internal conflict. Qvortrup and Lijphart (2013), looking at the same 36 countries studied in Lijphart’s earlier work, found “statistically significant correlations between the index of consensus democracy and a higher incidence of fatal domestic terror incidents in the period 1985–2010.” They also found that the risk of fatal terrorist attacks was almost six times higher in winner-take-all democracies.

Is perfect proportionality needed to have an impact?

One might wonder how perfectly proportional an electoral system has to be before its impact is felt. This is relevant to Canada, which is considering MMP and other regionally-based options that are highly, but not fully, proportional.

The issue was the primary research question covered by Carey and Hix. Their results show that moderately proportional systems involving multi-member districts of six to eight seats made it possible to avoid disproportional results to a degree almost matching that of more purely proportional systems (2011: Figure 3). They point to countries such as Costa Rica, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain that have settled for a moderate degree of proportionality in the design of their electoral systems.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the existing body of comparative research internationally leaves little room for doubt that PR is the better choice.

PR outperforms winner-take-all systems in almost every respect:

- higher quality of democratic life,

- prudent fiscal management,

- higher economic growth,

- better environmental management,

- reduced income inequality,

- higher levels of human development,

- greater tolerance of diversity,

- a less punitive approach to law enforcement,

- greater respect for privacy, and

- lower levels of conflict and militarism.

References

ACE Electoral Knowledge Network (updated regularly online). Encyclopaedia on Electoral Systems.

Alfano, M. & Baraldi, A. (2015). Proportional Degree of Electoral Systems Growth: A Panel Test. Rev. Law Econ. 2015; 11(1): 51–78

Altman, A, Flavin, Flavin, P. and Radcliff, B. “Democratic Institutions and Subjective Well Being.” Political Studies 2017, Vol. 65(3) 685–704.

Bernauer, Giger and Rosset (2015). “Mind the gap: Do proportional electoral systems foster a more equal representation of men and women, poor and rich?”International Political Science Review. 36-1: 78-98.

Birchfield, Vicki and Crepaz, Markus (1998). “The Impact of Constitutional Structures and Collective and Competitive Veto Points on Income Inequality in Industrialized Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 34: 175-200.

Blais, A, Loewen, PJ (2007). “Electoral systems and evaluations of democracy.” In: Cross, W (ed.) Democratic Reform in New Brunswick. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press, pp. 39–57.

Blais, Morin-chassé and Singh (2017). “Election outcomes, legislative representation and satisfaction with democracy.” Party Politics. Volume: 23 issue: 2, page(s): 85-95.

Carey, John M. and Hix, Simon (2009). “The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems. PSPE Working Paper 01-2009. Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Carey, John M. and Hix, Simon (2011). “The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems.” American Journal of Political Science 55-2: 383-397.

Cohen, Darcie (2010). Do Political Preconditions Affect Environmental Outcomes? Exploring the Linkages Between Proportional Representation, Green parties and the Kyoto Protocol. Simon Fraser University.

Evans, C. L. (2009). “A protectionist bias in majoritarian politics: An empirical investigation.” Economics & Politics, 21-22: 278–307.

Fredriksson, P. G. and Millimet, D. L. (2004). “Electoral rules and environmental policy.” Economics Letters, 84-2: 237–44.

Gordon, S. B., & Segura, G. M. (1997). “Cross-national variation in the political sophistication of individuals: capability or choice?” Journal of Politics, 59-1: 126–47.

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA, 1999). Youth Voter Participation.

Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2006). “Electoral Systems and the Politics of Coalitions: Why Some Democracies Redistribute More Than Others. American Political Science Review 100-2: 165–81.

Kaminsky, J., & White, T.J. (2007). Electoral systems and women’s representation in Australia. Commonwealth and Comparative Politics 45: 185-201.

Knutsen, Carl (2011). “Which Democracies Prosper? Electoral Rules, Forms of Government, and Economic Growth.” Electoral Studies 30: 83-90.

Leblang, D., & Chan, S. (2003). “Explaining Wars Fought By Established Democracies: Do Institutional Constraints Matter?” Political Research Quarterly 56-24: 385–400.

Lijphart, Arend (2012). Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in 36 Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale Press. Fair Vote Canada has produced a summary of the 1999 edition.

McDonald, M., Mendes, S. and Budge, I. (2004). “What are Elections for? Conferring the Median Mandate.” British Journal of Political Science 34: 1-26, Cambridge University Press.

Milner, H. (2014). How does proportional representation boost turnout: a political knowledge based explanation.

Norris, P. (2004) Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa (2011). Making Democratic-Governance Work: The Consequences for Prosperity. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP11-035, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Orellana, Saloman (2014). Electoral Systems and Governance: How Diversity Can Improve Policy Making. New York: Routledge Press. Click here for a summary produced by FVC.

Patterson, A. (2017). Not all built the same? A comparative study of electoral systems and population health. Health and Place 47: 90-96.

Pilon, Dennis (2007). The Politics of Voting: Reforming Canada’s Electoral System. Toronto: Emond Montgomery.

Qvortrup, M., & Lijphart, A. (2013). Domestic terrorism and democratic regime types. Civil Wars, 15-4: 471–485.

Rule, W. (1994). “Women’s under-representation and electoral systems.” Political Science and Politic, 27: 689-692.

Rule, W., & Zimmerman, J.F. (1994). Electoral systems in comparative perspective: Their impact on women and minorities. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Shaw, James (2016). Presentation at the Green Party of Canada Convention, Ottawa, August 5-7, 2016 and associated discussion.

Various media reports (2015/2016). “Burning down the Harper legacy serving Trudeau well,” Thestar.com; “Carolyn Bennett reinstates funds frozen under First Nations Financial Transparency Act,” CBC News; “Environment Minister seeks to boost Parks Canada after nearly $30 million in Tory budget cuts,” CBC News; “Fisheries minister in Vancouver to help re-open Kitsilano Coast Guard,” National Observer; “Liberals to reopen funding taps for women’s groups,” Thestar.com; “Liberals restore refugee health benefits cut by previous government,” The Globe and Mail.

Verardi, Vincenzo (January 2005). ”Electoral Systems and Income Inequality.” Economics Letters, 86-1: 7-12.